Expect politics aplenty as School District of Philadelphia moves to close schools

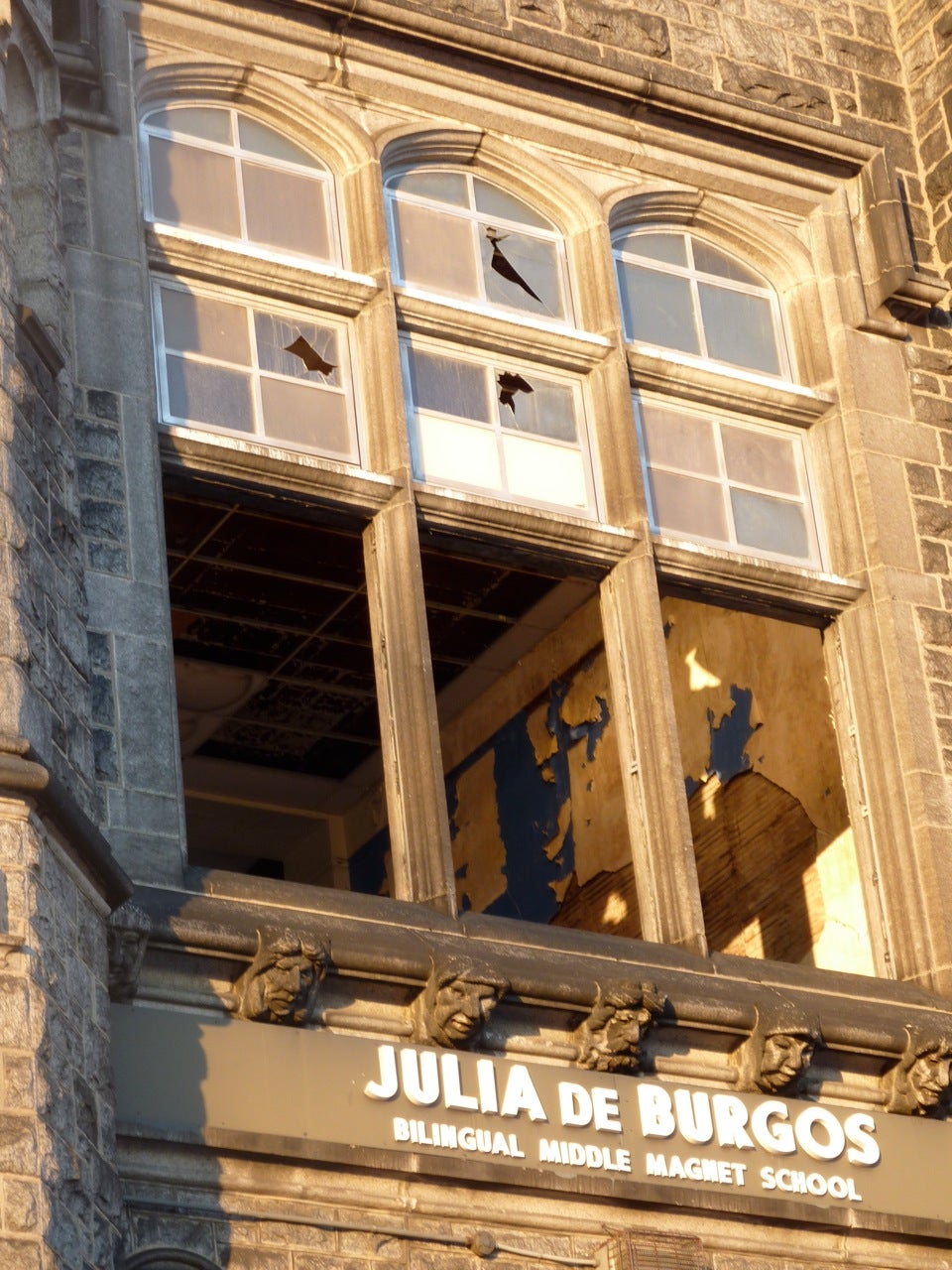

It is not yet entirely clear how the School District of Philadelphia will handle the biggest downsizing in its history. As many as 50 facilities are slated to be sold off in coming years, but the district has no plans to identify them until October, and the policy governing those sales remains a work in progress.

Will the process be transparent? Will neighborhoods have a real say? Will politically favored developers and non-profits have an inside track? It is simply too soon to say.

But school district policy is only part of the process. The laws and traditions of the City of Philadelphia shape virtually every major development project, and the rules of that game are well-established.

Most buyers of school properties – certainly those who plan to use a facility for a non-educational purpose – will be required by law to work their way through the city’s development bureaucracy, a process that is extraordinarily sensitive both to political pressure and community sentiment.

“I think we’d want to take a look at every site, and certainly some of the more prominent ones we will have particular concerns about,” said Gary Jastrzab, executive director of the Philadelphia City Planning Commission.

Which means that, even after the school district sells off its land, there is likely to be ample opportunity for those affected by facility closures to shape their redevelopment.

The City’s Role in the Sales

Officially, the city has no say in which schools will be closed.

But when it comes to selling the parcels – and deciding which new use is best for the land – the city could wield significant influence.

To begin with, the school district is using the property sale procedures of city agencies like the Redevelopment Authority as loose templates for their own adaptive re-use policy, school officials said.

More important, though, is the fact that a representative from the city Planning Commission will sit on the evaluation teams that will vet redevelopment proposals for each site. Though the city’s representative will be just one voice among many on the teams, the district is counting on the Planning Commission to provide context about other nearby developments, community groups that are active in the area and to identity possible uses for the sites, said Danielle Floyd, the district’s deputy director for strategic initiatives.

“We will be providing information about the areas where these properties are located, and we will offer advice and recommendations for how they might be re-used,” Jastrzab said. “We want good uses that are compatible with their surrounding neighborhoods, and we’re excited to have a voice in that.”

Depending on what school facilities are put up for sale, the city itself may be interested in purchasing some parcels, Jastrzab said. As part of the city’s comprehensive district planning process, which is beginning soon, the Planning Commission will be examining city facilities like rec centers and health clinics “with an eye toward the consolidation or joint use of facilities,” Jastrzab said.

It is possible some of the closed schools would make for good locations for consolidated city service centers, Jastrzab said, though he hastened to say he was only speculating. The city would be well-positioned to get parcels it might want, given that the evaluation teams will be looking to the Planning Commission for guidance on re-use options.

Politics As Usual

If precedent is any guide, the Planning Commission’s influence will be matched or topped by that of the 10 City Council members who represent different sections of the city.

Like the Planning Commission, district council members are granted only one representative per evaluation team by the district’s draft re-use policy.

But as a practical matter, district council members wield virtually bullet-proof veto power over any major development in the communities they represent, and school redevelopment projects are not likely to be an exception.

There is no legal basis under-girding this authority, which is known as councilmanic privilege or councilmanic prerogative. Rather it is a matter of tradition and deference: district council members anxious to protect their own power will, as a matter of course, unquestioningly follow the lead of a fellow district council members on votes concerning zoning and development in their fellows’ districts.

Formally, councilmanic privilege plays no role in the School District’s sale of facilities, as no council vote is required for the transactions. But it is worth asking: how many developers would submit a bid for a school district parcel without getting at least a tacit nod in advance from the district council member?

Thus far, council members are not tuned in to the school-closings issue. But that is sure to change once the 50-facility roster is announced.

“People are frightened, but they’re waiting to see who’s getting closed,” said Councilwoman Jannie Blackwell. “Once we know that, it’ll be a big deal believe me.”

The Development Gauntlet

Once the district sells off a property – be it to a private developer, a charter school operator, or a community non-profit – the new owners will, in most cases, still have an extensive series of hurdles to clear before they can redevelop the land.

With the exception of charter schools and other possible educational buyers, new owners of school lands will in many cases need special dispositions from the city to proceed with their plans, such as zoning variances or, possibly, property subdivision.

For instance, before converting a shuttered high school with residential zoning into a condo facility with ground-floor retail, a developer would need a zoning variance. That means submitting design plans to the Planning Commission, and going before the Zoning Board of Adjustment for the variance. Finally, a City Council vote is necessary for projects that require adjustments to city streets

It is, as a political matter, virtually impossible for developers to clear those hurdles without first winning over key neighborhood organizations and civic associations. Indeed, the ZBA requires developers to have met with such groups before it will consider a variance.

Looking Ahead

None of this is imminent. The School District so far is sticking to its plan to name the facilities it plans to close in October. It will take as long as three years to close the buildings and sell them off, the district has said.

This summer, though, the district will form evaluation teams to consider new uses for seven surplus properties that have already been decommissioned.

“We want to see how it works and based on that we may decide to revise the process, figure out a way to make it better if necessary,” Floyd said.

Contact the reporter at pkerkstra@planphilly.com

This story is a product of a reporting partnership on the district’s facilities master plan between PlanPhilly and the Public School Notebook.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.