Keystone Opportunity Zones not designed to be measured

From where City Controller Alan Butkovitz is sitting, the Keystone Opportunity Zone program in Philadelphia is a major disappointment.

Butkovitz released a report earlier this month saying that the program, which waives nearly all business and property taxes for 12 years, has presented an exceptional burden to taxpayers for a meager return. The KOZ program has cost the city and school district more than $380 million in abated business and property taxes since it began in 1998, according to the Controller’s report. In return, it’s netted $132 million in wage taxes from the 617 businesses that have benefited from the program. What’s worse, more than 70 percent of the wage-tax revenue came from businesses that were already paying taxes in the city before participating in the program.

It’s created just 3,700 new jobs. For each new job, the Controller said, the city has waived more than $100,000 in taxes. At an average salary of $50,000 per job, it would take more than 50 years of wage taxes for those new jobs to pay for themselves.

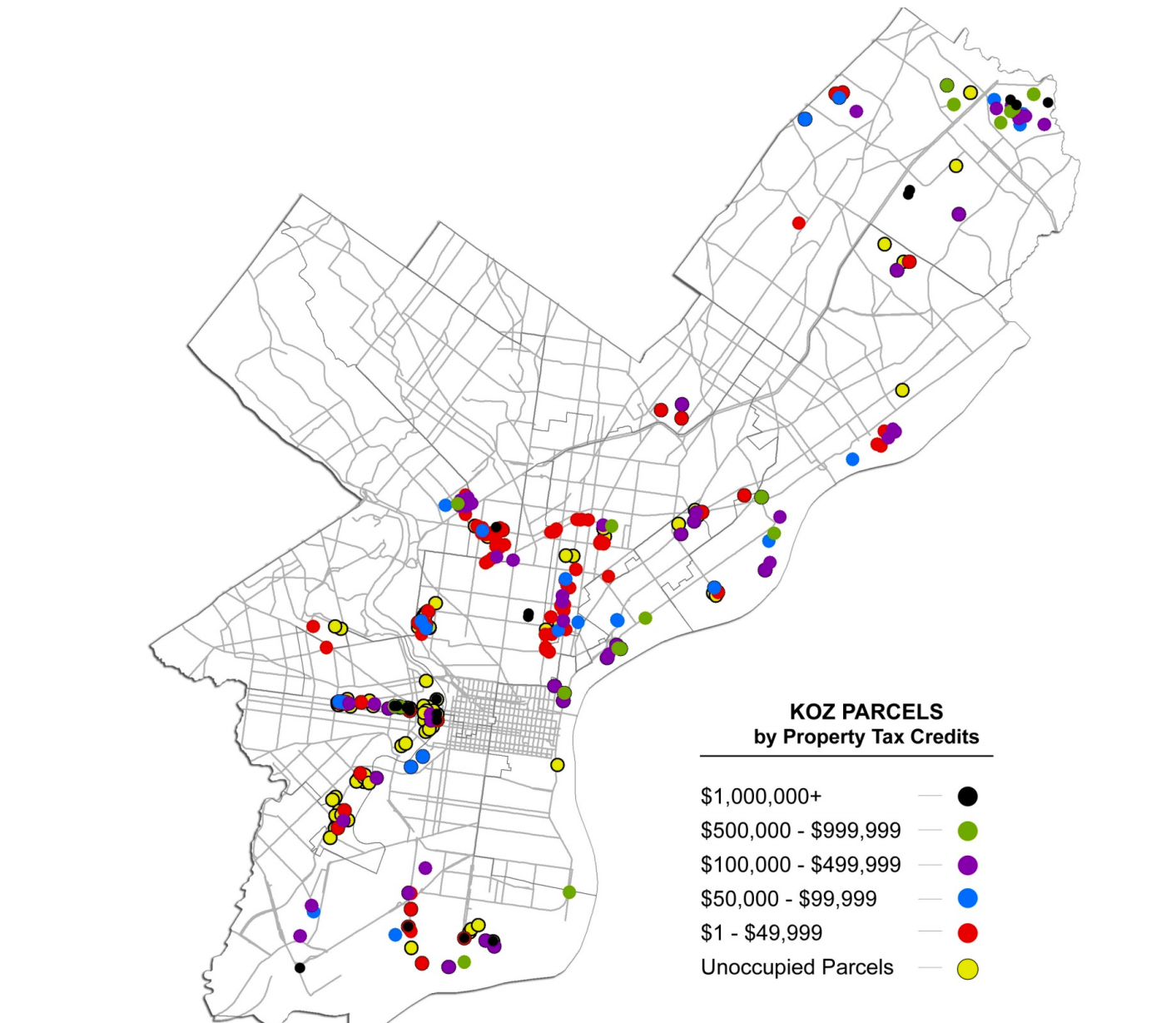

And after all that, more than half the land within Keystone Opportunity Zones is still vacant.

“These findings are consistent with the literature in urban economics, which holds that diffuse tax incentive programs such as the KOZ are an ineffective tool for enhancing economic growth,” the report concludes.

But the City’s Commerce Department isn’t disappointed.

For one thing, said Duane Bumb, the Department’s senior deputy director, the KOZ program isn’t meant to provide a short-term return through wage taxes, the only tax that’s not abated for businesses in the zones. The Controller’s calculation of the number of new jobs created doesn’t take into account how many jobs might have left the city had the program never been created. And the fact that half the KOZ properties are still vacant—some of them are publicly owned and don’t generate taxes anyway—is just proof that there hasn’t been enough subsidy to develop them.

What’s a taxpayer to make of all that?

ABSTRACT GOALS

The Keystone Opportunity Zone program was created by the state legislature in 1998 under Governor Tom Ridge in order “to foster economic opportunities in this Commonwealth, to facilitate economic development, stimulate industrial, commercial and residential improvements and prevent physical and infrastructure deterioration of geographic areas within this Commonwealth.”

Those are worthwhile goals, by most standards, but how can they be measured? The Controller said that his report is the first effort to examine the costs and benefits of the KOZ program in its 15-year tenure. That’s true for a local official, but others have tried to measure the program’s impact in the past.

In 2009, the state legislature’s Budget and Finance Committee released a report concluding that there were “serious deficiencies” in the KOZ program that made its success difficult to measure. Two years later, The Philadelphia Inquirer concluded that, on the one hand, the program failed to spur development and tax growth, and on the other hand, the world may never know exactly what the program did accomplish.

Both accounts noted that there is no system in place to track the tax cost of the program, the amount of investment it generates, or the number of new jobs it creates.

SPARSE RECORDS

“The records necessary to provide adequate oversight of the KOZ Program largely do not exist,” said the Controller, in his report.

The report recommends that the Revenue Department, which is responsible for collecting taxes, and the Commerce Department, which is responsible for attracting new business to Philadelphia, work together to monitor the taxes abated and collected in KOZs, as well as the types of development and jobs they create.

But the Revenue Department is bound by confidentiality policies set by the IRS, which bar it from publicly releasing the tax bills of city businesses. And at the moment, all the data related to job creation in KOZs is self-reported by the businesses getting the tax breaks.

“[There] is no straightforward way to track the progress of the program in terms of job creation or investment continuously over time,” the report says. “Instead only snapshots exist, these occur well after the fact, and they are self‐reported.”

Good Jobs First, a national organization that studies development subsidy programs, gives the KOZ program a score of 0/100 for disclosure, and a 23/100 in terms of monitoring and enforcement.

From Commerce’s point of view, it doesn’t really matter. KOZ beneficiaries aren’t required to meet any job-creation or investment targets in order to get their yearly applications approved.

“Just on the jobs number,” said Duane Bumb, “this idea that there’s self-reporting, and what if they’re lying to us? I guess I would say, they’re not motivated to lie to us, because whatever that number is, there is no wrong answer … The program doesn’t have specific requirements to say, ‘You must have or grow this many jobs.’”

NUMBERS GAME

Bumb said that according to the Commerce Department’s figures, which are taken from the self-reported KOZ applications, twice as many new jobs have been created as the Controller reported. He said the Controller’s office approached its analysis as an auditor would, only counting those numbers that could be verified independently. He understands the approach, but questions whether the Controller’s method—reverse-calculating the jobs created based on the wage taxes paid—is reliable.

“The fact that they can’t somehow validate those jobs doesn’t mean they don’t exist,” Bumb said. “I don’t actually accept that. … We’re using a different series of numbers. I do not doubt the validity of the numbers we have, but since they can’t validate those, they’ve sort of taken the position that if you can’t prove that the company was going to leave the city, the jobs that the company started with when it went to the KOZ don’t count. There’s nothing I can do about that.”

Vince Dougherty, the coordinator of the city’s KOZ program, pointed to the case of Case Paper, a Kensington paper distributor also cited in a 2011 Inquirer story about the program. The company was planning to move dozens of employees to a property in Bucks County, but after the city designated its property as a KOZ, the company decided not only to stay but to consolidate its regional employees in Philadelphia.

WHAT’S A ‘BUT FOR’?

Most arguments about the need for public subsidies in private development tend to end with an inherently unprovable claim: a new building that claimed some subsidy wouldn’t have been built without it. That’s the line of reasoning followed by developers and elected officials who defend the city’s 10-year property-tax abatement, for example. But for the abatement, much of the new construction in Philadelphia never would have happened.

Lee Huang, an economist with Econsult Corporation, praised the Controller’s office for looking into the KOZ program. He said he’s looked into it himself, and considers himself a proponent. One thing he recommends is to consider not just whether there’s a dollar-for-dollar return on investment in the program, but whether it’s created an “overall investment effect.”

“I think that while it’s hard to prove, I think it’s pretty clear that there’s a lot of investment that would not have happened but for the KOZ,” Huang said.

Some developments do belie that claim though. When Comcast was building its first skyscraper in Center City, then-Governor Ed Rendell supported designating the site as a Keystone Opportunity Zone. But the deal was shot down, and the tower was built anyway.

Vince Dougherty pointed to development at the Navy Yard as an example of the KOZ program’s success. Even with all that success, he said, half the yard is under KOZ abatement and still undeveloped.

LINGERING VACANCY

In some cases, developers have enjoyed tax relief without actually building anything.

In Brewerytown, developer John Westrum owns an empty block across from a townhome community he built a few years back known as Brewerytown Square. The owners of those townhomes now enjoy the standard ten-year tax abatement for new construction, but Westrum has also paid no property taxes on the adjacent vacant lot for the past ten years, since it was part of a Keystone Opportunity Zone that expired at the end of last year.

“The intention of the KOZ was always to create jobs and to create some type of a non-residential use,” Westrum told PlanPhilly. “So our understanding and agreement was that we were able to keep [the properties] as KOZ zones while they were undeveloped, but when we built on them we would give up the KOZ status.”

On Columbus Boulevard, the property owned by Waterfront Renaissance Associates that was once slated to become the Philadelphia World Trade Center, has also enjoyed KOZ benefits, even though it’s been empty for decades. Development plans at the site were caught up in a morass of legislation and litigation that led to the demise of both the Old City Civic Association and the River’s Edge Civic Association. But year after year, the KOZ was renewed, because the program has no participation requirements.

The program has evolved since its inception, and the Commerce Department said it now has more ways to target the benefits to properties that are actually seeing development. Further up on the Delaware River, a huge property owned by Jim Anderson that was the site of the proposed Wynn Casino is also in a Keystone Opportunity Zone. But the owner of that property can’t claim any of the tax benefits until the property is occupied. The KOZ expires in 2015.

A TOOL IN THE TOOLBOX

Other programs have been more controversial. Late last year, City Council approved a $33 million Tax Increment Financing [TIF] district for a W Hotel at 15th and Chestnut streets. Under that program, developers may keep up to a certain dollar amount in taxes for the first 20 years of the development. But that program has clawbacks built in. If the property doesn’t generate sufficient revenue in the first 20 years to pay off the TIF, the developer is on hook for the balance.

Programs like the Keystone Opportunity Zones are among the most common economic development programs in the country. But Good Jobs First considers it an “old, unfocused, and outmoded” approach to economic development.

The Commerce Department maintains that it’s worthwhile.

“KOZs have real value because we know the outcome going in,” said Duane Bumb. “So if we’re talking to a company and there’s some huge gap in financing that we have to figure out how we close that for them to do the investment that we all want them to do and create the jobs we all want them to create, the great thing about the KOZ program is that, if the site you’re talking about is KOZ, and if that’s what makes it work, then we’re done. [Tax Increment Financing] is a great program, [but] when we go to City Council and to the School District to sell that, there’s no certain outcome. So some of this is the certainty of it.”

But that’s a certainty that benefits the KOZ participants. As the Controller’s report demonstrates, there’s no certainty for those who want to understand the program’s performance.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.