I-95: where do we go now?

By Matt Blanchard For PlanPhilly

Following the river’s course at an average of three city blocks inland, the construction of Interstate 95 in the 1960s and 1970s cut a path of destruction through what had been the heart of maritime Philadelphia: a dense collection of old warehouses, wharves, factories and homes that, had they survived, might be some of the city’s most desirable real estate today.

The current effort by the city, PennPraxis and the Philadelphia community to create a comprehensive plan for the Central Delaware Riverfront seeks to re-stitch the urban fabric and reconnect neighborhoods to the river.

But up and down the 7-mile planning area, I-95 acts as a physical and psychological barrier. In Center City, a sunken 10-lane segment forms a 380-foot canyon separating Penn’s Landing from Old City. In Northern Liberties, the road and its ramps present a concrete wall, blocking both access and views. And in South Philadelphia, Kensington and Port Richmond, I-95 runs on an elevated viaduct supported by concrete pilings. Traffic flows beneath, but the highway’s dank underbelly discourages strollers and decimates the value of nearby homes.

So it’s worthwhile to ask: Why was I-95 built along the waterfront in the first place? Why would the city turn its back on the river and plow down so much prime real estate for a road? And now that it’s here to stay, are there innovative ways to lessen I-95’s impacts on the neighborhoods?

“Tackling I-95 is a critical challenge, and we shouldn’t be afraid of addressing it,” said PennPraxis director Harris Steinberg. “It’s a question of where we put our efforts. I don’t think we’re going to change the course of I-95 in our lifetime. That said, there are places we can have an impact.”

The following is a brief sketch of the highway’s history, the reasoning behind it, and a collection of proposals for how the highway might be incorporated into – or be dynamited out of – the future of Philadelphia’s waterfront.

Origins

Philadelphia’s I-95 is, of course, just a small segment of the major north-south highway linking East Coast cities from Miami to Maine. In all, it is some 1,927 miles long, and is the most heavily traveled portion of the nation’s vast interstate highway system, authorized by Congress in 1956.

Dwight Eisenhower had encountered Germany’s autobahn system during the war in Europe and, as president, championed two major justifications for the American interstates: Speeding everyday commerce and travel, and allowing rapid troop movements in the event of invasion. With Cold War tensions running high, the interstates were also imagined as valuable evacuation routes from major cities in case of nuclear attack.

Philadelphia’s segment, called the Delaware Expressway, has origins before Ike. According to highway historian Steve Anderson, creator of the deeply-researched website www.phillyroads.com, the Philadelphia City Planning Commission proposed a similar road in 1937, the so-called “Delaware Skyway,” an elevated industrial highway above Delaware Avenue.

The Skyway never flew, but planners revisited the concept as the automobile age moved into high gear after World War II, approving something like the current I-95 concept in 1947. A report of the Philadelphia Planning Commission from that time, provided by Anderson, explains the reasoning behind the road:

The great industrial area that runs from the Trenton area south to the Wilmington area is clustered largely along the banks of the Delaware River. The critical need of the area is a north-south express highway, running close to the Delaware River, which will link together this great industrial complex.

Merely listing the various sites that are tied together by the Delaware Expressway makes self-evident the tremendous advantages of the proposed highway. It connects with the U.S. Steel plant at Morrisville; with the Levittown, Fairless Hills and other rapidly expanding residential areas of lower Bucks County; and with the Pennsylvania Turnpike, which in turn will link through a new bridge with the New Jersey Turnpike, thus providing rapid access from Philadelphia into northern New Jersey and New York.

The Delaware Expressway will provide quick access into the downtown Philadelphia area from the populous Northeast; connect all the industrial plants along the Delaware River; connect through interchanges with the Tacony-Palmyra, Philadelphia-Camden (Benjamin Franklin) and Philadelphia-Gloucester (Walt Whitman) bridges; connect the Port of Philadelphia with the whole area; provide rapid access to Philadelphia International Airport from the entire region; and provide a rapid highway from New York into the Wilmington and Baltimore-Washington areas.

Implicit in this reasoning is a view of Philadelphia’s waterfront as an industrial powerhouse for which the rapid movement of people and cargo was paramount. And for three centuries, that view was justified; the Delaware was at the heart of a region dubbed “The Workshop of the World.”

While the early 19th century waterfront did retain a few beaches and green spaces, the mid-20th century river was lined with heavy industry: railroad depots, steel rolling mills, oil storage tanks, lumberyards, cargo piers and factories. As roads supplanted rails, these industries needed highway access to remain competitive. Downtown offices, too, needed highway access, and it was no great shakes if obsolete multi-story factory buildings were bulldozed to provide it. Our contemporary vision of a grassy riverfront with biking trails and cafes had no place on this utilitarian waterfront, just as lace doilies and tea service have no place on a carpenter’s workbench. As Penn urbanism professor Witold Rybczynski writes, “Only recently has the waterfront – once smelly, noisy and dirty – been seen as an amenity.”

Construction of I-95 began in 1959 in Northeast Philadelphia and would not end until 1985.

Opposition in Center City

If there was citizen opposition to the roadway in the river wards of Port Richmond and Kensington, it appears to have had little impact. Citizen opposition in Society Hill was more vocal. An architect named Frank Weise led resistance to the road after viewing a scale model of the project. The model showed an elevated monster looming over the city’s most historic neighborhood. Architecture critic Inga Saffron recounted the story in The Philadelphia Inquirer:

It was 1963, and a scale model of the proposed interstate was displayed in John Wanamakers. But as soon as Weise glimpsed the exhibit, he realized that the superhighway would barrel through one of America’s most historic neighborhoods, cutting off Center City from the Delaware River.

Weise, now 84, went to see Philadelphia’s top planner, Edmund Bacon, and warned him that Interstate 95 would doom the city’s dream of populating its waterfront with housing, parks and shops.

“Bacon told me I was off my nut,” Weise said in an interview. “He told me I wasn’t living in the age of the automobile. “

Bacon was wrong. Weise was right. No other factor has shaped the fate of Penn’s Landing over the last three decades as much as the construction of the Center City portion of I-95, completed in 1979.

Weise was ignored, but not discouraged, Saffron explains.

After Weise was rebuffed by Bacon in 1963, he organized a committee of architects to form alternatives to the I-95 design.

The committee proposed that the Center City portion of the interstate be sunk below the level of Front Street to protect views of the Delaware River. On top of the sunken highway, they wanted to see a six-block cover that could hold new city streets and buildings.

As a result, a federal committee was formed by Vice President Hubert Humphrey to reassess the highway design. The group accepted the criticism (from the architects) and ordered the federal government to depress I-95 below grade from Market to Lombard Streets.

But Humphrey’s group rejected the six-block cover because of the expensive ventilation required for such a long tunnel. Instead, the federal government decided to cover just two small sections at Chestnut Street and between Dock and Spruce Streets. These concrete tops are not strong enough for buildings.

Covering I-95

The government’s failure to cover all of I-95 in Center City remains a hot-button issue. Newcomers to the area are frequently amazed that planners covered only two short sections of the highway, isolating Penn’s Landing. This sentiment found its strongest expression during public forums on the future of Penn’s Landing conducted by PennPraxis and The Philadelphia Inquirer in the winter of 2003. Participating citizens overwhelmingly favored plans that feature completing the cover over I-95 to create either a large, sloping park or a new neighborhood of apartments and shops.

Examine the Penn’s Landing plans by clicking here.

Historian Steve Anderson adds two points of interest to this ongoing discussion. The first is that City Council’s original 1960s vision for I-95 did include much larger cover over the highway, six blocks from Pine Street north to Arch. This 15-acre area was meant to support new buildings and parks. Otherwise, Council feared the highway would become an “ugly, noisy open ditch.”

A second point mentioned by Anderson is that while only two blocks were covered, the retaining walls of the four open blocks were designed to take the weight of concrete covers, since designers assumed such covers would be added in the future. If true, this would suggest I-95 was made to be covered. Read Anderson’s full article at www.phillyroads.com/roads/delaware/.

PennPraxis’ Steinberg says engineering challenges should not limit the public planning process. Buildings, parks, and other features can be built above I-95, just as such things happen in other cities. “We can do it. It’s just a question of if we have the political will and the capital to do it,” he said. “Let’s use this as an opportunity to dream.”

A new solution for Penn’s Landing

Architect Gil Rosenthal of Wallace, Roberts and Todd has proposed a startling way of reconnecting the urban fabric of Old City to Penn’s Landing: Raise the level of Delaware Avenue. To se his idea, click here.

It may sound backwards, but some time ago Rosenthal noticed that the bridges over I-95 at Walnut and Chestnut arch high above the level of Old City – not to cross the sunken I-95 – but in order to get over Delaware Avenue, which is as much of an obstacle as the interstate.

“Most people don’t realize that part of the problem of crossing I-95 is crossing Delaware Avenue,” Rosenthal said. “At the same time, we believe Delaware Avenue could be a gorgeous waterfront boulevard.”

Reconsidering the topography of Penn’s Landing, Rosenthal struck upon a simple fix: By gradually sloping Delaware Avenue up so that it was on a level with Front Street between Walnut and Chestnut Streets, he could continue the Center City street grid straight over I-95 with minimal interruption. Pedestrians would cross I-95 much as they do the Vine Street Expressway and encounter an improved Delaware Avenue.

“Delaware Avenue becomes a city street. It really is another city street at the elevation of the city,” Rosenthal said. “It extends the city seamlessly, without needing the huge investment of decking I-95.”

Capping I-95 with buildings

Rosenthal said his concept would also open development parcels over I-95.

“If you took the Walnut Street bridge and lined it with buildings that are only 30-feet wide, the impact of the highway would disappear completely,” he said.

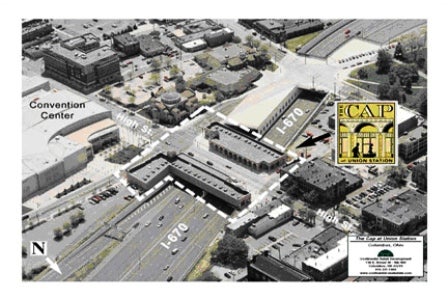

Capping a highway with buildings has had great effect in Columbus, Ohio.

These cars on High Street in Columbus, Ohio are crossing ten lanes of Interstate 670, but you wouldn’t know it. The highway is capped with low-rise stores and eateries built in 2004. The development, called The Cap at Union Station, is shallow, however, leaving much of the highway open to the sky and obviating the need for expensive highway ventilation systems. Image from Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Image:Cap_at_Union_Station.jpg

This aerial image of the same development from the website of Continental Real Estate Companies shows how shallow the buildings are. It’s not so much a highway cap as it is a retail strip hung on the side of the overpass. It has been likened to Florence’s Ponte Vecchio.

To see an entire roster of other buildings constructed over interstate highways across the nation please see this article from Wikipedia.

Blowing up I-95

Back in 2002, one civic leader made an interesting case for demolishing I-95 south of the Ben Franklin Bridge. Speaking to the Inquirer, Center City District director Paul Levy argued that removing a section of the highway from Vine Street to Washington Avenue would open up land for extensive development projects to reconnect Center City to its waterfront.

Levy noted that daily traffic volume drops in half south of the Ben Franklin Bridge. The latest numbers from PennDot bear that out:

I-95 traffic between:

Girard Avenue and I-676 180,000 vehicles a day

I-676 and Walt Whitman Bridge 92,000 vehicles a day

Walt Whitman and Broad Street 114,000 vehicles a day

Levy argued that I-95 could flow onto a retooled section of Columbus Blvd until the highway picks up again at Washington Avenue. Portland, Ore., Providence, R.I., and San Francisco, have all removed highways to gain access to the waterfront. In New York City, a grade-level West Side Highway meshes well with the new Hudson River esplanade.

Since Levy spoke, two casinos have been licensed for the waterfront that could add another 10,000 to 30,000 daily trips to the highway. Residents are worried about casino traffic clogging the neighborhoods, and I-95 looks more like a candidate for expansion than demolition.

New Ramps?

Two possible highway projects are in play: In South Philadelphia, the Foxwoods casino has offered to build a new ramp from southbound I-95 to Columbus Blvd. at Dickenson Street. This would feed cars to the casino without using city streets. No plans have yet been made for this ramp, and construction would likely be years away.

Near the future Sugarhouse casino in Fishtown, PennDot is about to redesign the Girard Avenue interchange, improving access from the highway to Girard, Aramingo and Delaware avenues at a cost of $350 million. The project predates casino plans, but should aid access. PennDot officials say construction is likely to begin in 2009 and continue until 2014.

More info on PennDot’s Girard Avenue Interchange project can be found at: http://www.95revive.com/GIR/gir_main.cfm

Levy, too, worries about casino traffic. Yet he believes radical reconfiguration is an option worth exploring for portions of I-95 south of the Ben Franklin Bridge.

“There’s a lot of emotion focused around the casinos, understandably, but we really need to do some long-range thinking,” he said. “Someone has got to step back and make the broad analysis. If you take all the lanes of I-95 and all the lanes of Columbus Blvd, I think it’s 16 lanes. Do we need that many?”

Ideas to improve elevated portions of I-95

Outside Center City, I-95 generally runs on concrete legs about two stories above the city. Demolishing the heavily trafficked road, or sinking it into a tunnel or trench, are expensive and unlikely. But elevated highways can be reformed. On the Lower East Side of Manhattan, the firm of architect Richard Rogers recently devised a number of eye-catching improvements to civilize the elevated FDR Drive by re-cladding the underside, adding a snazzy lighting scheme and building pavilions beneath the road. The effect is striking. View the East River Waterfront Study for Manhattan at http://www.nyc.gov/html/dcp/html/erw/index.shtml

Building parks in the shadow of I-95

In Louisville, Kentucky, a 55-acre wasteland of industrial properties has been transformed into an award-winning public space, the Louisville Waterfront Park. The park features rolling lawns, playgrounds, water fountains and paths that slope down to the Ohio River – even though a tangle of highways snakes overhead. Check out the design at: http://www.pps.org/great_public_spaces/one?public_place_id=583

Then check out the sort of development the park has attracted at: http://www.waterfrontparkplace.com/

Other resources:

Read Steve Anderson’s full article at www.phillyroads.com/roads/delaware/

Photos of I-95 construction from the 1970s are at http://www.pennways.com/I95_PA.html

Matt Blanchard is a former reporter for The Philadelphia Inquirer who now teaches at the University of the Arts

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.