‘The voice of the people will be heard’ — from Vietnam protests to the new resistance

Like Americans who demonstrated against the Vietnam War in the late '60s, today's protesters know that it takes more than just one disruption to get the country and its electe

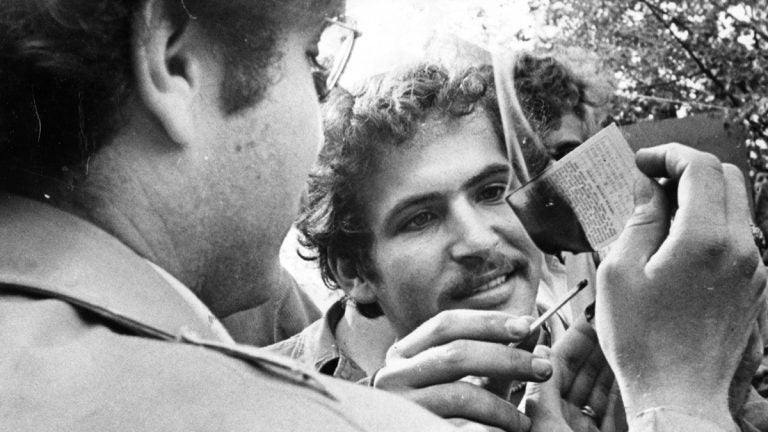

Two men are shown burning draft cards at a Jan 31, 1977, rally at J.F.K. Plaza. (Joseph Wasko / Courtesy of George D. McDowell Philadelphia Evening Bulletin Collection, Temple University Libraries)

This story is part of a WHYY series examining how the United States, four decades later, is still processing the Vietnam War. To learn more about the topic, watch Ken Burns and Lynn Novicks’ 10-part documentary “The Vietnam War” running Sunday, Sept. 17 at 8 p.m. through Thursday, Sept. 28 on WHYY-TV.

—

Last year, I was flying home to Philadelphia from Minnesota, days after Philando Castile was murdered during a traffic stop with police. As a friend and I caught a quick drink at one of the airport bars, our conversation with the bartender quickly turned to the protests that were happening across the state.

“I hate it when they stand in the middle of the street and keep people from getting to where they are going,” he told us. “Those protesters kept an ambulance from getting through. They kept a dying man from getting help.”

My friend put down his drink. “Philando Castile was a dying man, too,” he replied in a kind albeit direct voice. “Where was his ambulance?”

I can’t say for sure if a dying man’s ambulance was held up by this protest, but I imagine that my friend’s question is shared by the hundreds of thousands of Americans who have marched for Philando Castile and others who have died during interactions with police since last July. Like Americans who demonstrated against the Vietnam War in the late ’60s, today’s protesters know that it takes more than just one disruption to get the country and its elected officials to pay attention.

Dissenting ripples that become waves

I see many similarities between the protests happening now and the demonstrations 50 years ago against the Vietnam War. Then, as now, the country was ideologically split down the middle. A conniving leader hell-bent on destroying political opponents, dissenting voices, and the media became president. Stories of police brutality against unarmed African-American citizens came daily. Technology played a key role in communicating the horrors of war overseas and violence at home.

Protests are as essential to American history as the wars we’ve waged in the name of defending freedom, because the act of protesting provides another way to carry out democracy when our existing systems of government fail us. The protests fueled by resentment of the Vietnam War showed elected officials and the rest of the country, in a very public, organized series of demonstrations, that we could not be “defenders of democracy” abroad if we couldn’t uphold democracy here at home.

The anti-war movement started out small, and as with the marches and demonstrations happening now, key figures and technology propelled the movement forward. After the Gulf of Tonkin incident saw the deployment of more American troops in 1964, the seeds of the defiance were sown in college campuses across the country. As American involvement in the war increased, so did the number of key dissenting voices.

Muhammad Ali was among them. The parallels between Muhammad Ali’s stance against the war in Vietnam and former San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick’s kneeling protests during the national anthem before games last year are most striking. Ali refused to be drafted into the U.S. military, which would have deployed him to Vietnam. The decision cost him as an athlete (he was unable to obtain a boxing license for three years, and his title and commissions were stripped away) and as a citizen (he was arrested and convicted for defying the draft).

Kaepernick’s refusal to stand during the national anthem, to protest the murders of unarmed black men by police officers, earned him the respect of fans and activists across the country, but led to him becoming blacklisted by the NFL and the target of death threats. Their demonstrations may have cost them personally and professionally, but Ali and Kaepernick helped shine a spotlight on the injustices they rallied against.

Television also played a significant part in turning the tide of public support, because satellite technology made it possible to broadcast the horrors of war live during the evening news. Communications from the White House weren’t lining up with the true stories on TV. And the country was seeing the enemy from a different perspective: news stories of children with their clothes burned away by Napalm and small villages being massacred by American soldiers demonstrated that something was terribly wrong with our quest to stop the spread of Communism.

When Walter Cronkite declared on television on Feb. 27, 1968, that the war could not be won, the dissent went mainstream. Demonstrations with hundreds of thousands of people took place in Washington, D.C. and young men began burning their draft cards in protest.

Social media is the messenger of the movement now. Americans never would have seen Philando Castile’s death without Facebook Live. We never would have known that police officers were pepper-spraying peaceful protesters at the University of California-Davis in 2016 without YouTube videos shot by people who were there. We never would have seen a nurse dragged into a police car for doing her job in Utah if we didn’t have access to the technology that made livestreaming possible. These instances may not seem related, but they show a side of law enforcement that we as Americans have accepted without question until now, because we’ve never seen them from the perspective of the person being taken into custody.

‘Why we march’ — then and now

By the time American troops departed Vietnam in 1973, the nation was caught in a relentless whirlwind of accomplishments and setbacks. At one point, an Equal Rights Amendment guaranteeing equal legal protections for women and Richard Nixon’s visions for universal healthcare and daycare were within reach, but then the tide turned against the Women’s Movement when straight, white middle class women could not embrace gay rights as part of their agenda, and Nixon’s paranoia and ongoing harassment of his political adversaries brought him down during the Watergate investigation.

When you compare the two eras, the anti-war movement and the resistance movements against abuses of police authority, systemic racism, and even the Donald Trump presidency, the importance of protest becomes clear. Then and now, we are divided by political ideologies, but we all have the same desire — to have access to healthcare, education, and information without limitations, real or perceived. What many of us have failed to grasp in both instances is that protecting life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness takes ongoing dedication and vigilance.

To paraphrase a speaker at the “Philly is Charlottesville” rally last month, in order to break the silence, we have to show up. We have to fight for what is important in our daily lives, long after the demonstrations have ended. Tired of seeing the same people (old white men) in office at the national and local level? Vote them out in favor of a more diverse pool of candidates who know how to organize and enact change.

Tired of reading stories about gun violence? Beat the NRA at its own game and lobby every day, before deadly incidents happen, for laws that keep citizens safe.

Tired of seeing women harassed on the street or undervalued in the workplace? Be an outspoken ally and demand a world that is safe and empowering for everyone.

Protest is the first and last tool for the common man, when democracy fails and the public chooses to turn a blind eye to inequality and the suffering of the most vulnerable in our society. But protest can take many forms, and it takes many acts of nonviolent disruption for the nation to pay attention and take action.

—

To learn more, watch Ken Burns and Lynn Novicks’ 10-part documentary “The Vietnam War” running Sunday, Sept. 17 at 8 p.m. through Thursday, Sept. 28 on WHYY-TV. WHYY Members will have extended on-demand access to the series via WHYY Passport through the end of 2017.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.