‘Juvenile In Justice’ starkly portrays abuses of U.S. detention system

The gallery space inside the Crane Arts Building in Kensington is called “The Icebox.” At some point during the building’s 108-year history, it was used to process frozen seafood.

The enormous concrete space has no windows. It is — literally — a cold, hard place.

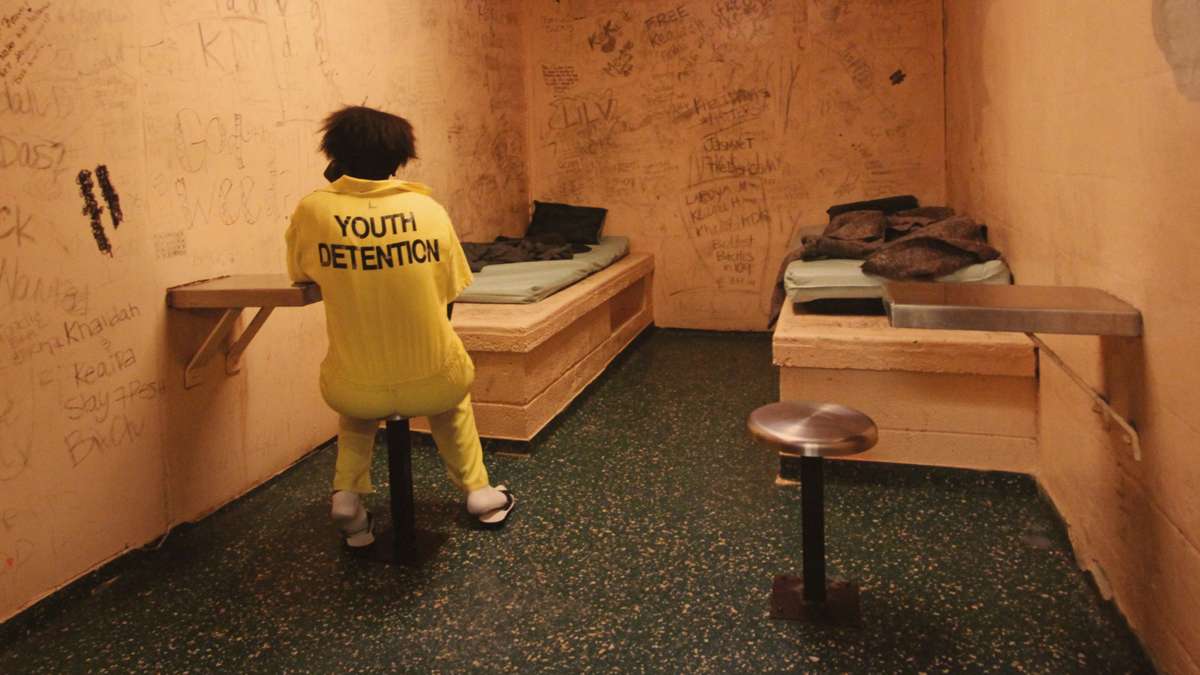

It’s fitting that it would be hung with more than 70 large-scale photographs of teenagers held in juvenile detention facilities around the country. The unframed pictures are hung by clips, as from a clothesline, and the faces of their subjects are obscured, sometimes in creative ways.

Photographer Richard Ross has spent seven years crisscrossing the country, visiting hundreds of detention facilities and talking to teenagers, some of whom were held in dehumanizing conditions for minor crimes of jaywalking, truancy, and possessing small amounts of marijuana.

“Most of the kids are in here for pissing off an adult,” said Ross, 66, a professor of art at the University of California, Santa Barbara. “They’re in here for nonviolent crimes, non-‘person-on-person’ crimes.”

In the middle of the space is a box measuring about 7 feet by 10 feet by 9 feet, the dimensions of a typical cell.

“Welcome to my world,” said Ross, 66, going inside and shutting the metal door behind him.

“This for me is bliss,” he said, sliding his back down a blank, white wall to sit on the concrete floor (he has chronic back problems). “When I’m able to listen to a kid’s story, and they tell me their lives, it’s a total privilege that you rarely get.”

This show, “Juvenile In Justice,” opening this weekend, is the central piece of a three-part exhibition throughout the Crane Arts Building, curated by Julian Robson and Rachel Zimmerman of InLiquid.

Breaking barriers with fine china

The second part, in the adjacent room, is an exhibit of ceramic work by Roberto Lugo, whose work is informed by graffiti and growing up in the ghettos of Kensington.

“I usually woke up to prostitutes on my steps as I left to go to school every morning,” said Lugo. “If you forget that you live in the ghetto, as soon as you open that door in the morning, you’re confronted with it.”

The problems were only compounded at school. As he would arrive at Kensington High School, Lugo remembers having to take off his shoes, pass through a metal detector, and allow security guards to look under his tongue for razor blades.

He used to run with his brother, tagging walls and signs around the city. His brother, the graffiti artist known as Maz, is currently incarcerated, as are several of Lugo’s cousins.

Now working toward an advanced art degree at Penn State, he makes vases in the style of Herend porcelain — fine china made for 19th century European royalty. His vases and vessels are tagged with street-art script and his own image.

“That’s where we start to desegregate as a society,” said Lugo. “Where we are welcoming and we don’t think it’s an odd thing to see a Puerto Rican man on a really fancy vase.”

Abstract reaction to frustrating reality

The final exhibit is a series of 94 abstract paintings by Mat Tomeszko, created mostly during a five-week artistic residency in Covenant House, a Kensington youth shelter. The number of paintings references the “94 Effect,” a theory that a homicide directly affects 94 people.

Shortly after Tomezsko graduated from high school in 2005, a good friend of his was accidentally killed by gunfire in the Point Breeze neighborhood. The paintings are, in part, his reaction to that death. The abstract pieces are a grid of mostly earth-colored streaks, or thickly layered washes, or text that cannot be deciphered.

“It’s about frustration, and reacting to that frustration,” said Tomezsko. “There’s a lot of repetition. I’ll do the same streak painting, or word painting, over and over again. It’s waking up every day and approaching the same thoughts over and over again.”

The three parts of the show form a exhibition of social advocacy, calling for attention to youth wrongfully incarcerated and the need for better means of rehabilitation.

“It was sort of timely in the sense that what’s happening in public schools with the with lack of art education,” said curator Zimmerman. “This was a perfect statement to say, ‘Hey, art is important. It saves lives, and it’s critical to save our youth.'”

The exhibit continues through Dec. 12 at the Crane Building, 1400 N. American St., Philadelphia; Monday through Saturday from noon to 6 p.m.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.