Heroin overdose shakes La Salle University into action

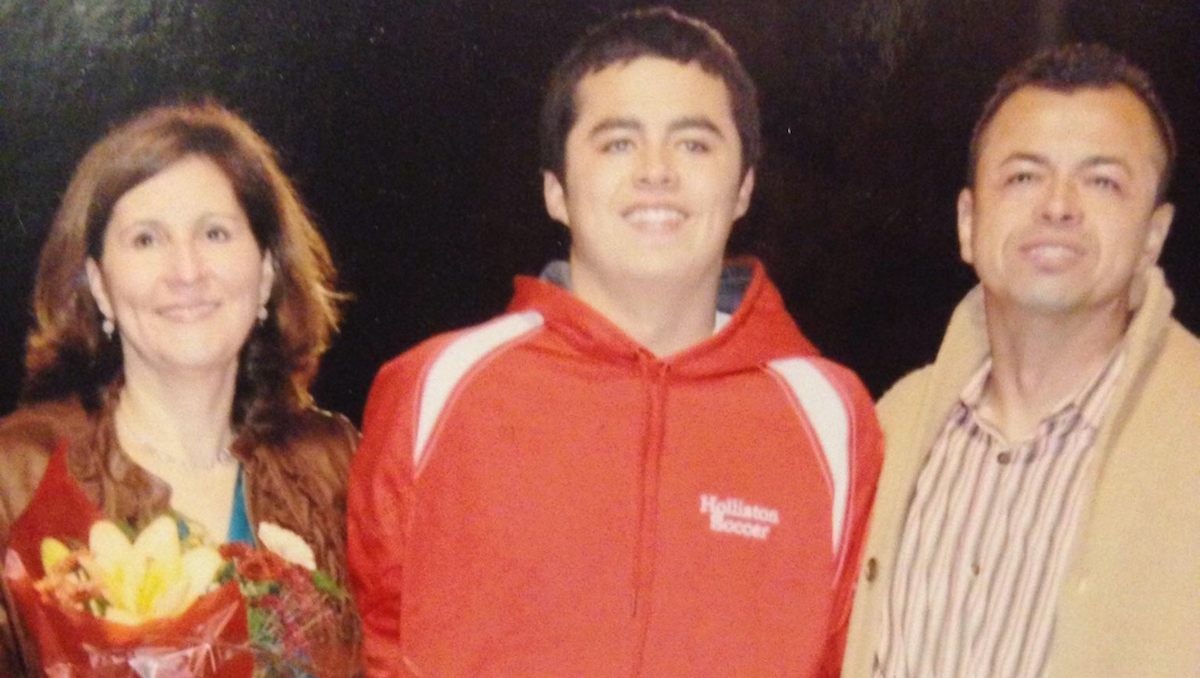

Joe with his parents

By all appearances, Jhoseph Ramirez-Brodeur was a well-adjusted digital arts major at La Salle University. Athletic and handsome, he loved soccer, made his own pasta and designed.

So it came as a shock to his family and friends when Ramirez-Brodeur, 20, was found dead from a heroin overdose in his apartment just off the La Salle campus in Northwest Philadelphia in May 2014.

“I just couldn’t believe it,” said his mother, Suzanne Brodeur. “How did I miss the signal?”

The fatal overdose, which shook the La Salle community, is part of a troubling trend among college-age youth across the country. Over the past decade, heroin use among 18-to-25- year-olds has more than doubled nationwide, according to a recent report by nonprofit Trust for America’s Health.

In 2011-2013, there were 7.3 heroin users per 100,000 college-age youth, up from 3.5 in 2002-04. The report attributed the increase to a rise in the misuse of prescription drugs.

While the rates of heroin use are rising among young people, the absolute number of users is still small, according to self-reported data in an annual health survey conducted by the American College Health Association. In last year’s survey, for instance, 10 of a representative sample of La Salle’s more than 4,300 students reported they had used heroin in the past 30 days. However, 46 percent said they believed other students had used heroin.

Brodeur said she had no idea her son was using any kind of opioid drugs, whether pain killers or heroin.

“I don’t know if he had done it before or he was just getting into it,” she said. “We never found needles, we never found drugs. I don’t know if it was a one-time thing.”

Brodeur spoke during an interview in late 2015, the first time she has publicly discussed the cause of her son’s death. She agreed to the interview in hopes that her son’s story would help alert others to the dangers of heroin and encourage them to “take a different path or think twice about it.”

She added: “No one should go through the pain of losing a child.”

Fatal overdoses at new high

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control reported in December 2015 that fatal drug overdoses, most of them due to pain killers or heroin, reached a new high in 2014 when they killed almost 50,000 Americans, more than died in auto accidents.

Among young men aged 19 to 25, Pennsylvania led the nation in fatal drug overdoses in 2011-2013, according to the Trust for America’s Health. In that demographic, the state had 30.4 overdose deaths per 100,000 residents, more than twice the national rate of 18.2.

Experts can’t explain why young men in Pennsylvania should be at any more risk than those in other states. But college officials, including those at La Salle, are well aware of the path that can lead young people from prescription pain medication to heroin addiction.

“Students go in for wisdom teeth extraction and they walk out with a prescription for 10 days of OxyContin or Percocet,” said Kate Ward-Gaus, director of La Salle’s Alcohol and Other Drug Education Center. “Once you’re done with your own prescription for opioids and you’re buying it on the street, it’s expensive. Heroin is only $10 a bag. It’s cheaper.”

Chasing the dragon

Vincent Nowakowski, a sergeant at the 35th Police District near La Salle, has seen his share of drug users during his 15 years as a narcotics expert on the police force. “Heroin is coming back because people are chasing the dragon,” he said. “They use for the first time and want that high again.”

Nowakowski said there’s also been a shift in how heroin is consumed. Instead of injecting, users are now ingesting or inhaling the drug. Heroin is also now being combined with fentanyl, an analgesic that is more potent than morphine. Users may not know that their heroin has been mixed with another drug.

“When I arrive on the scene of an overdose, I can’t help but think, ‘why?'” Nowakowski said. “We need to educate people on the dangers of drugs.”

La Salle began stepping up its education program about the dangers of pain medication and heroin in January 2014. “What the drum needs to be banged about is prescription pain medication,” said Ward-Gaus. “Every student we’ve worked with who used heroin started with pain medication. They went to heroin because they couldn’t afford (prescription pain medication).”

Education cutting misuse

The university’s effort to communicate the dangers of misusing prescription painkillers seems to be paying off. In the 2015 survey by the American College Health Association, just 4 percent of La Salle students reported they had taken pain medication that was not prescribed to them. The figure was down from 6 percent in 2011. Ward-Gaus said she would “like to think” the school’s education program has made a difference.

In addition to steering students away from the misuse of prescription pain killers, Ward-Gaus also wants students to know that drug addiction is treatable.

“You can get out of addiction,” she said.

While La Salle has its own counseling services, it also refers students to treatment programs in the community.

Brodeur wants to see more young people reach out to some of those programs. “You have the ability to check yourself into the hospital without anyone knowing,” she said. “I understand if people are afraid to go to their parents, but there are other avenues, especially with so much data and research out there.”

A ‘fundamental tragedy’

Brodeur said parents need to recognize that losing a child to heroin is no different from losing a child for any other reason.

“When you lose a child, you lose a child,” she said. “It really doesn’t matter how it happened, whether it’s a car, whether it’s an accident, or a plane comes down and hits them. It’s such a fundamental tragedy that, at the end of the day, it’s the same pain but getting there is different.”

While the pain of her son’s death is always with her, Brodeur also celebrates his life.

A native of Colombia, Ramirez-Brodeur grew up in Holliston, Mass. where he played soccer, basketball, baseball and football. At 12, he gravitated to soccer and went on to play club and Division 1, traveling throughout the country.

“It seems like every family party at his house eventually turned into a soccer game since he, his sister, and his father all loved to play,” said his younger cousin, Audrey Renee Brodeur.

Ramirez-Brodeur was proud of his Latino heritage, so much so that he celebrated it when he graduated from high school.

“I remember him giving a speech in Spanish at his high school graduation party about how much it meant to him to be Colombian and how grateful he was to be part of his family,” his cousin added.

Cooking with mom

An amateur chef, Ramirez-Brodeur took part in a cooking contest at La Salle. “He often explored new recipes from all countries and made homemade pasta. We had attended French cooking classes together,” his mother said.

Brodeur said the family always talked openly with their son about the challenges that often come with young adulthood. “We talked to him a lot about drugs, alcohol, relationships….We didn’t see any indications of (heroin). And talking to his close friends, none of them knew.”

But during the last week of her son’s life, Brodeur sensed that “something wasn’t right” with her son. “He had texted me when I was in a meeting,” she said. “I tried to [reach] him that night but I couldn’t [reach] him. I was worried by the morning.”

La Salle security found Ramirez-Brodeur’s body in his apartment in the 5300 block of Chew Avenue.

“You really have to understand that (drugs are) dangerous and the best option is not to start at all,” Brodeur said. “Every day I wish that Joe would have thought twice about going down that path.”

Germantown Beat is a website produced by student journalists at La Salle University.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.