It’s time to finish King’s work on poverty

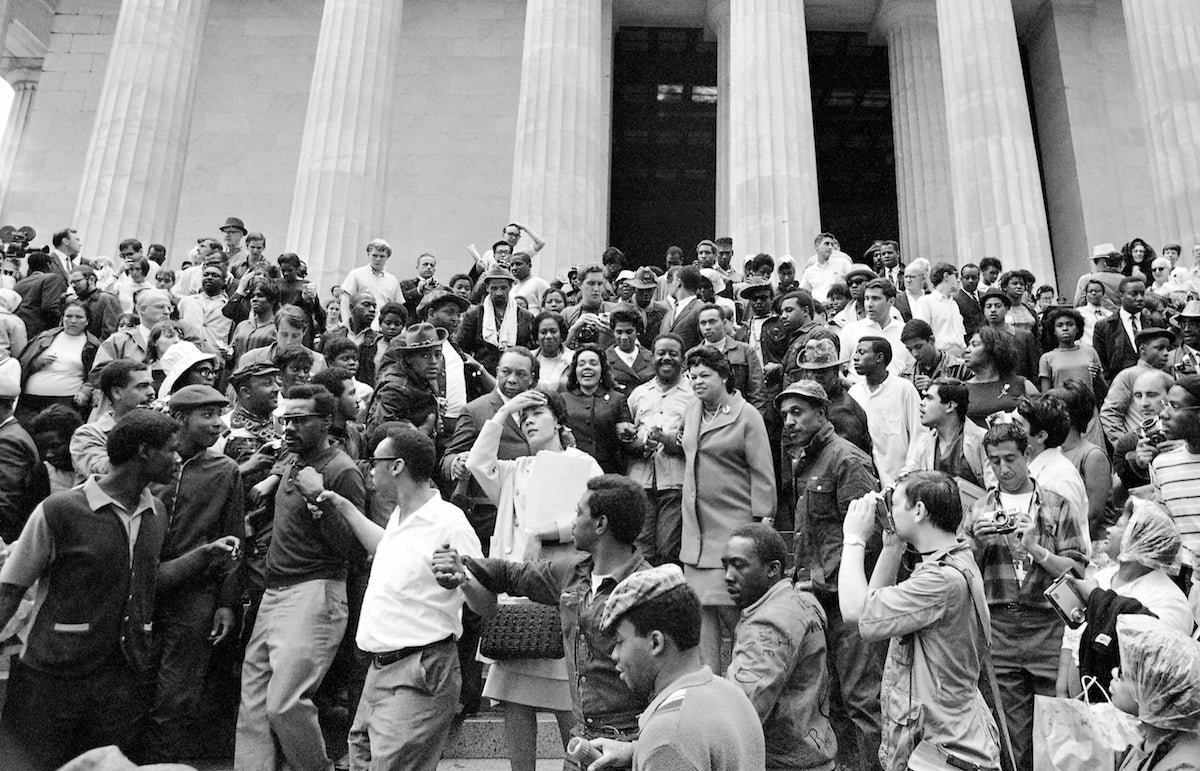

Coretta Scott King, center, is surrounded by members of the Poor People's Campaign, on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, May 30, 1968. (AP Photo/Bob Schutz)

I have often thought that Martin Luther King Jr.’s legacy is woefully incomplete. We celebrate him as an almost mythical figure whose sole purpose was to eradicate racial injustice.

King, if he were alive, would beg to differ with that assessment, because he fought for far more than racial equality. He fought to dismantle the very system upon which racial segregation was built and maintained. He fought to eradicate poverty.

Toward the end of his life, King realized that the moral high ground could be a lonely place, if it was built upon a hill of poverty. He realized that in a capitalistic society, political power meant little unless it was coupled with economic gains. Having won passage of the Voting Rights Act and the Civil Rights Act, King pivoted to a larger challenge.

He began to assemble the Poor People’s Campaign.

That campaign was not predicated on social programs. It was centered on jobs. He wanted to bring together 2,000 people to convene in the capital to demand jobs, fair wages, better education and unemployment benefits. King had come to understand that the poor weren’t always people who were without jobs. The poor were also people who worked.

“The problem of unemployment is not the only problem,” King said in a speech in Grosse Point, Michigan, a month before his death. “There is a problem of underemployment, and there are thousands and thousands, I would say millions of people in the Negro community who are poverty-stricken – not because they are not working, but because they receive wages so low that they cannot begin to function in the main stream of the economic life of our nation. Most of the poverty-stricken people of America are persons who are working every day, and they end up getting part-time wages for full-time work.”

But King also realized that poverty was not just a black problem, so he did something far more radical than he’d ever done in fighting for the Civil Rights of African Americans. He reached out for those whose economic conditions were similar to those of poor blacks.

He extended a hand to poor whites, the very people who’d served as the foot soldiers on the battlefield of Jim Crow. He reached out to the poor migrant farm workers who harvested America’s food. He sought alliances with the Native Americans who lived in crushing poverty on reservations.

He began to forge partnerships that crossed social and ethnic lines. He focused on economic freedom. That’s what he was doing when he was assassinated. He was preparing to support Memphis sanitation workers who were striking for higher wages and union representation.

Therein lies the irony. The same economic battle that King waged nearly 50 years ago is still raging. The income gap between rich and poor is still widening. But now, a new cadre of activists has taken the mantle, and like King did, they are agitating for a fair living wage.

The fight to raise the minimum wage to $15-an-hour has ebbed and flowed, producing victories in cities like Seattle and San Francisco, but languishing in other places across the country.

I wonder if those activists know that King tried to wage that same battle. I wonder if they know he was fighting for fair wages at the end of his life.

Perhaps they should be as intentional as King was in gathering a diverse group of allies. Perhaps they should be more strategic in letting the rest of us know how poverty affects us all.

Because as King said in his seminal work, Letter From a Birmingham Jail, “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.” He was talking about race in that letter. But he could have very well been talking about poverty.

It’s time for us to complete Dr. King’s effort to bring justice to the working poor.

It’s the best way to pay tribute to his legacy.

Listen to Solomon Jones weekdays from 7 to 10 am on 900 am WURD

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.