How a Philadelphia outbreak of Legionnaires’ disease in 1976 led to modern-day investigations and surveillance

Legionnaires’ disease was named after a large outbreak in Philadelphia sickened hundreds of American Legion veterans in the summer of 1976.

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

Cases of Legionnaires’ disease have been generally on the rise for the last 50 years, ever since the disease was first identified and named after an outbreak in Philadelphia during the summer of 1976.

New York City just recently saw 114 cases, which included 90 hospitalizations and seven deaths in the Central Harlem area. The responsible bacteria were found in air conditioning cooling towers at a local hospital and at a nearby construction site, and health officials have now declared this outbreak as officially over.

Experts say Legionella pneumophila, the bacteria that causes the illness, isn’t any more dangerous today than it was back in 1976. But they warn that humans as hosts have perhaps become more susceptible to the disease over time.

“We have dirtier air, we have a warming climate, we have people with chronic conditions,” said Dr. René Najera, director of public health at the College of Physicians of Philadelphia. “And in a warming climate, that leads to more air conditioning, which leads to more exposures, right? So, it’s this cycle that unfortunately is not just for Legionnaires’, but for other bacteria and viruses, it’s expanding.”

How a Philadelphia convention led to a mysterious illness among Pennsylvania veterans

Finding the cause of Legionnaires’ disease almost 50 years ago took a massive effort by scientists and public health officials. They banded together from all levels of government, launching one of the largest disease investigations in U.S. history to solve a medical mystery.

The summer of 1976 was a time of many celebrations in Philadelphia. The city was entertaining visitors for the bicentennial anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence and the country’s birth.

That July, Pennsylvania members of the American Legion gathered for a convention at the iconic Bellevue-Stratford Hotel on Broad Street. About 2,000 veterans came in from all over the state for the four-day event.

Within days of returning home, some of the veterans developed pneumonia and fatal respiratory infections.

These events took place before Najera was even born, but he later learned that a colleague’s father was among the affected veterans.

“Her father came back on Friday from the convention and by Sunday, he was in the hospital and by Monday or Tuesday he was dead,” he said.

Public health experts were alarmed and puzzled. They soon found a connection between the sick veterans and the recent American Legion conference in Philadelphia.

“It was very clear that people who had been at the Bellevue had contracted this and they were all getting very, very sick,” Najera said.

They also found that a small number of other people who had not attended the conference, but had walked by the hotel on the street during that same week, were also infected.

Investigators could not figure out the root cause and why the mysterious illness only affected people who had been inside or near the hotel on specific days. They ruled out viral infectious diseases like influenza, which easily passes from person to person.

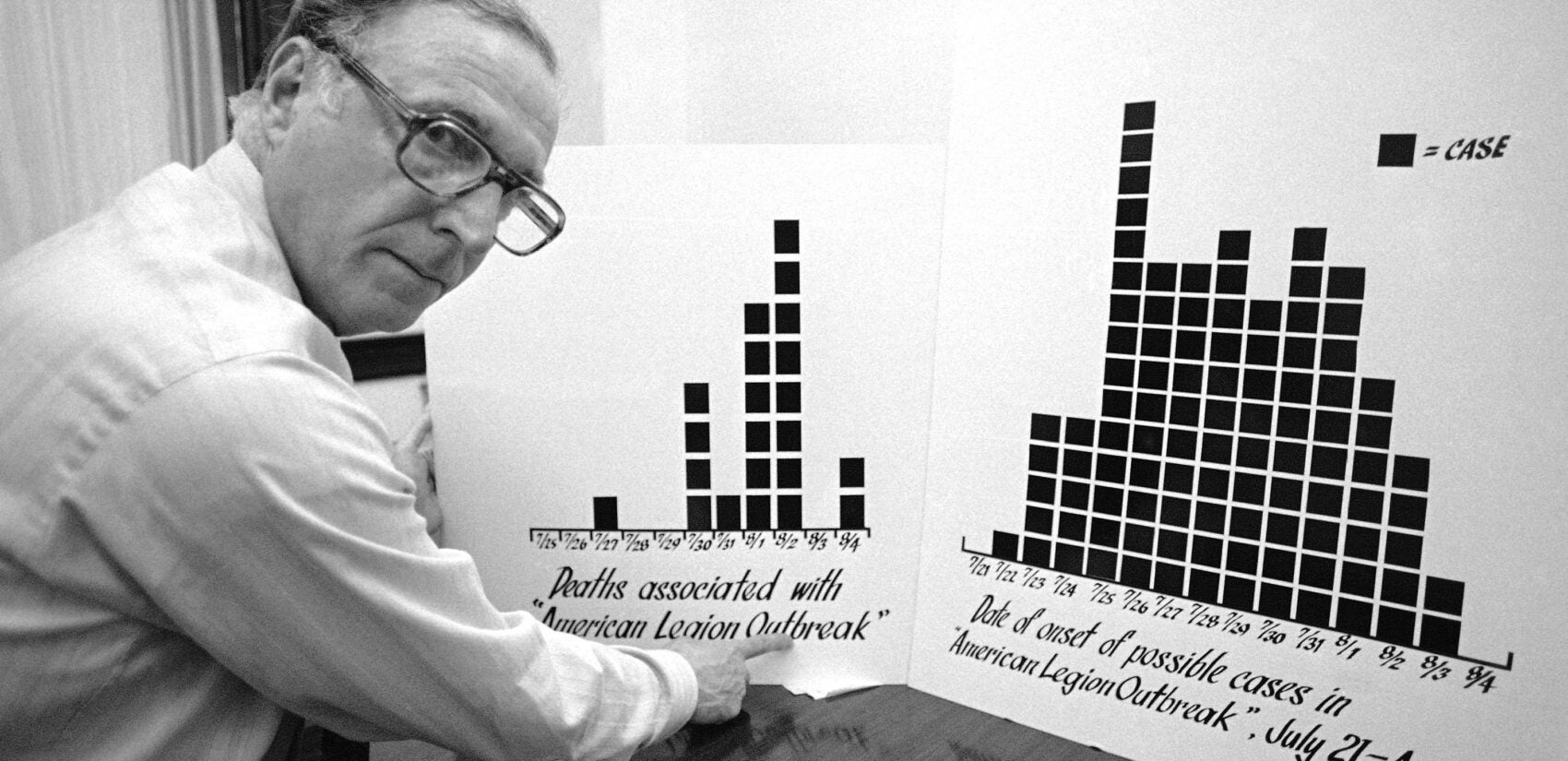

Meanwhile, the death toll from this mysterious illness was rising. By mid-August, 29 people had died and 200 were hospitalized. The outbreak was being heavily covered by the national media.

Eventually, people just stopped coming to Philadelphia, said epidemiologist Dr. Robert Sharrar.

“There were no lines at the Liberty Bell in August,” he said. “There was still the unknown, scary phenomenon.”

Sharrar is a fellow at the College of Physicians of Philadelphia. But in 1976, he led the city’s communicable disease program at the Department of Public Health.

It was the media, he said, that started to describe the mystery illness and name it after those it was affecting: American Legion veterans.

“And at first, I was told that the Legionnaires weren’t wild about it, but then they accepted it,” Sharrar said.

The discovery of Legionella pneumophila

Scientists and health officials from the city, state and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention began taking a closer look at bacterial causes for the infections. It wasn’t until January of 1977 that they got their answer.

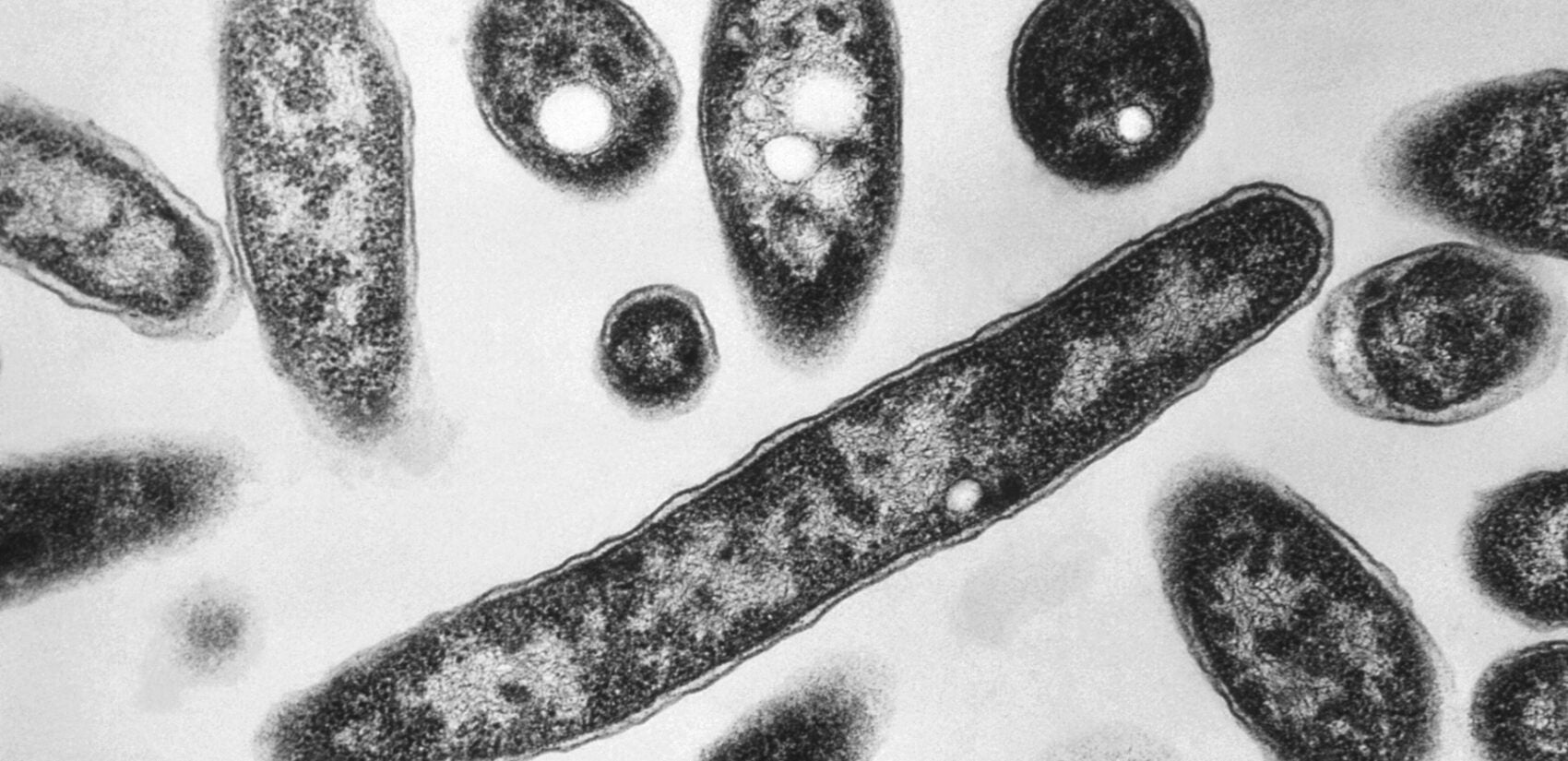

After testing blood samples from patients who had died, experts found the culprit: a common warm-water bacteria that can cause serious illness in people when it’s inhaled in a mist or vapor.

“Once the organism was isolated, by then, the name had been firmly attached,” Sharrar said. “It was only logical to call it Legionella pneumophila.”

Legionella pneumophila: the bacteria that causes Legionnaires’ disease. It’s a common organism that readily grows in water when temperatures go over 80 degrees Fahrenheit and can often be found in shower heads, plumbing and other daily conductors of water.

It doesn’t become dangerous until that water is aerosolized, Sharrar said, which is when the bacteria travels in tiny particles into someone’s lungs.

Public health experts in 1976 suspected that the bacteria had been growing in the Bellevue-Stratford’s air conditioning cooling towers on the roof at the time of the convention, but the towers had been cleaned before they had a chance to confirm.

Nevertheless, scientists now had a name, a list of symptoms and a way to test people. Doctors also discovered that some antibiotics were successful in treating the disease.

“The American Legion were very cooperative during this outbreak investigation,” he said. “I think in some ways it’s probably somewhat comforting to them that the organism has been identified and named and it can now properly be treated.”

Legionnaires’ disease prevention and risk factors

Today, public health and environmental agencies routinely monitor and test water sources like cooling towers and plumbing for Legionella pneumophila so they can eliminate the bacteria before it can infect people.

But when it does cause an outbreak in people, it can still be tricky to identify the source, said Najera, who for many years worked at the Maryland Department of Health and investigated clusters of the disease.

Part of the reason cases of Legionnaires’ disease have risen, Najera said, is because testing has become more advanced and they’re catching cases that would have gone unreported in the past.

There are also more people living with chronic conditions like asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and emphysema that put them at higher risk for severe infection.

The Mütter Museum of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia will open a new exhibit next spring dedicated to the 50th anniversary of the 1976 Legionnaires’ disease outbreak, those who lived it and the public health scientists who didn’t stop searching for answers.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.