Fracking needs oversight

Advocates of the extraction process known as “fracking” say it’s safe, yielding vast quantities of natural gas without polluting our land and water. So, they say, federal environmental regulators should back off.

And that, my friends, is what philosophers call a non sequitur. Let’s hope it’s a nonstarter, too.

Fracking, short for hydraulic fracturing, involves pumping chemical—and sand-laden water deep into the ground to break up rock formations and release gas. If it’s as safe as its supporters say it is, they should welcome federal oversight. Their very resistance to scrutiny suggests it might not be so safe after all.

Consider the FRAC Act, cosponsored by Sen. Bob Casey (D., Pa.), which would allow the federal Environmental Protection Agency to regulate the chemicals gas drillers use. The bill has sparked outrage within the industry and the Republican Party, whose leaders seem to be trying to outdo each other in condemning the EPA.

Rep. Michele Bachmann, for example, has promised to padlock the EPA’s doors if she’s elected to the White House. Texas Gov. Rick Perry, the front-runner for the GOP nomination, pledges to impose a moratorium on all federal environmental regulation, saying it should be left to the states.

But here in Pennsylvania, state regulators have allowed natural-gas companies to discharge tainted waste water into rivers that supply drinking water to more than 16 million people. Although federal law requires drillers to know what waste they are producing and to treat it before releasing it into waterways, treatment plants in Pennsylvania have been dumping untold amounts of drillers’ mystery liquids.

That’s where the EPA comes in—or where it should. Thus far, the agency hasn’t stepped in to enforce the law. So we still don’t know what chemicals have been discharged or what they have done to our water supply.

But here’s what we do know: During the last big energy booms in Pennsylvania, in the 19th century, extraction industries wreaked havoc on the environment. We shouldn’t let that happen again.

The state’s first great energy resource was coal, which helped fuel the young nation’s industrial revolution. Since then, Pennsylvania has produced more tons of coal than any other state. But the coal industry also polluted nearly 2,500 miles of streams through so-called acid mine drainage, killing fish and plants. Nationwide, a third of the waters affected by acid mine drainage are in the Keystone State.

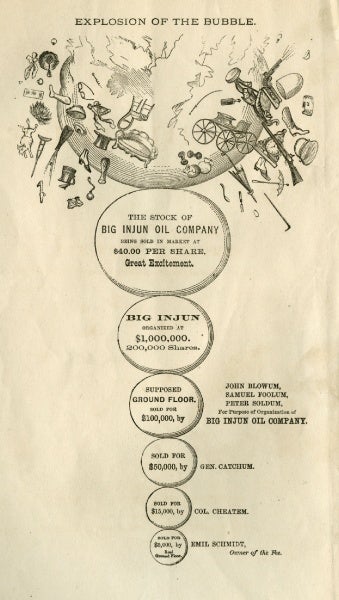

Pennsylvania was also the site of the world’s first intentionally drilled oil well, which started gushing in Titusville in 1859. So did hundreds of other wells in subsequent years, making the state the world’s largest producer of oil for about a decade. But one-third of the extracted crude leaked from skiffs into the state’s rivers, which frequently caught fire. On land, meanwhile, spilled oil soaked what it didn’t burn.

“The soil is black, being saturated with waste petroleum,” a journalist wrote in 1865, visiting aptly named Oil City. “The engine-houses, pumps, and tanks are black. … Even the trees wore the universally sooty covering. Their very leaves were black.”

Only the rise of state and federal environmental regulation stemmed the tide of filth and pollution. The key reform was the National Environmental Policy Act of 1970, which created the Environmental Protection Agency. It was signed by a Republican president, Richard Nixon, who called on Americans to “transform our land into what we want it to become.”

So what do we want our land to become? Yes, fracking promises to bring millions—if not billions—of new investment dollars to Pennsylvania. But, to paraphrase the Gospels, what good will it be for a state to gain the whole world if it loses its environment?

Industry representatives insist that fears about fracking are exaggerated, and further regulation would be unnecessary and costly. But the only way to determine the real effects of fracking is to empower regulators to find out. And that would be worth every penny.

Recalling her youth in Pennsylvania, the great muckraking journalist Ida Tarbell pronounced an angry epitaph for an earlier generation of polluters.

“No industry of man … has ever been more destructive of beauty, order, and decency than the production of petroleum,” Tarbell wrote. “Every tree, every shrub, every bit of grass in the vicinity was coated with black grease and left to die. … Nobody ever cleaned up in those days.”

One day, thanks to fracking, our children and grandchildren might write something similar about this era. And nobody wants that. Let’s clean up our own mess, then, before it’s too late.

“That’s History” is a biweekly radio segment co-produced by the Historical Society of Pennsylvania and WHYY featuring HSP historian Jonathan Zimmerman. Every two weeks we take an event, issue or person in the news, and look back into history for echoes, parallels, roots and lessons. Tune in to hear That’s History every other Tuesday at 6 p.m. on Newsworks Tonight on WHYY.

Jonathan Zimmerman can be reached at jlzimm@aol.com.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.