Del. police have shot 56 people since 2005, but law ‘immunizes’ them from prosecution

Despite making up 22% of the population, Black people make up nearly half of those shot by Del. police. Now, the state’s AG wants to change the use-of-force law.

Over the last 15 years, police in Delaware have shot 56 people, three this year alone.

Officers have killed 30 of them, including an innocent robbery victim.

Nearly half of those shot were Black in a state where Black people make up just 22% of the population, according to a WHYY News analysis. That finding reinforces concerns by many First State residents that systemic racism in police forces puts a target on Black suspects.

While circumstances have varied, every Delaware police shooting has one common denominator: No officers have been charged with a crime — even in instances where their use of deadly force has been questioned by state prosecutors, members of the public and lawyers for the people shot.

WHYY News analyzed Delaware police shootings since 2005, but several veteran attorneys and law enforcement officials said they cannot recall a case even before that year where a Delaware cop was arrested for shooting someone.

That fact has led advocates for Delaware police to assert over the years that each shooting has been a “good shoot.”

That glib declaration, however, doesn’t take into account what then-Attorney General Matt Denn’s office cited in 2016 as the key factor shielding Delaware police officers from arrest: the state’s 70-year-old law governing the use of deadly force.

The law allows officers to pull the trigger if they “believe such force is necessary’’ to protect themselves or others from death or serious injury.

The Denn report concluded the law “provides a great deal of deference’’ to police because it lets their “subjective belief’’ of imminent danger govern their decision to fire their guns — a provision that “immunizes them from criminal responsibility.”

But in the wake of recent protests against police brutality across Delaware and the nation, Denn’s successor has proposed changing the law to make it easier to charge an officer with illegally using deadly force.

The conclusion reached by Denn’s office four years ago was part of the state’s investigative report into whether Wilmington police broke the law in September 2015 when they fatally shot 28-year-old Jeremy McDole.

McDole, who was Black and used a wheelchair because he had been paralyzed from the waist down, was gunned down by four officers — three white and one Latinx — who responded to reports McDole had shot himself in the middle of the street.

Prosecutors wanted to file felony assault charges against the white officer who rushed to the scene and fired on McDole within two seconds of telling him to show his hands, but decided they could not. The scathing 31-page report by Denn’s office blamed the state’s use-of-force law, emphasizing two words in bold type:

“A police officer need not establish that the use of deadly force was actually necessary to protect the officer against death or serious physical injury,’’ the report said. “All he must show is that he believed that to be the case at the time that he used deadly force, whether his belief was reasonable or unreasonable.”

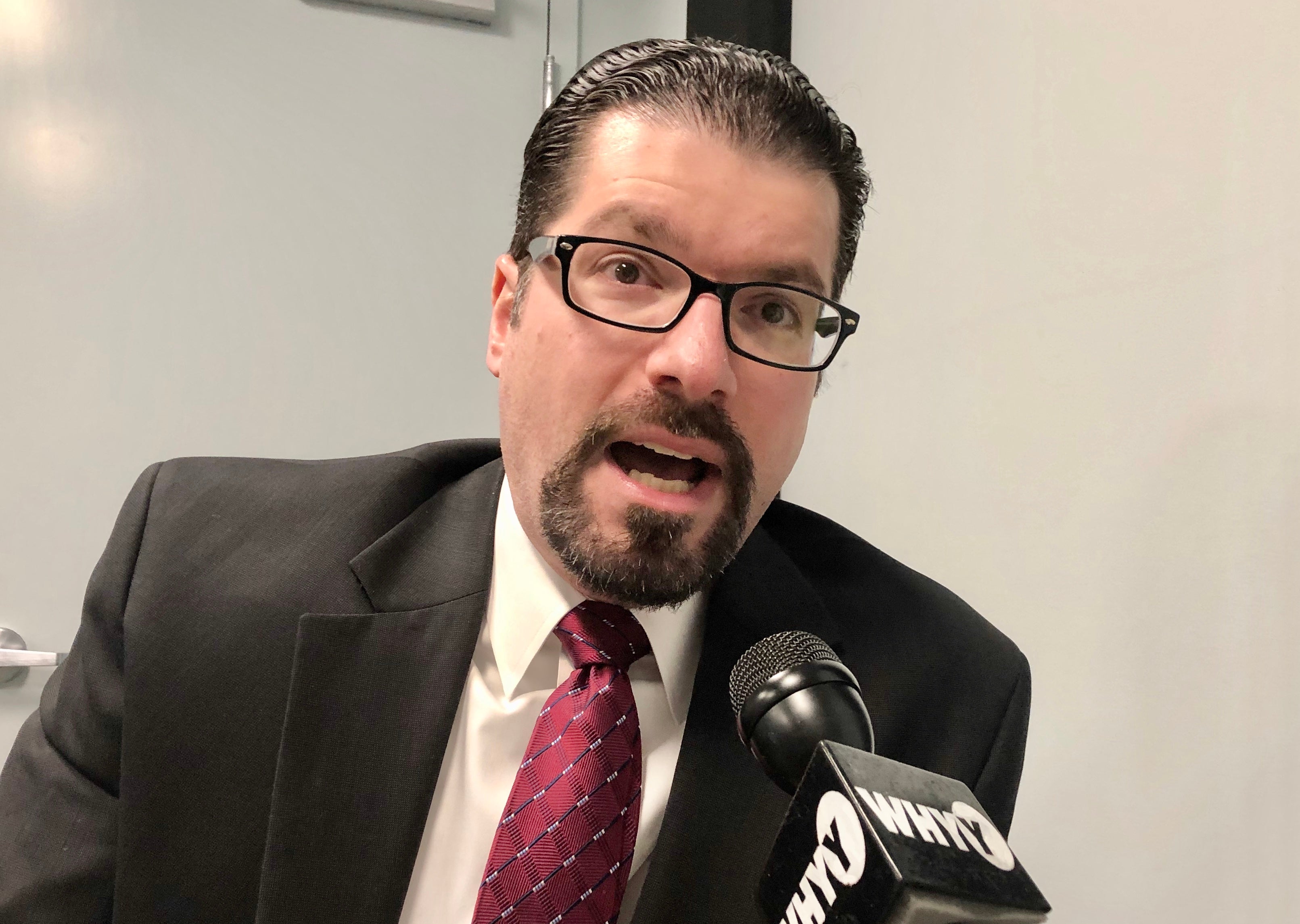

Attorney Stephen Neuberger, part of the legal team that settled a federal lawsuit on behalf of McDole’s family against Wilmington for $1.5 million and has represented families of other men killed by police, calls the Denn report an “extraordinary’’ document.

“You basically need the police officer to say that ‘I had an awareness, I knew what I was doing was wrong,’’’ Neuberger told WHYY News.

Law must change, AG says after nationwide unrest

Even though the Attorney General’s Office routinely lobbies lawmakers for legislative changes to the state’s criminal code, Denn never tried to change the law before leaving office in January 2019.

Denn, who is now in private practice, declined several interview requests since January, when WHYY News began examining police shootings after the killing of 27-year-old Brandon Roberts.

Denn’s successor, Kathy Jennings, would not speak with WHYY News at that time either, but a spokesman said she had made no efforts to change the statute.

However, on June 10 — after protests triggered by the killing of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer — Jennings announced that changing the law is high on her list of police reforms needed immediately.

“We have to do the tough stuff,” she said at a rally in Dover, convened by Delaware’s Legislative Black Caucus. “We have to change the things that haven’t been changed in this state for decades. Let’s bring it on and let’s get it done.”

At the rally, lawmakers announced a Justice for All package of bills.

Among the proposals: requiring body cameras for police forces statewide, banning knee and chokeholds, and making disciplinary findings against officers available to defendants. (Under Delaware’s Law Enforcement Bill of Rights, officer disciplinary records and proceedings are “confidential and shall not be released to the public.” Agencies responded to queries by WHYY News about whether officers were disciplined for specific shootings by citing that law.)

Jennings later told WHYY News that even though she had not previously gone public with her desire to amend the deadly force law, she has discussed doing so “for years and years.”

Jennings, a prosecutor or defense attorney for more than four decades, said she wants to change the subjective standard to an objective one.

To accomplish that, her legislative proposal, which she shared with a reporter, would require officers to “reasonably” believe deadly force is necessary, instead of simply believing it is necessary.

DOJ- Use of Force Bill 6.18.20 by WHYY News on Scribd

The bill’s synopsis says the proposed change “makes it clear that the determination of one’s state of mind is an objective standard — that is, what a reasonable person would have believed, rather than what the defendant believed.”

Jennings said the “horrific murder of George Floyd has galvanized our mission behind reforms that are needed. This is an opportunity that is upon us.”

WHYY News reached out to leaders of the state, New Castle and Wilmington police, the three largest forces in Delaware — before and after the Justice for George Floyd protests — but none would agree to an interview.

Wilmington police union president Gregory Ciotti, who recently retired after 34 years, said the last thing officers want to do is shoot suspects. They know they will be relieved of their guns, put on administrative leave and undergo internal and external investigations, Ciotti said.

“It takes a huge emotional toll on the officers,’’ Ciotti said, defending the current law. “It’s the worst possible situation.”

Milford man killed in January after calling 911

WHYY News began its analysis in early January, after two officers in Milford, south of Dover, killed 27-year-old Brandon Roberts.

Roberts was Black. Two unidentified officers — one white, the other Black — fired their weapons, said Thomas Neuberger, the father and law partner of Stephen Neuberger. The Neuberger Firm until recently represented Roberts’ fiancée Erica Jones, their young son Nasir and other relatives.

Roberts’ shooting is one of five by Delaware police officers since August 2019 that are still under review by Jennings’ office.

Roberts was killed after police responded to a “report of a domestic incident involving weapons,” police said.

Roberts emerged from the apartment into the hallway and was shot after “advancing at police officers while brandishing a large knife,’’ police said.

Police Use of Deadly Force Investigations

Police Use of Deadly Force Investigations

See the Delaware DOJ report on each shooting, including evidence, interviews, and legal analysis of police actions.

Authorities haven’t revealed more details, but Stephen Neuberger says that account is incomplete, if not inaccurate.

Neuberger said Roberts, who suffered from bipolar disorder and other mental health issues, called 911 himself and said he had a gun. His fiancée got on the phone and told police he was having a breakdown and was not armed, adding their 1-year-old child was home.

Roberts was off his medication, but not a threat, Neuberger said. “He’s just calling because he needs help.”

Police “began banging on the door,’’ the attorney said. “In the words of a couple of neighbors, it sounded like a drug bust going down. What happened next is what we’re investigating now.”

Jones said Roberts “never raised the kitchen knife from his side,’’ Neuberger said.

Milford police were wearing body cameras that night, but Jennings has resisted the lawyer’s calls to make the video footage public.

“This is going to be one of those situations where modern technology might be able to help us have more accountability in government, more transparency in government,’’ Neuberger said.

Among Delaware’s three biggest forces, New Castle County police use body cameras, but state and Wilmington police do not.

Mayor Mike Purzycki said this month, days after protests and widespread looting downtown, that the city will buy police body-worn cameras.

30 killed, 26 wounded since 2005

Delaware police officers have killed 30 people and wounded 26 since 2005. In one case, the intended target was not struck. All were males, three of them minors.

Overall, 26 of the people fired at were Black, 25 were white, three were Hispanic/Latinx and three were of unknown race or ethnicity, WHYY News found. Of those whose race is known, 48% were Black in a state whose population is 22% Black.

Of the 30 people killed, 14 were white, 13 were Black and police would not provide the race or ethnicity of the other three men, citing department policy.

Delaware police agencies also don’t release the race of officers who have shot suspects and the Attorney General’s Office reports also don’t include their race or ethnicity. In some cases, however, WHYY News has been able to learn the race or ethnicity of officers from news accounts, department reports on promotions and other matters, or through social media posts.

State Rep. Sean Lynn, a Dover Democrat and lawyer who chairs the House Judiciary Committee, told WHYY News this month he wants to require police to release the race of officers who use deadly force, among other reforms.

“How else would you be able to assemble statistical data?’’ Lynn said.

Reports ‘fully support’ officer in many cases

In the vast majority of Delaware police shootings, the Attorney General’s Office concluded deadly force was justified, given the suspect’s actions — even in a 2010 case in which an innocent robbery victim was shot.

State investigators said Eric Howell, who is Black, was threatening and pointing a gun at two kneeling men, then fired a bullet into the ground. Police told him to drop the weapon, but Howell pointed it at the officers. Det. John Ciritella, who is white, fired twice, grazing Howell in the head, but killing 38-year-old robbery victim Darrell Swain, who was Black.

The state’s report said authorities “fully support” the use of deadly force because the officer believed he was in immediate danger, as were the civilians being held up.

The report stressed that even though Swain was killed, the officer fired to protect himself and the robbery victims from “serious injury or death.”

Ciotti, the city’s police union president, said he does not recall Ciritella receiving internal discipline. Ciritella retired two years later after 28 years on the force and was hired as an investigator with the Attorney General’s Office, where he still works.

‘I felt I was in danger … and started shooting’

Several police shootings have troubled prosecutors — especially the 2015 police killing of Jeremy McDole in Wilmington.

McDole, known as “Bam Bam’’ to his family and friends, had been paralyzed from the waist down years earlier after being shot in the back by a man he had considered a friend, said his sister Keandra McDole. He lived in a Wilmington nursing home, but spent much of his time with family.

McDole was the oldest of six children, his sister said. She described him as outgoing and helpful, and said he was devoted to a young nephew.

She said her brother dropped out of school “at an early age,” and was “living the street life,” using and selling marijuana.

“He wasn’t a good kid,” Keandra McDole said, but “he wasn’t bad-bad where you should be terrified of him.”

On the day McDole was killed, his godfather later told authorities he wheeled McDole to the Browntown neighborhood to get a gun and buy PCP-laced cigarettes, the state’s report said. The man said he did not see McDole buy a gun, but was not with him the whole time, and they parted ways before the fatal encounter that occurred near businesses and homes in the Hilltop neighborhood.

The incident began about 3 p.m. after a 911 caller told dispatchers she heard three shots, saw a wheelchair tip over and the man in it fall to the ground. The woman told police the man had shot himself and urged officers to hurry because “he’s still got a gun,’’ according to the 911 tape.

Sr. Cpl. Daniel Silva, the first officer on the scene, told investigators the next day that he saw McDole climbing back into his wheelchair and repeatedly ordered McDole to show his hands. Instead, McDole reached into a bag and moved his wheelchair. Silva, who is Latinx, and his unidentified partner took cover behind parked cars.

Silva, who had not seen a gun, reported on the police radio that he was “not approaching” McDole because he didn’t know the full situation.

Other officers arrived, including Sr. Cpl. Joseph Dellose, who was not dispatched, but responded anyway. Dellose, who is white, parked his car, grabbed his gun and approached McDole.

Silva later said he yelled at Dellose “to retreat from where he was,’’ but Dellose said he didn’t hear Silva or any radio dispatches.

Instead, Dellose said, “I put my shotgun on target, told the suspect to show me his hands. ‘Show me your hands,’ I believe that’s what I was saying. I was screaming as loud as I could.”

Dellose said McDole didn’t respond and his hands were “fidgeting, you know, by his waist.” Dellose said he “could see the handle of a weapon.”

Dellose fired one shot.

“I felt I was in danger, my life was in danger if he picked up that gun and started shooting,’’ Dellose later said. “He could shoot the other officers, he could shoot me and bystanders.”

‘Only two seconds to respond’

Dellose fired his gun less than two seconds after ordering McDole to show his hands, according to the report and a video of the shooting captured by a bystander.

After Dellose pulled the trigger, officers kept ordering a visibly bloody McDole to show his hands, but instead, he was “alternately repositioning himself in his wheelchair and moving his hands on the armrests of his wheelchair’’ and then “reaching into his pants,’’ the report said.

Silva and two other officers, Cpls. James MacColl and Thomas Lynch, who are white, fired a fusillade of bullets, toppling the wheelchair and McDole into the street. His body remained there for hours, covered in a white blanket.

Officers said they found a gun under McDole’s body, but his mother and others have asserted he was unarmed. They held several protests, with some people accusing police of planting the gun.

Denn’s office concluded McDole had a gun and said gunshot residue was found on McDole’s hand, consistent with him firing a gun that day.

The state said Dellose’s actions were potentially criminal, however.

“After seeing other officers on the scene and eventually noting that they were yelling things he could not hear, [his decision] to nevertheless advance immediately up the middle of the street without seeking cover or assessing the situation could constitute reckless conduct as that term is defined in the Delaware criminal code,’’ the report concluded.

“His decision to discharge his firearm at Mr. McDole after giving Mr. McDole only two seconds to respond to verbal instructions could also constitute reckless conduct.”

Yet, after consulting with three police experts, Denn’s office decided it could not convince a jury “beyond a reasonable doubt.”

They tried to find an expert who could successfully counter anticipated testimony from a defense expert that Dellose’s actions were lawful. The experts they consulted said they could not do so.

That meant Dellose would be able to present “unrebutted” evidence from the state’s own experts that he didn’t break the law because he believed he was in immediate danger, the report said.

The criminal matter was closed on the state level.

Federal prosecutors also reviewed the matter, but concluded there was “insufficient evidence” to charge Dellose or the other three officers with “civil rights violations.”

Keandra McDole is still upset Dellose wasn’t arrested. She led a protest last week, with dozens of people marching through the streets of Wilmington seeking to have the investigation reopened and urging lawmakers to change the use-of-force statute.

Police “take an oath to protect and serve, not aim and kill,’’ she told WHYY News. “He already knew he was going to kill my brother, OK? He was going to execute my brother.”

Denn’s office should have brought charges, she said.

“You never know what the jury is going to say,’’ she said. “Let the people say if he’s right or wrong.”

Keandra McDole said the law gives police too much leeway.

“Technically, in Delaware, the only thing an officer has to say is that he feared for his life,’’ she said. “Then, he can get away with murder.”

Dellose, who also was one of five officers who fired at and wounded a motorist in 2010, did not respond to WHYY’s requests for comment. He left the force in April 2018, but union boss Ciotti said he never returned to active duty after shooting McDole.

‘I didn’t have the gun anymore’

Another shooting mired in ongoing controversy involved Wilmington Cpl. MacColl, one of the four officers who shot McDole.

In February 2019, MacColl shot 18-year-old Yahim Harris as he sprinted from a car that had been reported as carjacked.

MacColl is white. Harris is Black.

MacColl said Harris turned toward him while running in the other direction and “extended his left arm towards him with an object in his hand,” the state’s report said.

MacColl said he thought it was a gun and fired several shots, striking Harris twice in the torso.

Officers found a cell phone in the snow near where Harris collapsed, but no weapon.

MacColl later said Harris asked him, “Why did you shoot me? I didn’t have the gun anymore.”

The report said a surveillance camera shows Harris turning toward MacColl “and extending his arm in his direction.” Harris’ attorney, Aman Sharma, countered that the grainy footage is inconclusive.

“Clearly, the young man is running from police,’’ Sharma said. “There’s not a reasonable way it could be interpreted that he is pointing a firearm, which he doesn’t even have, of course, at anyone.”

Jennings’ office cleared MacColl, ruling he “believed” deadly force was necessary.

Though MacColl was exonerated for the shooting, authorities recently opened a separate investigation into the officer for giving contradictory stories about changing the barrel of his police revolver to improve its firing accuracy.

That revelation led prosecutors to drop carjacking and other charges against Harris.

MacColl left the force after nearly 15 years as a city cop, officials said this month.

Time for a change?

Wilmington activist Coby Owens, who led a peaceful protest this month against police brutality, said Delaware’s law needs to be scrapped or amended.

“Taking away the subjective part’’ of the deadly force statute “and making it more of an objective standard’’ is paramount to holding officers accountable, Owens said.

Owens also called for stronger internal police policies that stress de-escalation tactics and other measures, such as pepper spray, to deal with quarrelsome or combative suspects.

“The use of fatal force should be the very last option,’’ Owens said.

State Rep. Lynn says public sentiment has changed — swiftly and with purpose.

“The murder of George Floyd has brought about a push for societal change and certain endemic change’’ in how police operate and are overseen, he said.

The use-of-force statute is “one of the places we’ve got to start,” Lynn said.

The path to passage might not be easy though. Delaware’s law enforcement lobby is powerful and supported by a handful of former police officers who are in the Legislature.

One is Republican Sen. Dave Lawson of western Kent County, who was a state trooper from 1973 to 1993 and said he once shot a suspect. Lawson, who is white, would not discuss that episode.

“Unless you have served in law enforcement or the military, you have no idea what goes on out there,’’ he said. “And in the matter of a split second, you have to make a decision as to whether that’s a life-threatening situation and you have to respond accordingly.”

Lawson said the subjective standard for police and civilians is “working quite well. I believe it’s more relevant, what the person is thinking, as opposed to some yardstick that is brought about later.”

Democratic Sen. Tizzy Lockman, who is Black and who represents part of Wilmington, countered that the law “is extremely deferential’’ to an officer who “may have made poor choices in aggressively pursuing a suspect.”

“It gives me, as someone representing communities that are often overpoliced, a great deal of concern that we don’t seem in Delaware code to have the opportunity to really to deal with the officer who might be a bad actor.”

Lockman said the current “great groundswell around the movement” for police reform “provides the cover and momentum you need’’ to amend the law.

Jennings had wanted the bill to be considered before the General Assembly session ends on June 30, but that didn’t happen.

Lynn said the bill will be a top priority for him when lawmakers reconvene in January, but fears the drive to change a law that’s been on the books for seven decades might “die down” over the next six months.

“The time to strike while the anvil is hot is now,’’ Lynn said. “The window is open right now. And I don’t know how long it’s going to be open before it’s slammed shut again.”

Show your support for local public media

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.