His father was the 1st Pa. inmate to die of COVID-19. Now, he’ll continue the fight to ‘clear his name’

The Pennsylvania Innocence Project concluded Rudolph Sutton was likely innocent, just as his health began to decline after serving 30 years behind bars.

Listen 2:21

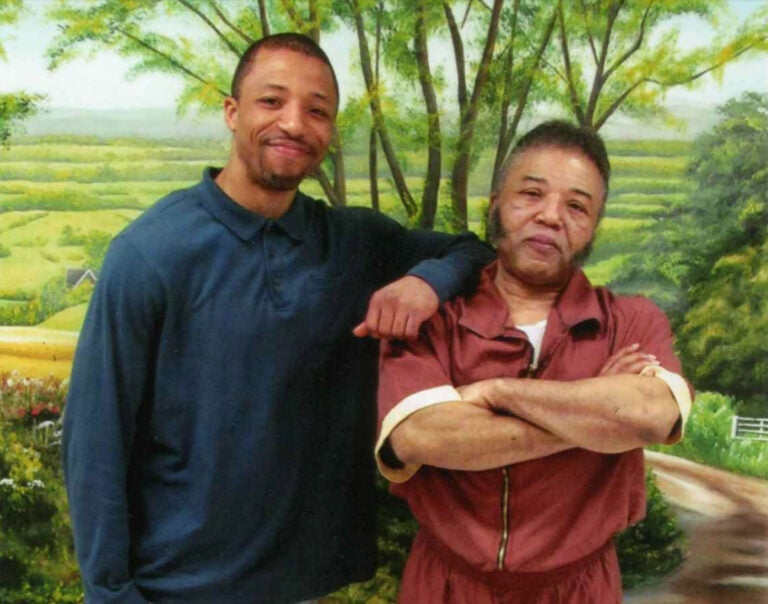

Rudolph Sutton poses with his son Rudolpho in a photo taken in 2015 at SCI-Graterford in Montgomery County, where Sutton was serving a life sentence. (Courtesy of Rudolpho Sutton)

Rudolpho Sutton’s thoughts are mired in a simple, but painful question about his father’s death: What happened?

On April 8, about a week after the Pennsylvania Department of Corrections announced its first prisoner had tested positive for the coronavirus, Rudolph Sutton was found unresponsive inside his cell at SCI Phoenix in Montgomery County, the state prison where he was serving a life sentence for a murder advocates say he likely did not commit.

A county coroner later determined the 67-year-old died from pneumonia caused by COVID-19, a revelation that made him the first — and currently the only — state prisoner to die from the virus.

Rudolpho Sutton, 37, wants to know whether that dubious distinction was avoidable — if prison officials did everything they could to try to keep his father alive.

“I’m not getting any answers,” he said.

Rudolph Sutton’s health started to decline in early March, and he spent 10 days in the hospital. His son still doesn’t know why, but he knows his father’s health grew worse after returning to SCI Phoenix.

He said his father, who had high blood pressure and liver problems, had difficulty breathing, often pausing between sentences when the two talked on the phone.

His sense of smell was off too, and he had trouble tasting his food, he said.

A video chat session in late March made it clear to Rudolpho Sutton just how sick his father had become. A man who excelled at martial arts was now in a wheelchair, a face mask dangling around his neck.

“I have plenty of pictures from our time together and he looked nothing like that,” said Rudolpho Sutton.

Their last conversation was on April 6.

It was a struggle. By then, the father’s breathing was even more labored. At one point, Rudolph Sutton’s voice cut out mid-sentence.

“I thought he died right on the phone,” said Rudolpho Sutton.

Two days later, his father was pronounced dead at Einstein Medical Center in East Norriton.

Rudolpho Sutton said he never assumed COVID-19 was to blame. His father was never tested. It wasn’t until the county coroner called that he knew what killed him.

“He didn’t belong there,” Rudolpho Sutton said of his father’s 30 years in prison. “That’s what makes this even worse,” he said.

Citing federal privacy law, a spokeswoman for the state Department of Corrections declined to provide details from Rudolph Sutton’s medical file.

Just as Rudolph Sutton’s health began to fail, the Pennsylvania Innocence Project was completing its five-year investigation into his 1990 murder conviction for the fatal stabbing of 33-year-old Dewey Mackey in South Philadelphia.

The nonprofit determined that Rudolph Sutton and his co-defendants were likely innocent, and reached out to the conviction integrity unit of the Philadelphia District Attorney’s Office to share their findings.

At trial, prosecutors maintained that Rudolph Sutton paid a group of men to to carry out the murder after Mackey allegedly sold some “bad” crack.

Attorneys with the Innocence Project have serious doubts about that narrative, concluding instead that the murder was more likely rooted in a feud between two Jamaican drug gangs, to which none of the convicted men belonged.

The case’s key witness did not mention Rudolph Sutton or any of his co-defendants when he first spoke with police.

“He named entirely other people the first time and it’s only after he then talked to detectives again and again that he starts bringing in these guys,” said Nilam Sanghvi, legal director for the Pennsylvania Innocence Project, referring to Rudolph Sutton and his co-defendants.

The District Attorney’s Office declined to confirm whether it’s looking into the case, a commitment that could prove critical to the Innocence Project’s effort to exonerate Rudolph Sutton.

‘Clear his name’

Rudolpho Sutton said he’s more determined than ever to clear his father’s name, even if it has to happen posthumously.

The two were “inseparable,” speaking on the phone several times a week, sometimes two or three times a day. Before the pandemic shut down in-person prison visits, Rudolpho Sutton drove from his home in Collingdale in Delaware County to the prison in Collegeville as much as possible, often once a week.

The conversations were easy, even though they went years without speaking to one another. After Rudolph Sutton was convicted, Rudolpho said his mother cut his father off from his eight children.

Rudolph last spoke to his father when he was six years old. They didn’t reconnect until he was 21.

“I was looking for it to be awkward and it wasn’t there,” he said. “We shared a common interest in literally everything.”

Most of all, they both loved to learn. Before he was arrested for Mackey’s murder, Rudolph Sutton had plans to transfer to Temple University after completeing courses at the Community College of Philadelphia.

Rudolpho Sutton now hopes to turn their mutual passion for learning into getting some answers about how his father died.

Rudolpho also hired a lawyer to plumb the possibility of bringing a wrongful death lawsuit against the Pennsylvania Department of Corrections, a process that could take months.

Under normal circumstances, collecting evidence from the state’s prison system takes time. A global pandemic could easily prolong that process.

“Our plan and intention is to conduct as thorough an investigation as possible concerning the circumstances surrounding Mr. Sutton’s death. Once we complete that investigation, we’ll make decisions about what course of action to follow,” said Jon Feinberg, the attorney reviewing the case.

For Rudolpho Sutton, it’s all part of his mission to set the record straight and to help exonerate his father.

“After the amount of time he waited and everything we put into this case, I’d like to see it get overturned,” he said. “I’d like his innocence to be proven and for once and for all, clear his name.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

![CoronavirusPandemic_1024x512[1]](https://whyy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/CoronavirusPandemic_1024x5121-300x150.jpg)