Javonna Lee hasn’t been sleeping much.

For the last few months, she, her husband and their four kids have been staying in the living room of her sister’s place: 10 people crammed into a dimly-lit three-bedroom apartment in Reading, Pennsylvania.

At night, Javonna, 33, and her husband share an air mattress with their two toddlers, while their two teenagers curl up on small, worn-out couches. On a good night, the adults get a couple of hours of sleep before the two-year-old wakes up, or someone steps over their air mattress coming home late after a night out.

“We are like smack dab in the middle of the living room, so there is absolutely no privacy whatsoever,” Lee said. “We are always waking up.”

Their lives were turned upside down by a simple mistake. Javonna’s husband supports the family on about $13 dollars an hour. Last summer he was making a little extra money working on a moving crew in a rented truck and he lost his wallet containing a prepaid debit card loaded with his paycheck. With no bank account and no savings, Javonna and her husband quickly fell behind on rent.

They were in eviction court in July. Their landlord said the couple was chronically behind on rent. By August, they were out of their home.

Javonna, her husband and kids stayed in a storage unit for a week after they were evicted, then spent some time in emergency housing before bouncing to her sister’s apartment.

The eviction didn’t just take the family’s home, it took their community, too. Javonna’s sister has been violating the terms of her lease by hosting them, so they try to be seen and heard as little as possible. At their last apartment, Javonna helped organize a block party; now she can’t even sit on the front stoop.

Reading, where Javonna grew up and has lived almost her whole life, now feels unfamiliar and cold. She wants to move.

“[I want to move to] Pottstown, Spring City, Philadelphia, I could go on,” she said, trailing off with a giggle that seemed close to tears. “Anywhere. I want to leave here.”

***

Javonna’s story is not rare in Reading.

The working-class, Berks County seat has the highest eviction rate among Pennsylvania’s five largest cities, according to a national database published by Princeton sociologist Matthew Desmond. It’s a major problem in a city where renters occupy most of the housing units. In 2016, about three households were evicted every day, and more than a tenth of all renter households received an eviction filing.

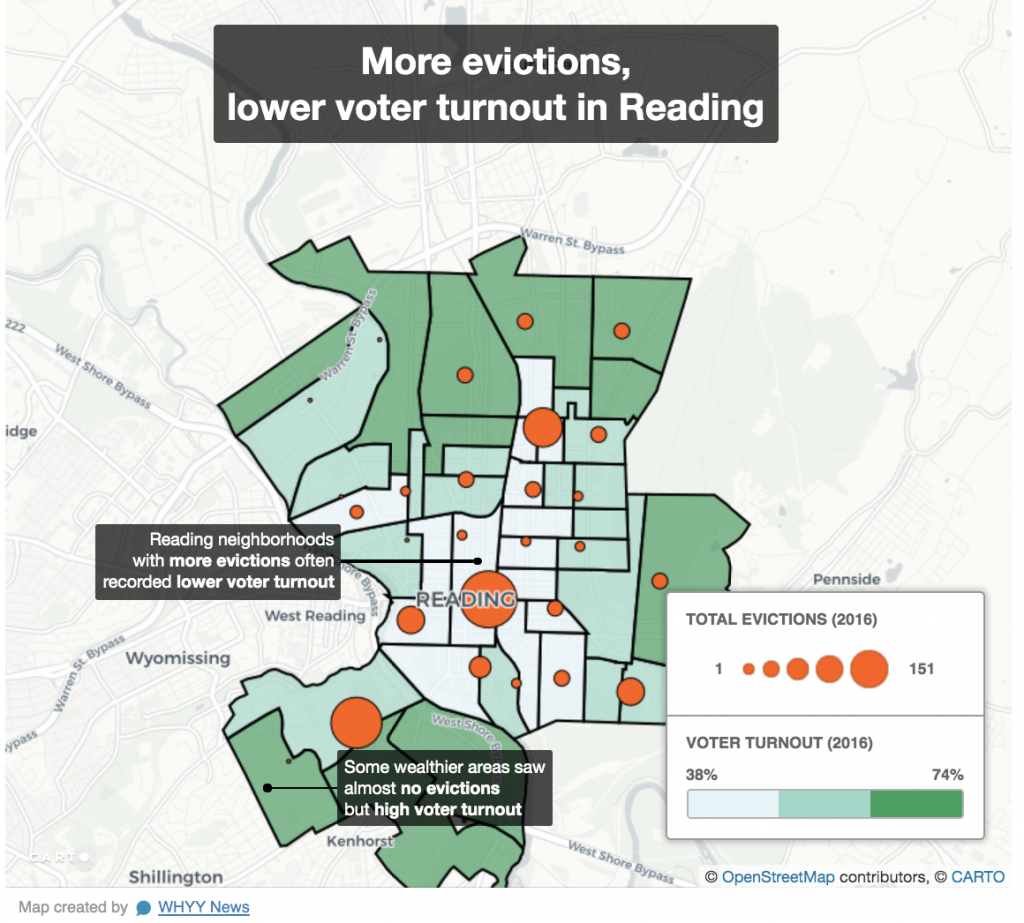

A Keystone Crossroads’ analysis of 2016 data shows that neighborhoods in Reading with more evictions often had lower rates of voter turnout in that presidential election year.

The housing instability extends beyond eviction. About a third of all renters in Reading moved within the last year, significantly higher than the statewide figures.

These dynamics may affect Reading’s role in the upcoming presidential election. Although Reading is Pennsylvania’s fifth largest city, its voting rate lags behind comparatively. The heavily Democratic city has seen a lower percentage of voting-eligible residents go to the polls than peer cities in most non-primary elections since 2014, according to a Keystone Crossroads’ comparison of voting data and census estimates.

Experts say evictions likely factor into those low numbers.

“All else being equal, if you live in a neighborhood with high eviction rates, the voting rate is significantly depressed,” said Desmond, America’s foremost eviction scholar, who has a forthcoming paper on the issue.

The heavily Democratic city will likely be a tempting target for the candidate running to defeat President Donald Trump.

Registered Democrats outnumber Republicans by more than five to one in Reading, and motivating voters in Berks County could be critical to winning Pennsylvania in the 2020 election. In 2016, President Trump won Pennsylvania’s 20 crucial electoral college votes by edging Hillary Clinton by just 44,000 ballots.

The roughly 29,000 thousand Reading residents who were eligible but did not vote in 2016 could be called other swing voters — a term for the primarily young people of color who, instead of swinging between Democrats and Republicans, alternate between voting Democrat and not voting at all.

Javonna has voted before. In 2008, Barack Obama’s first presidential election campaign brought her to the polls. She says she also voted for him in his second run. But, in 2016, Javonna sat the race out, uninspired by the candidates.

“If I was going to vote for [Clinton] it was more because of her husband. And that’s not fair, so I just didn’t vote,” Javonna said.

She considered voting in last year’s mayoral election, but “there was too much going on.”

“If you have a living situation and everything is stable, your mind has more things to focus on other than trying to find a home,” Javonna said. “[So] of course you can be more active in the community.”

***

Javonna was surprised by how quickly her landlord-tenant case unfolded in a Reading courtroom last July. The judge took just fifteen minutes or so, Javonna said, to rule in favor of the landlord. The whole process felt strangely informal, a feeling accentuated by the drab municipal setting.

“It looked like a little lunchroom. Little tables with little pull out chairs. it was nothing fancy,” she said.

Fifteen minutes is on the long end for many eviction hearings in Reading. During one recent afternoon in Magisterial District Judge Tonya Butler’s courtroom, tenants in half of the eight cases called didn’t show up. Those cases took less than a minute, with Judge Butler ruling against the tenants every time.

Metal chairs take the place of traditional wooden benches in Butler’s courtroom, and bright fluorescent lights blare from a dropped ceiling. Bibles are glued to the plaintiff’s and defendant’s tables facing the judge.

Reading is now about two-thirds Latinx, up from a third at the turn of the century, and most of the tenants who came to court that day were Latinx as well.

Sonia Arias, who doesn’t speak English, was confused why she had to be in court at all. Through an interpreter, she told Butler and her property manager that she had been paying cash to a man named “Francisco” who came to collect every month. After several befuddled minutes, Arias and the property manager figured out that Francisco was a former tenant who masqueraded as the owner to rip her off. Judge Butler was sympathetic, but ruled that the landlord was entitled to three months of back-rent.

Every time Butler ruled against a tenant — the outcome in most of the cases that day— she made a point of distributing information on social services that offer cash assistance for people facing eviction. But, each time, she added the caveat that, as far as she knew, those agencies were out of funding for the year.

“It is difficult,” Butler said. “But I have to work within the parameters that the law has provided to me.”

Kimberly Talbot knows better than most how much many of Reading’s tenants are struggling. Talbot is the executive director of Reading’s Human Relations Commission, an agency that enforces fair housing rules, and provides cash assistance and other forms of aid to renters.

The agency has seen a 45% increase in clients since 2015.

“When I first came here I thought the rents were reasonable,” said Talbot, who has been with the agency since 2007. “As time has progressed, rents have seemed to soar. People are struggling every day.”

The biggest reason for that struggle is simply that Reading is poor. It’s poverty rate is about 35%, and unemployment is at 7.3% — both well above the state average. But local stakeholders say housing issues are especially acute for recent arrivals from the New York City metro area, who often speak little or no English.

“There are a lot of people who…sign leases, actual legal documents, and don’t understand a word of it,” Talbot said.

Evictions feed another growing housing issue in Reading: illegal rooming houses. Multiple sources described off-the-books housing where tenants pay as little as $50-a-month to rent beds, or just a spot on the floor.

Cinthya Delarosa, 33, who moved to Reading from the Bronx, lived in one such house with her four kids briefly last fall. The building was falling apart –– bedbug infested, with a mold problem so severe that mushrooms had sprouted on the ceiling –– but when Delarosa sought to withhold rent in exchange for repairs, the landlord told her to get out.

She received the eviction notice on November 4th, just before Election Day.

“That voting day I couldn’t think about nothing but…where we were going to stay.” Delarosa said.

Many of the Democrats vying for their party’s nomination for the presidency have housing plans that specifically address evictions. Amy Klobachar, for example, is calling for a new kind of savings account renters could tap in a housing emergency. Bernie Sanders wants to limit the conditions in which landlords can file for eviction.

The fact that the issue is even factoring into the presidential debate testifies to its growing national impact. Reading is one of many American communities experiencing higher rates of eviction than in the past, a growing crisis tied to shortages of affordable housing across the county.

Still, housing has made the debate stage far less than many other issues, reflecting the idea that politics is rarely a priority for people struggling to keep a roof over their heads.

“A lot of our clients in all honesty are trying to get from day to day, from minute to minute. Sometimes that’s all they have,” said Kim Talbot. “They can’t afford to look at someone’s housing strategy, because it’s not going to affect them today.”

In Reading, eviction has spurred little political action. Eddie Moran, the city’s new Democratic mayor, has promised a “comprehensive” housing plan to improve Reading’s housing stock, but his administration has yet to release it, and did not respond to several requests for comment.

***

Eviction can be especially hard on Latinx people who moved to Reading from elsewhere — those who lack a built-in community to fall back on.

Jen grew up in a low-income, largely Puerto Rican neighborhood in the Bronx, living in cramped housing and constantly worried about violence. She knew little about Reading except that houses were cheaper and her then-boyfriend’s brother lived there. That was enough. In 2011, she dropped out of high school, packed up, and moved 150 miles southwest, along with her boyfriend.

“Our goal was, like, buying a house, getting a job, building a family,” she said. “So we decided Reading.”

In 2018, Jen got involved with a man who physically abused her. Her new boyfriend wouldn’t watch Jen’s two young sons, and she struggled to support them all by working part-time data entry and warehouse jobs. (Keystone Crossroads is not using her real name for her protection.)

Within a few months of moving in together, she fell behind on rent. Jen’s landlord called. Her choice was to leave, or face eviction court.

“I felt….hopeless. Like OK, where are we going? We don’t have family here, we don’t have anyone here,” said Jen, now 25. “How are we going to do this?”

Over the year and a half that happened three more times.

Amber Wichowsky, associate professor of political science at Marquette University, said people subject to that kind of eviction-driven transience are less likely to be correctly registered to vote, or have their door knocked by political canvassers. And they lose out on a sense of community-identity that often sends people to the ballot box.

Jen, for instance, has never voted.

“If you are a frequent mover and don’t have time to build deep roots in your community, get to know your neighbors, you may be less likely to be exposed to the kinds of social conversation, social pressure that can also make us more likely to be engaged in political life,” Wichowsky said.

By early summer last year, things had finally started to turn around for Jen. First, her abuser went to prison on an unrelated gun charge. Then she obtained a rent-subsidized apartment through a local non-profit: a lucky break in a city where thousands of people apply for a spot on the waitlist every year.

Lately, Jen has been settling into something close to a routine. She got hired as a healthcare aid at a nursing home, and is working to obtain her G.E.D.

And she’s started to pay a little bit more attention to politics too.

“I definitely like Bernie Sanders,” she said. “I’ve been seeing him do things for homeless people…with hunger, you know.”

For Sanders, getting people like Jen out to the polls could be essential. The Democratic Socialist is banking on turning out occasional and non-voters, especially those who are Latinx.

Still, Jen is not yet committed to the political process, or the city of Reading. She doesn’t know her neighbors, has not registered to vote, and drives back to the Bronx to visit family every chance she gets.

Asked whether she plans to vote in Pennsylvania’s Democratic primary in April, or in November’s general election, she said, “hopefully.”

***

In early February, Javonna and her family received their first bit of good news in months: a Reading landlord had accepted their application to rent a house.

Finally having a place of their own is exciting, but it will mean more instability for Javonna’s thirteen-year-old daughter, Jayonna. She had to transfer middle schools when the family was evicted, and will have to transfer again when they move.

“I’m usually by myself, you know,” Jayonna said. “So my friend group is a little tiny.”

Turnover at Reading’s public schools is such a major problem that, in 2015, the district switched to a single sports mascot for all of Reading’s 20 traditional public schools.

“If you have a kid that may be at four elementary schools in one school year, they aren’t sure if they are a Tornado or a Viking,” said Superintendent Khalid Mumin. “They’re not sure.”

Now, every student in the district knows at least one thing for sure: They are a Red Knight.

For Javonna and her family, stability may be on the horizon, but they still have a ways to go. The previous tenants at what will soon be their new house kept livestock inside, and it’s been uninhabitable. The landlord offered six weeks of free rent if the family cleans it themselves. So, once they pick up the keys, they’ll spend days scrubbing before moving in.

Once they settle, Javonna said she’s looking forward to having more time and energy to focus on the big picture. She’s hoping, for instance, to learn more about Bernie Sanders. But she isn’t ready to commit to voting for him, or anyone, until life on an air mattress in her sister’s living room is a distant memory.

“If I had a home we could do all that extra stuff, like voting and parent teacher conference,” she said. “But, when you are in a situation like this, your mind is so overwhelmed with trying to get stable you can’t think of anything other than trying to put yourself in a home.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.