Explainer: Positive Train Control and the Amtrak 188 derailment

Positive Train Control (PTC) would have prevented Amtrak 188 from derailing Tuesday, National Transportation Safety Board lead investigator Robert Sumwalt said this week.

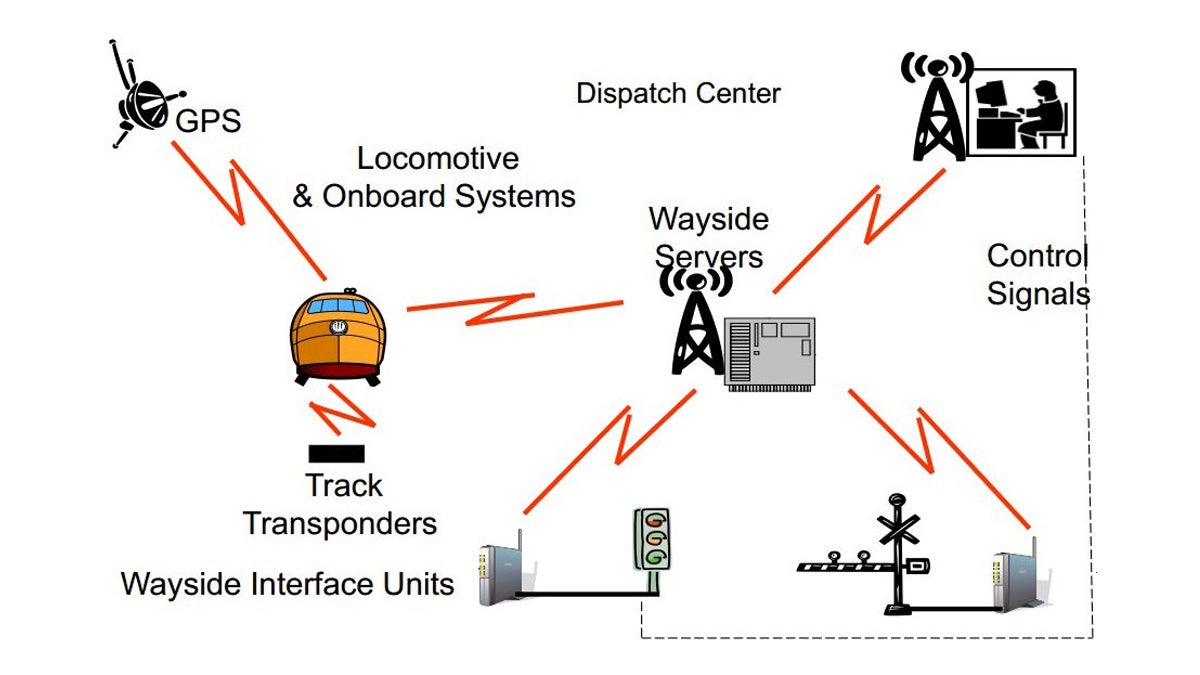

(Diagram courtesy of the Federal Rail Road Administration)

Positive Train Control (PTC) would have prevented Amtrak 188 from derailing Tuesday, National Transportation Safety Board lead investigator Robert Sumwalt said this week.

Amtrak was intending to install the safety system on the Northeast Corridor by the end of year, pursuant to an unfunded congressional mandate under the Rail Safety Improvement Act. Amtrak CEO Joseph Boardman has said that, with more funding, Amtrak could have implemented PTC sooner.

The stretch of the Northeast Corridor where the derailment occurred currently uses an older system, Automatic Train Control (ATC). On the southbound route, the ATC “enforces” — automatically stops — a train if it is travelling above 45 miles per hour. The northbound side, where Amtrak 188 was travelling, does not.

PTC is essentially a smarter version of ATC. Whereas ATC relies on the signal and fixed block system trains have operated on for decades, PTC uses a GPS and radio technology to locate where the trains are along the track. ATC only knows when a train trips a signal wire entering into another large stretch between interlockings or rail crossovers — it’s like knowing when someone entered a long hallway and when they exited, but not having any idea where they are within the hallway. PTC would let you know exactly where the train was and exactly how fast it was going.

In both systems, if the train exceeds the speed limits for a portion of track, warning signals sound in the engine’s cab. If the engineer fails to reduce speed, then an automatic brake will apply.

PTC allows for any speed limit to be enforced along the route. Between 30th Street Station and the site of the derailment, the speed limit changes eight times, going up to 80 miles per hour, then down to 60 miles per hour, then back up to 80 miles per hour again, before dropping to 50 miles per hour entering the curve where the crash happened. PTC would have been able to enforce all of those speeds.

ATC, however, only has four enforceable speeds, explained SEPTA’s train communications and signals chief Mike Monastero during a conference call with reporters this week. Train speeds along certain areas of track can only be regulated at 100 miles per hour, 45 miles per hour, 30 miles per hour and 10 miles per hour. Speeds in between aren’t enforceable. Additionally, speed limits can change within a single fixed block of rail, meaning it’s up to the engineer alone to maintain a safe speed under an ATC system along these stretches.

The Inquirer has reported that the northbound curve did not have that 100 miles per hour enforcement in place. “Generally, railroads only enforce the 45, 30 and 15 [miles per hour limits],” said Monastero. The southbound side, where trains are allowed to travel over 100 miles per hour shortly before the curve, has a 45 miles per hour regulator in place.

PTC systems also allow trains to communicate with one another and will automatically slow or stop a train if it’s rapidly approaching a stopped or slow train ahead.

The NTSB has called for PTC for more than 20 years and estimates that, not including last week’s tragedy, PTC could have prevented or mitigated more than 20 accidents, which resulted in 57 deaths and hundreds of injuries.

PTC is essentially ATC plus another system called Advanced Civil Speed Enforcement System. It’s the ACSES system that Amtrak has been working to install, and which provides the specific speed enforcement capabilities.

Amtrak has spent $111 million so far installing PTC. Amtrak had already installed PTC along other lines. According to the February edition of Amtrak’s employee magazine, ACSES is operational along the “New England Line from Boston to New Haven, Connecticut; the New York Line from New Brunswick to Trenton, New Jersey; and the Mid-Atlantic Line from Perryville, Maryland to Wilmington.”

NTSB officials said Amtrak 188 rapidly accelerated in little more than a minute from 70 to 106 miles per hour just before the crash. A PTC system would have sounded warnings once the train exceeded the limit and would have automatically stopped the train had the engineer not reacted.

Under the RSIA, only commuter rails and freight lines that share tracks with commuter lines are required to install PTC. Subways, trolleys and light rail are not required. The PATCO line uses an ATC system.

Amtrak was one of just three of the forty-one rail operators falling under the federal mandate that was on pace to meet its December 31, 2015 deadline. SEPTA and Southern California’s Metrolink are the other two — a deadly Metrolink crash in 2008 spurred Congress to pass RSIA. There, the engineer was texting as the train ran a red light and crashed into a freight train.

Tuesday’s derailment wasn’t the first fatal crash that could have been prevented by PTC since RSIA’s passage in 2008. A Metro-North derailment that killed four in New York City when a train was going 80 miles per hour in a 30 miles per hour zone in 2013 would have also been prevented by PTC.

Many commuter rail lines have said they cannot complete implementation on time, and have called on legislators to extend the deadline to 2020. U.S. Sen. Pat Toomey (R-Pennsylvania) has previously supported extending the deadline.

While PTC helps trains communicate with one another and the track’s signal system, miscommunications and other human errors only account for about 35 percent of train crashes, which are exceedingly rare to begin with. For example, PTC wouldn’t have prevented either of oil train derailments in Philadelphia over the past two years — both were caused by track defects. And PTC wouldn’t have stopped the commuter train in Valhalla, New York from colliding with an SUV stuck on the tracks.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.