Fashion students at Jefferson make clothes for Philadelphians with prosthetics, skin sensibilities and other conditions

"Fashion can't just be about designing pretty clothes," said the program director.

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

Finding clothes that fit was just one of many things that became more difficult for Teto Saunders after his leg was amputated above the knee because of a gunshot wound more than 20 years ago.

His pants and shoes have to fit over his prosthetic leg, which means they’re often too big for him.

“I felt very uncomfortable oftentimes being out in the community, even when it came to dress wear, finding appropriate shoes that wouldn’t cause me to slip or slide or feel uncomfortable and then finding pants that wouldn’t dig into the prosthetic,” he said.

He said that even when he finds pants that fit, it can be hard to get into them, unless they can open from the side so he can have easy access to his prosthetic. He explained that sometimes it can take 15 to 20 minutes to get dressed and changed.

Then he had the opportunity to have clothes created specifically for him. For a few months, he worked with fashion design students at Thomas Jefferson University, who learned about his life, what he looks for in clothes and what he likes to wear. Then they designed clothes specifically for him, including dress pants that fasten with magnets along the side, and pants with a zipper that goes all the way up the side, meaning he can easily access his prosthetic without having to take the pants off.

“This experience has caused me to come out of my comfort zone: of feeling that there was nothing out there for me, and then finding things that did fit me,” Saunders said. “Now I’m expanding even more to being open to different designs, different patterns.”

Designing for people the industry has overlooked

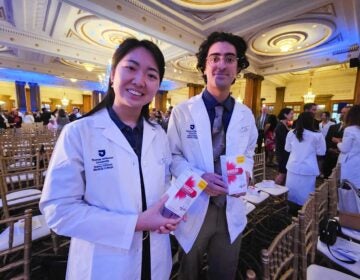

Jefferson has offered this class for a few years to teach students about designing for people whom the fashion industry has traditionally overlooked, like people with disabilities, skin sensitivity and conditions like autism. But this is the first time the class had students work with actual clients.

Fashion design major Gabriel Malis said that before the class, he had mostly designed for himself and his own family, who are all tall and skinny.

“It gave me the chance, obviously, to work socially a bit more outside of myself and my own circle,” he said.

He said it was also a special experience because he’s on the autism spectrum, and worked with a client who is also on the autism spectrum, but thinks about clothing differently than he and his friends.

“They just kind of wear what they want and … they don’t really think about it that much. They just go as long as it’s not, say, for example, wool. It’s too itchy,” Malis said.

But when it came to the client he worked with, architect Rachel Updegrove, he had to consider that she wanted clothing that was not itchy, breathable, soft and included some smaller detail that she can pick at and play with when she fidgets.

Malis made her a light, breathable wool blazer with gold buttons.

Updegrove said she had a good experience with the students in the class. She experiences issues with temperature regulation, and said the students really took her needs into account.

“Their sensitivity to me and my temperature regulation was really awesome because I’m extremely self-conscious about how warm I can get and overheat and sweat,” she said. “A lot of the students often were relating to some of my sensory experiences. There’s such a wide range within the autistic community of needs, I hopefully just let them see autism in a different way than what was kind of stereotyped in the past.”

A growing, multibillion-dollar market

Carly Kusy, the program director at Jefferson, said this class is part of their philosophy that “fashion can’t just be about designing pretty clothes anymore,” that they hope to improve the industry.

She explained that this is a required course for students in their senior year, and that this will prepare them for the job market.

“The adaptive wear market is huge and it’s continuing to grow year after year exponentially,” Kusy said.

Well-known brands like Anthropologie, Target and Tommy Hilfiger already make clothes that fit people with disabilities and chronic illnesses. That market is worth billions of dollars, and continues to grow.

The fashion industry has not designed for these underserved populations in the past largely because of ignorance, said Domenica Vinci, assistant professor in fashion design, an instructor for the course and a longtime fashion designer.

“There was an ignorance of thinking, ‘Oh, someone in a wheelchair doesn’t care to be fashionable. They’re okay just wearing sweatpants.’ But when you do talk to them, they do like fashion,” she said. “Just because you have crutches doesn’t mean that when you go to a concert with your friend, you don’t want to wear the same leather jacket as your friend is wearing.”

It’s been “really wonderful” to see that inclusive design is now part of curriculum, because it wasn’t common in the past, said Yasmin Keats, executive director for the nonprofit Open Style Lab, an organization founded out of MIT that runs multidisciplinary education programs to “design with people with disabilities and not for them.” In 2017, the group worked with the Parsons School of Design in New York on a program similar to Jefferson’s.

Keats said that now, their goal is to have disabled leaders in design and engineering, because collaborative design is more than working together in a classroom setting.

“You learn more from those in-between moments when you’re going to get coffee together … or when you’re having a break or you’re catching the train together — you’ll learn more about someone’s life around disability in those environments than you will in a classroom. And so we do a lot of work in creating those environments and encouraging that real equity and collaboration because disability does not affect you in a vacuum. It affects you at every point of your life or every point of your day.”

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.