Explainer: Cities, boroughs, and townships, oh my! Pa. municipalities clarified

There are thousands of municipalities in Pa., and it’s not always clear what the differences between them are. We explain.

Ever drive along a road where signs welcoming you to a borough or township appeared more frequently than stoplights? Pennsylvania is broken up into myriad units, many with overlapping jurisdictions, different powers and responsibilities, and varying classifications. For example, I live in the municipality of Allegheny County, which is a county of the second class, in the city of Pittsburgh, which is a second-class city. Sometimes I go to the movies in the borough of Homestead or visit friends who live in Shaler Township. Here’s a breakdown of what that actually means and what the differences are between the various entities.

What is a municipality?

Municipality is the catchall phrase for any county, city, borough, incorporated town or township. Basically, it’s a defined political subdivision unit in Pennsylvania, though it doesn’t include yet other units like school districts or authorities. Municipalities other than counties can also be called municipal corporations, and these are generally located within a county. But because Pennsylvania doesn’t like to make things easy, some municipal corporations, like Ellwood City — which, by the way is not a city, but a borough — actually spread across county lines.

All Pennsylvanians live within two types of municipalities — a county and a municipal corporation — and pay taxes to them. Municipalities like cities, boroughs and townships follow codified laws that define their governments and duties, but municipalities wanting more control can draft a charter and establish home rule.

What is a county?

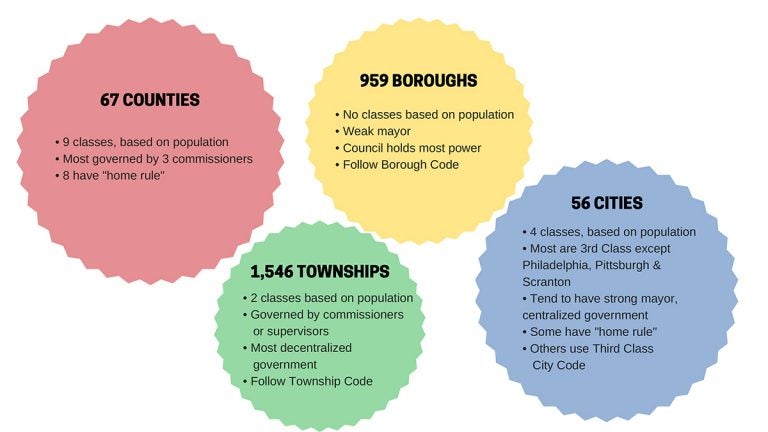

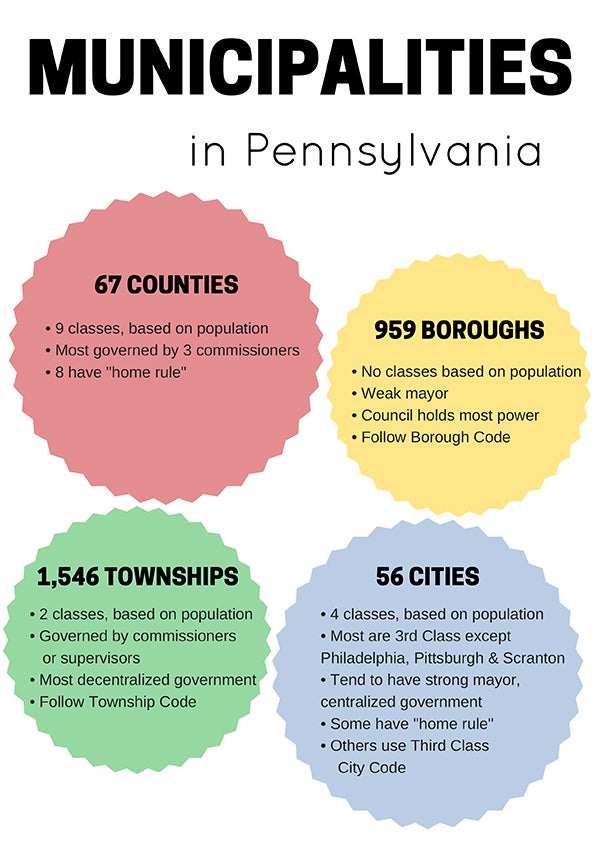

A county is one kind of municipality. There are 67 counties in Pennsylvania, broken into nine classes depending on their population. According to the County Commissioners Association of Pennsylvania, counties are required to provide certain services to their residents, including: judicial administration, corrections and justice-related activities, community development, environmental planning, public health and safety, human services, elections, and real estate tax assessments.

Most counties are governed by a three-member Board of County Commissioners. Eight counties have adopted home rule and have a different government structure.

What is a city?

Many of the cities in Pennsylvania were boroughs that sought recognition as cities as they grew bigger. Today, a borough with at least 10,000 people can ask to become a city by putting the question to its voters. (There’s little motivation for a borough to do that; laws that once made it easier for cities to drive redevelopment, for example, have since become pretty similar in boroughs.) There are 56 cities in Pennsylvania, which is fewer than there are counties (67) and just a small percentage of the total number of municipal corporations (2,562).

There are four classes of cities in Pennsylvania. First class cities have over one million residents and there’s only one such city: Philadelphia. Pittsburgh is the only second class city in the Commonwealth, and Scranton is the sole second class A city. Scranton used to be a second class city, as well, but wanted to separate itself from Pittsburgh. In 1921, an article in the Reading Eagle had then-Mayor Connell asserting “We can’t afford to attempt to operate Scranton like Pittsburgh. It is like running a Pierce-Arrow automobile alongside of a Ford.” No one compares Pittsburgh to very fancy cars these days but the second class A arrangement, created in 1927, stands.

The remaining 53 cities are all third class. Pennsylvania has what’s called a uniformity clause in its constitution, which bars legislators from levying taxes specific to just one city or municipality, or on one group of people and not another. The uniformity clause, however, recognizes certain classes, like the different class cities, so the designations help lawmakers skirt that rule by making laws for all first class cities, for example, even though in practice it would still apply only to Philadelphia.

Cities, especially of the first and second class, tend to have a strong mayor and, thus, a more centralized government. As governmental units, cities generally have broad powers, and all first class and second class cities – i.e. Pittsburgh, Philadelphia and Scranton – have home rule charters, which further expands their autonomy. Third class cities follow the Third Class City Code.

What is a borough?

Boroughs are defined, incorporated political subdivisions, but they tend to be smaller than cities. Most of the 959 boroughs in Pennsylvania, for example, have populations under 5,000, though there are exceptions. Boroughs follow a Borough Code; they tend to have a weak mayor system, where the elected council holds the majority of the power. The mayor is primarily responsible for oversight of law enforcement, but can break a tie in council, as well. The council can appoint a manager to institute policies.

What is a township?

Townships are, generally, even smaller than boroughs, though there’s a lot of variation with that, as well. Pennsylvania’s 1,546 townships are separated into two classifications; by default a township is a second class township, but if it has at least 300 people per square mile it can offer residents the chance to vote the township into first class status.

It’s the oldest form of government in the U.S., with decision-making power in the hands of supervisors, or commissioners. It is the most decentralized form of government. The two classes of township can have different numbers of elected commissioners, and first class townships can elect commissioners by wards rather than at large. They function under the Township Code.

What is a town?

There is just one incorporated town in Pennsylvania, Bloomsburg. It has six council members elected at large. The mayor is a voting member of council. In that way the mayor has more power than a borough mayor, but the at large election of council members is similar to townships.

For many Pennsylvanians, the distinctions in management and governance are less than obvious. As one Borough Council Handbook acknowledged, “It has become very difficult to draw a meaningful line between urban and rural municipalities, and between cities, boroughs and surrounding townships, especially when considering police protection, refuse collection and disposal, sewage facilities, economic development, housing, flood control and water supply.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.