Frightening facts parents should know about teens and binge drinking

Studies are accumulating showing the teen brain, consistently plied with alcohol, won’t reach maturity and damaged genetic material may be passed on.

Studies are accumulating showing the teen brain, consistently plied with alcohol, won’t reach maturity and damaged genetic material may be passed on. (Oswaze/BigStock)

How do we help children thrive and stay healthy in today’s world? Check out our Modern Kids series for more stories.

When your little ones misbehave, you might send them off for timeout. As they get bigger, maybe you cut back their gaming time — or cut it off for a while.

But when those children become teenagers and the offense is drinking, grounding them probably isn’t going to work.

“Sometimes, really strong language can make the problem worse,” said Aaron White, senior scientific adviser to the director at the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

Because irrationality rules teen behavior — the prefrontal cortex, the part of the brain that guides rational decision-making, doesn’t fully develop until a person hits 25 or so — reasoning with teenagers isn’t going to persuade them that drinking is ill-advised, let alone hazardous to their health.

But the elements of danger are there, all right, visible in national survey data, obvious in psychiatrists’ and psychotherapists’ offices, on point in biochemistry labs and underlying numerous clinical trials.

Binge drinking, especially, can’t be blown off as an adolescent adventure with no consequences.

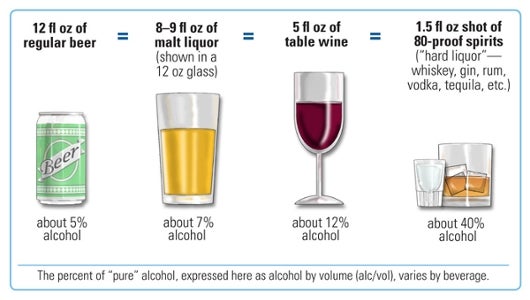

In adults, bingeing means becoming legally drunk in two hours. But an adult’s average weight is at least 70 pounds more than that of a 13-year-old, whose average weight is 100 pounds, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. For many teens, that means it takes less alcohol for them to become legally intoxicated. (This weight chart indicates how alcohol affects a drinker, by weight and number of drinks.)

Researchers define “dangerous drinking” as multiple episodes of bingeing in a single month.

Studies are accumulating that show the teenage brain, consistently plied with alcohol, will not reach maturity; that its owner will likely die earlier than nature intended; and that, if the young person ever has children, damaged genetic material could be passed on to them. Researchers believe that at least 50% of alcohol use disorder is passed from generation to generation. And new research strengthens the genetic connection between alcoholism and decision-making processes involving drinking.

“Alcohol is a dirty drug,” said Gene-Jack Wang, a physician researcher with the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

What alcohol does to the body

“Dirty” because alcohol affects so many things — the liver, certainly, whose job is to detoxify chemicals and metabolize drugs in the body — but even how the brain feeds itself.

Normally, the brain’s energy source is glucose. But when alcohol begins to break down, the brain will switch its food source to acetate, one of alcohol’s byproducts. “That is why there is withdrawal, and it induces inflammation,” Wang said.

“It impacts the whole genome,” said Subhash Pandey, a professor and director of the Alcohol Research Center at the University of Illinois at Chicago. (A genome carries every protein that will be replicated in an organism.)

In September, Pandey and colleagues published research that discusses the damage alcohol does to important chemicals needed in the development of memory, mood, intelligence and more. It’s harm that can follow a teen into adulthood. The researchers located the molecules that affect increased anxiety and alcohol use in adults because these molecules were changed during adolescent development.

Pandey has studied chromatin, without which normal cell development doesn’t happen, because its job is to protect DNA from damage. Pandey’s animal studies have shown that animals born to mothers who drink have condensed chromatin.

“If someone is born with condensed chromatin, maybe they are prone to anxiety, and they drink to self-medicate,” he said.

Alcohol also can do serious damage to neurotransmitters like serotonin. Healthy serotonin levels maintain mood balance.

Since 1971, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration has issued an annual study called the National Survey on Drug Use and Health. About 70,000 people, ages 12 and up, are randomly selected to participate. The data is then extrapolated to represent the U.S. population.

Findings from the 2016, 2017 and 2018 surveys indicated that though the percentages varied a bit from year to year, growing segments of the U.S. preteen and young teen population were engaged in dangerous drinking. (The survey defines preteen as 12 and 13 years old.)

Alcohol and thoughts of suicide

The dangers observed in psychiatrists’ and psychotherapists’ offices are the increased cases of depression and those patients’ accompanying suicidal thoughts. Data from the national survey bears this out, expressed in young respondents’ statements that their own suicidal thoughts were fueled by alcohol or another substance.

“We are seeing a trend, and it’s concerning,” said family psychologist and WHYY contributor Dan Gottlieb.

Binge drinking poisons the brain, said physician Christopher Cutter, an assistant professor at the Yale School of Medicine and chief of adolescent psychology at Turnbridge, an addiction treatment center.

Bingeing, Cutter said, affects motor skills, problem-solving skills and memory, and then, because those brain sections aren’t being used properly, it causes them to shrivel up. The trends seen at his center include more eighth-grade girls with drinking problems, he said, along with male high school seniors.

The girls are quite a bit ahead of the boys in eighth grade. “By 12th grade, white males overrun everybody,” Cutter said.

Other recent research, in which the genomes of thousands of European American and African American families were analyzed, found matching genetic material that the researchers traced to dependence on alcohol, such as desire to cut down on drinking, drinking more than intended, and time spent drinking.

Are the numbers huge? No.

Does that matter? No, said Gottlieb.

“Broaden it out to life for these kids,” he said. “Depression is increasing, and suicide is increasing. We are seeing disease among our youth.”

Data from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health showed figures in some categories going down, such as overall lifetime numbers regarding alcohol use by 12- to 17-year-olds. In the 2018 survey, alcohol use decreased to 6,551,000, from 6,765,000.

Yet Joseph Lee, medical director of Hazelden Betty Ford Youth Services in suburban Minneapolis, and others aren’t particularly elated. You need to look at risk factors, like the family’s involvement with alcohol, he said.

“The kids who are at high risk [with alcoholics in the family, for example] are different,” Lee said, noting that the data is “a mixed bag.”

Overall, it looks as if substance use is going down, Lee said, but issues like drug overdose are increasing. High-risk youngsters — those who live with alcoholics, have problems in school, cannot relate with others, have discipline issues — they are involved with the excessive use, with the mental health issues.

“These things are related,” he said.

The 2016-2017 study showed that for the 12-to-17 age group, about 200,000 more teens (3.2 million, up from 3 million) had serious episodes of depression: Their weight changed; their sleeping habits changed; they considered suicide. Adding a drug dependency, the group that had at least one such episode went from 333,000 to 345,000.

Alcohol and behavior

In the 2016-2017 study, representatives of every age group between 12 and 17 either fought at work or school, became involved in a group-on-group fight, or attacked someone with intent to injure.

The biggest increases were among the 16- and 17-year-olds. It is not known whether these youngsters were binge drinking at the time of the fighting.

By the 2018 study, the 15-and-under set still were fighting — figures for the 12- to 13-year-olds jumped from 331,000 to 391,000.

All groups also stole more property in the earlier study. In the 2018 study, theft had dropped — but the preteens had started carrying guns.

“Culturally, our young people mimic our social discourse, in a caricature kind of way,” Lee said.

Not all teenagers drink, of course — even if it seems everyone around them is.

Nicholas Garvey, 18, who now goes to Hamilton College in Clinton, New York, doesn’t. He’s a Denver native who says his high school, a charter school with scientific and tech leanings, was small enough that everyone in his class of 120 year knew everyone else.

“The radicals started in freshman year,” he said. “By junior year, it was more difficult to find those who did not partake.”

Alcohol was lower on the list of party tools; marijuana and vaping were the “larger thing,” Garvey said. Even before marijuana was legalized in Colorado in 2012, “it was definitely there. Now, [legalization] has normalized it.”

He sees no reason to drink, a decision he said was affirmed at a party where he witnessed his classmates’ reactions to smoking marijuana.

“Everybody was melting into the couch, and I was really bored,” Garvey said. “I went home.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.