Long-awaited homecoming signals new era for Philadelphia Housing Authority

Listen

The Queen Lane Apartments open in Germantown (Bastiaan Slabbers/for NewsWorks)

Under a white tent on Priscilla Street this week, residents and elected officials joined Philadelphia Housing Authority brass to celebrate the start of a new chapter.

Last September, a tiny bit of explosives razed Queen Lane Apartments, a 60-year-old high-rise with a history of drugs and violence. In its place, now stands a brand-new set of townhomes people think could help kick-start a “revolution” in Germantown.

“This is such an improvement in the neighborhood,” said longtime resident Corliss Gray near two stacks of purple and blue balloons. “I think it’ll bring people in who will do better for the neighborhood.”

The new $22 million development, however, left Philadelphia with fewer affordable apartments, a not-so-small side effect in the country’s biggest poor city.

After 119 units went down, just 55 went up.

Over the past two decades, while demolishing 24 high-rise buildings across the city, PHA has lost 7,000 units.

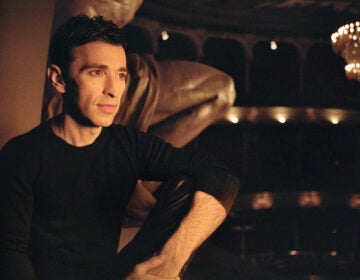

Philadelphia Housing Authority President Kelvin Jeremiah. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

Philadelphia Housing Authority President Kelvin Jeremiah. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

It’s a figure that PHA President Kelvin Jeremiah can recite from memory. And one he refuses to boost.

And so, the new Queen Lane Apartments represents the last time PHA implodes a high-rise and doesn’t replace every unit during redevelopment.

“I don’t believe it’s in the public interest to continue to increase the exodus of affordable housing units. The demand hasn’t shrunk any,” said Jeremiah in an interview.

A 20-year wait

The authority’s waiting list has had roughly 100,000 names on it for years. On average, it’s taking people 10 years to get a unit.

Karen Collins has been waiting for 20.

Karen Collins sits on the porch of her Section 8 home in West Philadelphia. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

Karen Collins sits on the porch of her Section 8 home in West Philadelphia. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

She lives with her two kids in a row home not far from the zoo in West Philadelphia. It’s Section 8 housing, meaning her rent is heavily subsidized. Collins pays about $200 a month for a unit that could otherwise fetch $800 or more.

But unlike most residing in PHA units, Collins has to cover utilities, a difficult task considering she’s physically disabled – nerve damage – and survives on Social Security.

“My income comes in the door, it goes right back out that door. But I’m a saving personality. Ten cent here, $10 there, that’s how we make it,” said Collins.

The long wait has also taken a heavy physical and emotional toll. There’s no wheelchair ramp outside Collins’ house or any modifications inside.

Karen Collins says the house is not ideal because of her disability. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

Karen Collins says the house is not ideal because of her disability. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

“I’m wearing myself out,” she said. “One day, I’ll be able to walk. The next day I may not be able to walk. That makes me angry.”

Depressed sometimes, too.

“PHA is a godsend that’s under attack, but they’re also one of our worst nightmares,” said Collins.

Others have benefited from PHA tearing down its high-rises, though. Inez Green is among them.

In 1984, Green moved into a high-rise unit at the Southwark Housing Development at Fourth Street and Washington Avenue in South Philadelphia.

Inez Green is resident council president of the Courtyard Apartments, which replaced the Southwark Towers. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

Inez Green is resident council president of the Courtyard Apartments, which replaced the Southwark Towers. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

She said the apartments were fine. The rest of the building was a nightmare.

Bad lighting.

Broken elevators.

Drug deals in the stairwells.

“It was horrible,” said Green. “It was really bad.”

The streets outside the tower weren’t much better.

“It was really violent. You couldn’t go out sometimes. People would come around saying, ‘Well, we’re getting ready to do this — like fight or shoot or whatever. Take your kids in,'” said Green.

Green said things slowly starting getting better after 2000, the year PHA tore down two of the three towers at Southwark. It replaced them with two-story buildings with postage-stamp sized lawns out front.

One tower remains of the Southwark housing development in South Philadelphia. Two were torn down and replaced by two-story buildings. The development is now called the Courtyard at Riverview. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

One tower remains of the Southwark housing development in South Philadelphia. Two were torn down and replaced by two-story buildings. The development is now called the Courtyard at Riverview. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

The homes and a remaining tower are now collectively part of the Courtyard at Riverview.

Green said there’s still crime, but it’s less rampant and that there’s a better relationship with residents in nearby Queen Village, now one of the city’s most desirable neighborhoods.

“It went from project to development,” said Green. When kids say, ‘You’re in the projects,’ no you’re in the development, cause a project is something that’s not done. This is complete. So we changed their mindset so they could move on and let them know that they’re better than what people portray them to be.”

For now, PHA still has 16 towers comprising 1,760 units.

They cover eight locations, including:

Norman Blumberg Apartments

Courtyard at Riverview

Emlen Arms

Fairhill Apartments

Germantown House

Harrison Plaza

Westpark Apartments

Wilson Park

Looking for land — and more funds

Nearly half of those properties are dedicated to seniors and, “more than likely,” won’t be demolished, said Jeremiah.

The rest, “family buildings,” could be torn down in the coming years, though there’s no way to know how much federal funding will be available down the line.

For now, PHA has plans to demolish only two towers at Norman Blumberg Apartments in the Sharswood section of North Philadelphia. The implosion is part of a $500 million plan aimed at completely transforming the struggling neighborhood.

Jeremiah said his agency alone can’t solve what he calls a housing crisis, but he’s willing to try. To him, everything starts at home.

“We know that you can’t get a job if you’re transient. We know that you can’t be in a stable school if you don’t have stable housing,” said Jeremiah. “So first let’s deal with the housing situation. Let’s stabilize our families, because at that point we can provide them the services that they need.”

Replacing each and every unit when imploding a tower means PHA will need to find more land and funding, two big question marks in need of answers if the agency wants to add more ribbon-cutting ceremonies to the calendar — rather than people to its waiting lists.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.