A guide to understanding Violet Oakley’s Pennsylvania Capitol murals

In 1911, muralist Violet Oakley landed a commission unlike any given to an American woman at that time. But according to the Pennsylvania Capitol Preservation Committee (CPC), the resulting press would anger her for years: many reporters claimed that the images about to transform the Pennsylvania Capitol were not Oakley’s own.

Oakley was born in New Jersey in 1874, painted throughout the world, and lived in Philadelphia, in Mt. Airy, for most of her life. When she began her work for the Capitol in 1902, in her suburban Philadelphia studio, she was in her late twenties. She had no idea it was the start of a 25-year magnum opus.

Architect Joseph Huston was designing Pennsylvania’s new Capitol, and famed illustrator Edwin Austin Abbey (born in Philadelphia in 1852) clinched the commission to decorate the building’s massive rotunda, as well as its House, Senate, and Supreme Court chambers. Architect John Irwin Bright, a mutual friend of Huston and Oakley, recommended the young woman for the murals of the Governor’s Reception Room.

The Preservation Committee quotes Huston as saying that Oakley’s work would “add interest to the building and act as an encouragement of women of the state.”

Oakley’s research took her straight to England, despite existing artistic recommendations from Huston and Governor Pennypacker. Her 14 murals, collectively titled “The Founding of the State of Liberty Spiritual”, were installed and unveiled in 1906. They are a theological and political history, and none of the figures in them stands on Pennsylvania soil.

Paintings in the Governor’s Reception Room

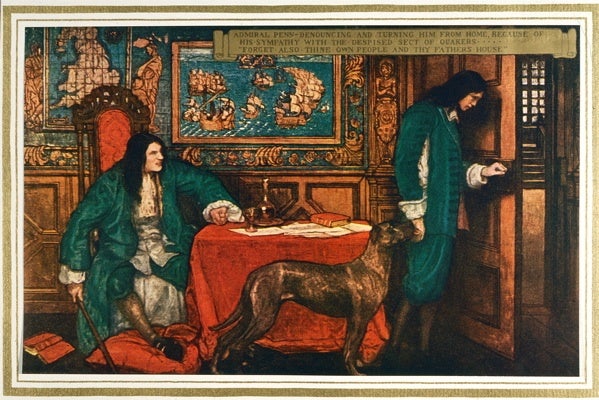

The images begin in the sixteenth century with the persecutions of William Tyndale, who dared to translate the Bible into English. Later, Protestant firebrand Anne Askew also meets her death in 1546. Quakerism founder George Fox appears, arms spread wide against a mysterious ocean storm, and gives way to dramatic tableaux in the life of William Penn, from dreamy days at Oxford to a ship bound for America. Throughout, Oakley aimed to glorify the principles of religious tolerance and social justice that were Penn’s dream for Pennsylvania.

Preservation Committee Historian Jason Wilson notes that Oakley deliberately avoided depicting any US-based historical scenes that Abbey would have already had in hand for the other chambers.

But just as Abbey’s work on the House chamber was completed, he died suddenly of cancer.

Oakley’s responsibilities expand

Capitol officials pleased by Oakley’s work in the Reception Room saw her as a natural choice to take up Abbey’s commission, offering her the same amount of money in Abbey’s old contract (although not adjusted for inflation): $50 per square foot of mural.

Oakley began her new commission by searching for her predecessor’s plans – she even wrote to his widow – but found none. So she undertook her own designs, but for years faced reporters who declared that she was executing sketches done by Abbey, instead of seeing her as an artist in her own right.

The Senate chamber

The centerpiece of Oakley’s Senate murals, “International Unity and Understanding”, a 44-foot long visual epic, features swords beaten into ploughshares at left and Dante himself handing symbolic “fruits of culture” to the masses at right. Arms outstretched, dominating the middle, a massive Madonna-like figure wears a dramatic blue gown that becomes the waters of life.

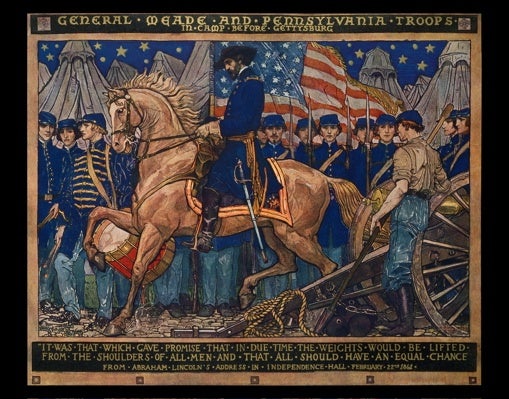

Other Senate panels include a poignantly boyish depiction of Gettysburg troops under General George Meade, the Gettysburg Address, and cautionary images of armies and slave-drivers who would subvert freedom and justice. Last installed were two panels depicting Quaker legends (Oakley, herself an active Christian Scientist, was also enamored of Quaker beliefs).

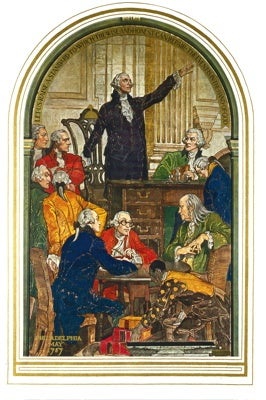

Wilson has a small bone to pick with other scholars when it comes to another of Oakley’s Senate murals. Conventional wisdom says the picture shows Pennsylvania’s 1787 Constitutional Convention delegates. But Wilson contends that one of the figures in the painting may be Alexander Hamilton of New York. Why would Oakley have included him? But most interesting of all, Oakley pointedly includes a subservient African-American figure in the foreground, lifting the delegates’ heavy books. He reminds us that it took a long time for freedom to extend to all.

The night before the Senate murals were dedicated in a 1917 ceremony (on Lincoln’s birthday), the Governor feted Oakley with a dinner at his mansion. But during the ceremony, there was a massive glitch: he tugged and broke the cord meant to pull the curtain from “Unity”.

Wilson describes how a staffer scaled a 40-foot ladder and crawled along the chamber cornice, pulling the curtain away by hand in front of the crowd.

Oakley quipped that it must mean the world wasn’t ready for peace. Two months later, the US would enter WW I.

The Preservation Committee’s 2002 book on Oakley, “A Sacred Challenge”, documents a threat to Oakley’s Senate design, just in time for WW II. In 1943, Senator John McKreesh launched an unsuccessful campaign to paint out the image of the Japanese flag, which was included alongside many other flags in one of the murals.

The Supreme Court

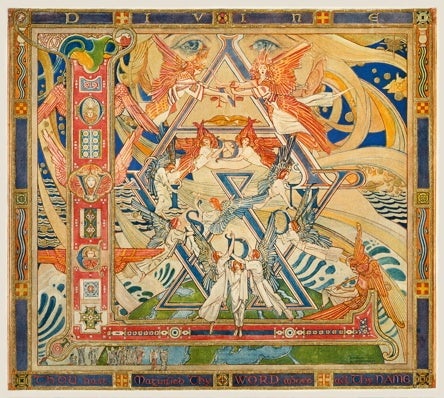

When Oakley began her work on the Supreme Court chamber in 1920, she was 46 years old. Highly allegorical and full of ornate text, these murals trace Oakley’s concept of the development of law, from the laws of nature likened to musical notes on a scale, through the Beatitudes, Justinian, and The Hague. In a picture of thinkers from Locke to Rousseau, you can just see Oakley herself, in the top left corner.

By 1927, when the Supreme Court murals were installed, the commission had earned Oakley $95,000.

The trailblazing artist died in 1961. By the time the Preservation Committee (formed in 1982) launched a restoration of the murals, water leaks had caused severe damage. From 1992-1994, with an ample restoration team, the Committee saved all 43 of Oakley’s Capitol murals, from Charles II in the Reception Room to Hobbes in the Supreme Court chamber.

But Wilson, a 12-year member of the Committee, is dismayed by recent drastic cuts to his office’s annual budgets. Now, a single staff preservationist is responsible for the Capitol’s 640 rooms.

As some of the nation’s most contentious political debates roil modern-day Pennsylvania, the figures watching over our court and legislators disavow partisanship and strife – one of many reasons Oakley’s work should endure.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.