In Pa. jails, women are paying more than double for the same tampons they’d get on the outside

A PA Post analysis found that the private companies in charge of providing goods to inmates are price-gouging items. But their contracts say that’s not allowed.

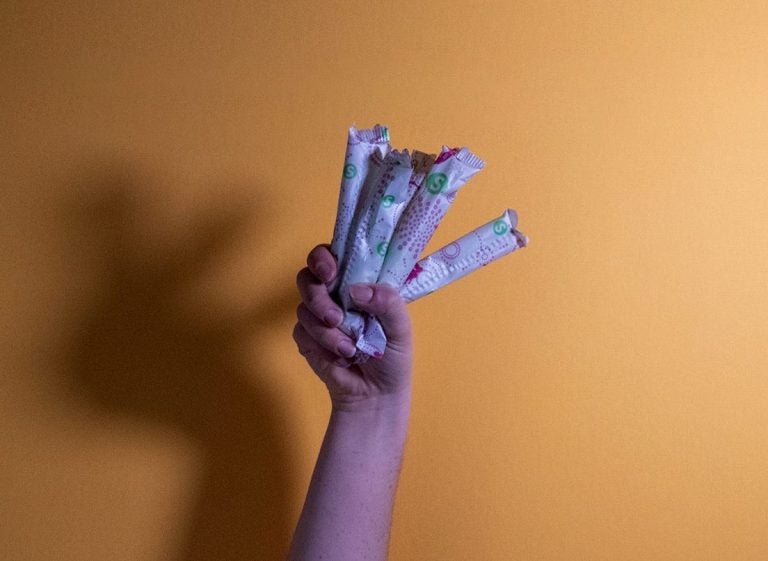

(Joseph Darius Jaafari/PA Post)

This article originally appeared on PA Post.

—

When Rachel Santiago began serving a sentence at the Riverside Correctional Facility in Philadelphia, she had to surrender all of her clothes. In exchange, she was issued a pair of prison scrubs and some basic toiletries: a toothbrush and toothpaste, a small bar of soap, a pair of socks and five small packets of shampoo.

But since it was her first time in jail — she was charged with child endangerment after her son and nephew found a gun in their home and discharged it, injuring her son — Santiago didn’t know that she had to make the prison-issued supplies last.

Basic necessities – tampons, shampoo, soap – are not guaranteed to inmates. Santiago needed to purchase those items through the jail’s commissary, using funds contributed to her account by family members.

“If you’re a normal person and shower every day like I do, those five shampoos go away in, like, two showers,” she said. “But you have no choice. You have to buy these things in order to live like a basic human.”

In Pennsylvania and across the country, commissaries are typically operated by private companies that pay a portion of their profits to the host correctional facilities, amounting to millions of dollars a year in revenue that’s fed back into their budgets.

In some Pennsylvania counties, as much as 46 cents on the dollar is returned to the jails as a commission. But given that inmates don’t typically hold jobs — and if they do, they are paid a fraction of the minimum wage — prisoners’ rights advocates and bipartisan criminal justice reform groups say that jailers are taking advantage of a notoriously poor population.

Little research exists on the costs of commissary items and how prices are set. In 2018, the Prison Policy Initiative — a prison research organization — compared similar or exact products sold both in retailers and prison commissaries and found there were nominal differences between costs.

But a PA Post analysis of prices charged at 10 Pennsylvania jails found that commissary items are consistently priced higher than what they would cost on the outside, despite county contracts that require jails to set prices at levels similar to those charged in regular stores.

For example, dried ramen soup packets bought at retail stores like Walmart or RiteAid for as little as 10 cents are marked up 800 percent at some jail commissaries. And basic necessities, such as soap, are priced at well over twice what’s charged at outside retailers.

The most striking cost disparity is found among feminine hygiene products. Individual tampons are priced more than double what women are charged on the outside. One inmate described a constant worry about not having enough tampons for her menstrual cycle. A handful of other women interviewed said they resorted to making their own pantiliners by cutting up old underwear or rags and wrapping them with toilet paper.

County officials are sympathetic to inmates’ complaints, but argue that the items sold at their jails aren’t necessities. Yet inmates, family members and their advocates argue that it’s impossible to survive incarceration without buying things from the commissary.

Location, location, location

In our analysis, we found that where inmates are incarcerated determines how much they spend on commissary items.

For example, bars of Dial soap cost less for inmates housed in Wyoming County than they do in Clinton County, where the price is 20 cents more. Tampons in Bucks county cost inmates 24 cents each, compared to 35 cents in Clinton. Getting 4 ounces of a cocoa butter lotion in Franklin County will set back a prisoner 65 cents; the same product in Butler County costs nearly $3.

Wardens at multiple jails said prices are set by the private commissary companies. In Pennsylvania, two companies — Keefe Group and Oasis Management Systems — hold most of the contracts. (Neither companies returned phone calls and messages requesting more information on how they price their commissary items.)

In county contracts reviewed by PA Post, the jails stipulate that “prices for commissary items may not be higher than comparable items offered for retail sale in a sampling of grocery stores, and convenience stores in the area.”

But there is no direction in the contracts on how the commissary companies should analyze local prices, and it’s unclear how the companies identify costs to carry out pricing comparisons.

In those counties where jailers are aware of price discrepancies, they say the higher prices take into account the private company’s costs of managing the commissary.

“The pricing factors in costs for goods purchased, packaging, and delivery,” said Bill Bechtold, the warden for Franklin County’s jail, in an email. “Mark ups also cover a range of commissary operational costs (e.g. the purchase and installation of commissary kiosks in each housing unit, the purchase and installation of a booking and a public kiosk for money deposits, banking services software, order fulfillment and delivery, customer service regarding complaints and refunds, etc.).”

Deciding between food or hygiene

PA Post’s analysis of commissary costs did find cases where items cost less than what is charged on the outside. For example, cocoa butter body lotion is priced as low as 65 cents in Franklin County. Buying a similar lotion in the store or online would be closer to $1. And pantiliners — which are often sold in bulk — have comparable prices when broken down to individual items, at about 11 cents a pad.

Similarly, the Prison Policy Initiative’s report found that the items they compared were often cheaper at prison commissaries, but the report cautioned that those items shouldn’t be seen as deep discounts.

“While $1.87 may sound like a fair price to pay for a month’s worth of dental floss, the transaction feels very different from the perspective of someone in a Massachusetts prison who earns 14 cents per hour and has to work over 13 hours to pay off that floss,” the researchers wrote.

Many county jails follow state prison guidelines to determine the pay rate for inmates who are lucky enough to secure a job working inside the jail. The Pennsylvania Department of Corrections set hourly rates in a 2008 directive, establishing inmate pay to fall anywhere from 19 cents to 75 cents an hour for more technical skills, such as asbestos abatement.

And with such low wages, trying to afford hygiene products becomes a cumbersome task.

“You have to really decide if you want to get hygiene products or eat,” said Vincent Rush, a recently released inmate from Dauphin County Prison who was held for close to a year on a parole violation. “Even if you make $20 every two weeks, that doesn’t get you far.”

Prison officials insist that the items bought from commissaries aren’t the necessity that family members or advocates on the outside make them out to be.

“I can certainly understand both sides,” said Tammy Moyer, director of administration at Lancaster County Prison, adding that there is a difference between the definition and perceived reality of what inmates’ basic needs are.

“We try to strike the right balance between protecting taxpayer dollars and not overcharging inmates,” Moyer said. “Just to be clear, inmates are provided all necessary food, clothing and hygiene items to meet their basic needs. Any items purchased from commissary go above and beyond basic needs and are paid for by the inmate.”

Prisoner advocacy groups say that argument misses the point, and shows jail officials don’t understand why inmates believe that commissary items are almost a requirement for survival.

“We are punishing them by taking away their liberty, and then we’re punishing them and their families by not even giving them enough soap,” said Lisa Foster, co-founder of the Fines and Fees Justice Center in New York. “It’s as necessary as sleeping or eating.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.