Gentrification property tax relief — for whom?

Philadelphia’s proposed $20 million/year of gentrification property tax relief, the Longtime Owner Occupants Program, fails to target the most deserving low-income residents and may even make the local tax system more regressive.

The city council bill defines gentrification as a 300-percent increase in property value (after deducting the homeowner exemption). This seems like a lot until you realize that most properties were undervalued at 34 percent of market value — so the city is giving out gentrification relief to any property with an above-average increase in value. If it were not for the homeowner exemption, this broad definition would include half of the residential properties in the city.

Benefit to low-income residents cannibalized by the rich

The means test — to decide if a resident deserves gentrification tax relief based on their income — is even more questionable. Philadelphia is using the HUD definition of median household income and applying a test to include only households that are under 150 percent of that number. Unfortunately the HUD pools Philadelphia with our wealthier suburbs and derives a median household income of $81,500. This is more than twice the figure for Philadelphia county: $37,000. This HUD value is completely unrelated to the cost of housing or living in Philadelphia.

The actual means test limits are

$83,200 for one person

$95,050 for two people

$106,950 for three people

$118,800 for four people

And so on (add $9,500 for each additional person over four).

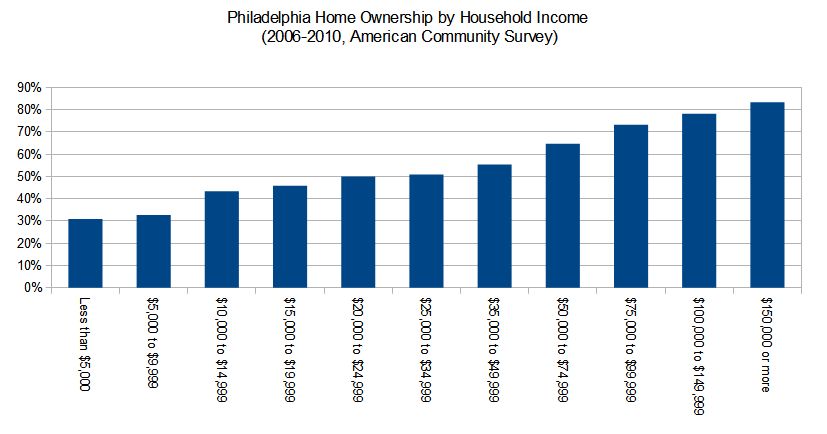

What this means is that approximately 87 percent of Philadelphia households*, including most of the upper-middle class, will meet the means test for gentrification relief. Only 12.7 percent of Philadelphia households make more than $100,000 per year.

The cost of the bill is limited to $20 million per year. If the demand for the money exceeds that amount, then homeowners will receive only partial relief. In practice, this means that the money going to the upper-middle class could reduce the relief for low-income people. Even if the bill’s budget is not exceeded, the money could be better targeted to providing relief to low-income taxpayers or better spent funding schools.

Upper-middle-class households are likely to have homes higher in value than those of low-income households and thus receive larger tax breaks from gentrification relief. Factoring in the homestead exemption excludes more low-income households from getting relief than higher-income households.

The correlation between income and house value is modest: 0.52 for Philadelphia (according to Census PUMS data and my analysis). This means that 27 percent** of the house value can be explained by a household’s income. Richer people are likely to have higher-valued houses than low-income people. It also means that 73 percent of property tax is not related to current income, and that makes it a very regressive tax.

Renters lose out

People with relatively low incomes are more likely to rent. Long-time renters do not qualify for gentrification relief, but they will pay higher rents when landlords pass on the cost of increased property tax. Low-income renters already face increasing rents because of Philadelphia’s citywide Actual Value Initiative lacks a homestead exemption for renters. Gentrification relief makes things worse by increasing the property tax base rate.

Low-income home owners are less likely than higher-income home owners to have owned their homes for 10 or more years and thus are less likely to qualify.

People who qualify for gentrification relief are likely to have lower taxes than those who do not, as their property value is locked in for 10 years. Non-gentrified property valuations will increase over the long run — probably at the rate of inflation. In the 10th year, it is likely that non-gentrified properties will be worth (and taxed) 20 percent to 25 percent more (assuming a 2 percent rate of inflation).

Solution: fairness

In the short term, the city should replace the HUD median household income with the Philadelphia County one. The value of gentrified properties should increase each year at the rate of inflation (or the same rate as Philadelphia property prices).

In the long term, we need to replace residential property tax with a less regressive tax. We need to replace our local and state regressive taxes with progressive ones that tax people based on their ability to pay and reduce economic inequality.

—

* This is an estimate based on the percent of Philadelphia households that earn under $100,000, and the mean Philadelphia household size of 2.53. The mean household size makes the average means test around $100,000 for most households (with larger households who have a higher means test cancelling out smaller ones with a lower means test).

** The figure 27 percent is the square of 0.52, i.e., 0.522 = 0.2704. It is a statistical relationship “bivariate analysis.” I first got the correlation of the two variables and then the R2 (or percent of explained variance) is the square of the correlation coefficient.

—

Aaron Kreider, originally from Vancouver, British Columbia, has lived in West Philadelphia since 2002. Currently he works as a web developer for an environmental organization. He has a masters in sociology from the University of Notre Dame. His love for statistics started at age 11 with reading almanacs.

—

CORRECTION: A previous version of this essay indicated that there were age restrictions to the gentrificaiton relief program. There are income limits, but there are no age restrictions. Also, the author implied that the program considers the income for every person in a multi-unit property. However, only the owner’s household income is considered (which does include rent received by the owner). The income of tenants should not be included when entering the household income on the application.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

Click to enlarge

Click to enlarge