Finally, a movie about the Chappaquiddick scandal

When I heard that Hollywood was making a movie about Chappaquiddick, I said to myself, "Hallelujah. It's about time."

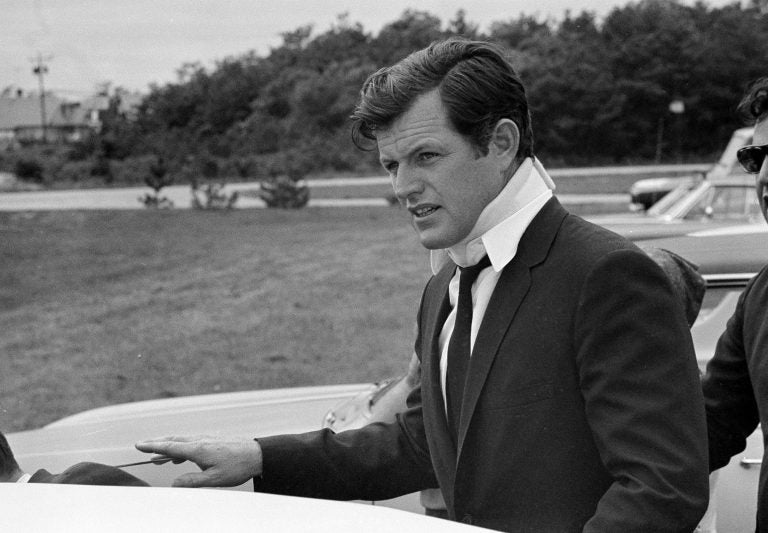

FILE-- This July 22, 1969 file photo shows U.S. Sen Edward Kennedy, D-Mass., arriving back at his home in Hyannis Port, Mass., after attending the funeral of Mary Jo Kopechne in Pennsylvania. A new feature film is in the works about the tragedy on the small Massachusetts island nearly a half century ago that rocked the Kennedy political dynasty. Kopechne drowned when a car driven by Kennedy went off a bridge on Chappaquiddick, a small island in Edgartown, Mass., on the eastern end of Martha's Vineyard in July 1969. (AP Photo/Frank C. Curtin, File)

When I heard that Hollywood was making a movie about Chappaquiddick, I said to myself, “Hallelujah. It’s about time.”

Why did it take so long? A prominent politician with presidential ambitions drives off a rickety bridge late at night and drowns a young woman, leaves the scene of the accident, fails to report it to police, huddles with his handlers to decide how best to spin the debacle, waits seven days before he goes public … that kind of script writes itself. How is it possible that nobody filmed it during a span of nearly 50 years?

Because Hollywood is predominantly liberal, and the Kennedys have many friends there.

There is no other explanation, and the evidence — while circumstantial — is overwhelming. There have been numerous movies and TV treatments of the Watergate scandal, featuring Richard Nixon as a tragic figure undone by his demons. There have been zero dramatizations of Chappaquiddick featuring Edward Kennedy as a tragic figure undone by his demons. Until now, nobody wanted to touch that third rail and risk getting burned by Hollywood powers who believe the Kennedys’ worst failings should be exempt from scrutiny.

Indeed, Bryon Allen, the executive producer of “Chappaquiddick” (in theaters starting this week), told Variety that he took some heat: “Unfortunately, there are some very powerful people who tried to put pressure on me not to release this movie. They went out of their way to try and influence me in a negative way. I made it very clear that I’m not about the right, I’m not about the left, I’m about the truth.”

Allen didn’t name names, but he didn’t need to. What he experienced was nothing new. It had happened before.

When the History Channel announced in 2010 that it was planning an eight-part dramatization called “The Kennedys,” Hollywood friends and allies of the family went ballistic. They put heat on the History Channel to kill the series; Ted Sorenson, a former JFK aide and one of the earliest Kennedy hagiographers, warned darkly that if the cable network didn’t surrender, “there will be hell to pay.” The censorship crusade was so intense that the network dumped the series. (It didn’t die, however. It was picked up by another cable network, Reelz, which aired it in 2011. Greg Kinnear played a great JFK.)

And when Byron Allen insists that he’s “not about the right, I’m not about the left, I’m about the truth” — well, good for him. The truth should supersede all ideological labels. The truth requires that Kennedys be scrutinized, warts and all. There is much to admire about the Kennedys; I support the issues that Ted Kennedy relentlessly fought for during his fine Senate career. But Kennedy flamekeepers have long sought to minimize the family’s dark side, and that is no longer sustainable. Not in this era, when the exploitation of women is a top-tier issue.

Allen refers to Mary Jo Kopechne as “one of the original #MeToo victims,” and that’s why this film fits the current zeitgeist. If Kennedy’s 1969 behavior had occurred in 2018, his Senate career would’ve crashed in an instant. Lest we forget, Al Franken’s Senate career crashed after he was outed for sins that were, by comparison, infinitesimal.

Kennedy’s sins on the night of July 18, 1969 — excuse me, his criminal and political offenses — are factually beyond dispute: A notorious cruiser of women, he did some drinking at a cottage party on Chappaquiddick Island. He drove off with Kopechne, who had worked for brother Bob’s ’68 presidential campaign. He later claimed he was driving her to the ferry that connected the island to Edgartown (where she had a hotel room), but the last ferry had left at least an hour before he took the wheel. And Kopechene had left her purse and room keys back at the cottage. The left-bending road to the ferry was paved; instead, Kennedy took a sharp right turn onto a dirt track that led to a wooden bridge that led to a deserted beach. He knew that route well; he had visited the beach during the day.

He never reached the beach. His car hit the water and flipped over. He escaped. After trying and failing to extricate Kopechne, he trudged back to the cottage. On the way, he passed a number of houses and an emergency fire station, but didn’t stop to report the accident. At the cottage, he told two of his flunkies (a cousin and a friend) about the accident. The three men returned to the scene and tried unsuccessfully to help Kopechne. Back at the cottage, none of them picked up the phone to call police. Instead, Kennedy swam the short distance to Edgartown and slept it off in his hotel room. He didn’t report the accident until after it was discovered 10 hours later. Ultimately, he pleaded guilty to leaving the scene of an accident. He received a suspended sentence and probation.

That’s the gist of what happened, though there was much more; Kennedy’s team of spinners and enablers overwhelmed the obsequious local authorities. Kennedy by that point in his Senate career was known for treating women like tissue, but he could do no wrong in Massachusetts; as the late great journalist Michael Kelly once quipped, “he’d have to hit the pope and pee on the Irish flag to lose his Senate seat.” He kept the seat until death did they part, in 2009. But the nagging questions about Kopechne’s death did kill his presidential ambitions; the scandal was baggage during his failed ’80 bid for the nomination.

So it’s long past time that Chappaquiddick has been plucked from the mists of history — for the benefit of an audience newly sensitized to the mistreatment of women, especially those in the audience not yet born in 1969. The existence of this new film is proof that Kennedy hagiography is on the wane, even in Hollywood. And rightly so, because the truth demands it.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.