D.C. cardinal denies knowing of McCarrick sanctions, contradicts pope’s accuser

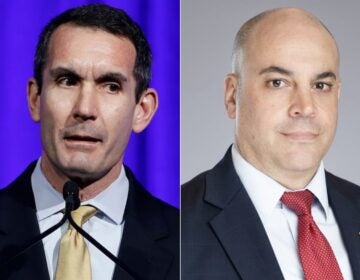

In 2015, Francis, left, talks with Cardinal Donald Wuerl. After serving in Pittsburgh, Wuerl now leads the Archdiocese of Washington, D.C. (L'Osservatore Romano/Pool Photo via AP)

The archbishop of Washington Monday “categorically denied” ever being informed that Pope Benedict XVI had sanctioned his predecessor for sexual misconduct, undercutting a key element of a bombshell allegation that the current pope covered up clergy abuse.

Cardinal Donald Wuerl issued a statement Monday after the Vatican’s former ambassador to the United States accused Pope Francis of effectively freeing ex-Cardinal Theodore McCarrick from the sanctions in 2013 despite knowing of McCarrick’s sexual predations against seminarians.

Wuerl would have presumably known about the sanctions since McCarrick lived in his archdiocese.

The claims of the former Vatican ambassador, Archbishop Carlo Maria Vigano, have thrown Francis’ papacy into crisis.

The core of his cover-up charge against Francis rests on what sanctions, if any, Benedict imposed on McCarrick and what if anything Francis did to alter them, when armed with the same knowledge of McCarrick’s misdeeds.

Vigano, who was Vatican ambassador from 2011-2016, said he had been told that Benedict imposed sanctions on McCarrick starting in 2009 or 2010, after a decade’s worth of allegations of misconduct had reached the Vatican.

By that time, two New Jersey dioceses had settled complaints of sexual harassment and misconduct against McCarrick lodged by two former seminarians. It was apparently common knowledge that McCarrick would invite seminarians to his New Jersey beach house and into his bed.

“The cardinal was to leave the seminary where he was living, he was forbidden to celebrate Mass in public, to participate in public meetings, to give lectures, to travel, with the obligation of dedicating himself to a life of prayer and penance,” Vigano wrote of sanctions imposed by Benedict.

The problem is the historic record is rife with evidence that McCarrick lived a life devoid of any such restriction in those years. He traveled widely, including for Catholic Relief Services, the humanitarian branch of the U.S. church. He celebrated Mass publicly. He traveled to Rome with the entire U.S. conference of bishops for their once-every-five-year visit in 2012 and was even on hand for Benedict’s final general audience in 2013.

In one 2010 video posted on YouTube, McCarrick was shown visiting the national seminary in Haiti that had been damaged earlier by the devastating 7.0-magnitude earthquake. “The boys are still living in tents,” McCarrick said as young Haitian seminarians were shown milling about.

If such sanctions existed, “then McCarrick himself has either somehow forgotten he was under sanction, or he is being woefully disobedient,” said the Rev. Matt Malone, editor of the Jesuit magazine America, who in a series of 13 tweets provided links to news reports, photos and other evidence of McCarrick’s very public ministry in the years that he was purportedly to have retired to a lifetime of prayer and penance devoid of public ministry.

As the archbishop of Washington, where McCarrick lived, Wuerl presumably would have known about any restrictions on McCarrick’s ministry, though it would have actually been up to Vigano and his predecessor to impose and enforce them.

“The only ground for Cardinal Wuerl to challenge the ministry of Archbishop McCarrick would have been information from Archbishop Vigano or other communications from the Holy See,” said a statement from the Washington archdiocese. “Such information was never provided.”

Canon lawyer Kurt Martens concurred.

“Cardinals are exempt from the jurisdiction of the local ordinary,” or bishop, Martens said. “That’s why a nuncio has to step in on behalf of the Holy Father. A local bishop has no authority over other bishops. You can’t control your predecessor.”

The Vatican spokesman didn’t immediately respond Monday when asked to confirm or deny the existence of any sanctions imposed by Benedict. Francis, for his part, declined to confirm or deny Vigano’s claims when asked by reporters on the flight home from Ireland on Sunday.

“I won’t say a word about it,” Francis said, urging journalists to read Vigano’s text and come to a judgment themselves. “I think the text speaks for itself.”

Vigano’s bombshell laid bare how the ideological battle lines drawn between conservatives and progressives over Francis’ papacy have turned into a full-fledged civil war.

“A new episode of internal opposition,” the Vatican newspaper l’Osservatore Romano said Monday of Vigano’s allegations.

Vigano called for Francis’ resignation over what he said was his complicity in covering up McCarrick’s crimes. But if Benedict had the same information and either didn’t impose sanctions on him or didn’t enforce them, Benedict too could be accused of complicity, or at least negligence.

Francis accepted McCarrick’s resignation as cardinal last month, after a U.S. church investigation determined that an accusation he had groped a teenager in the 1970s was credible. Up until that allegation involving a minor, the case against McCarrick had involved accusations that he slept with adult seminarians — a clear abuse of power, but a much less serious crime in the church’s eyes.

Since then, another man has come forward to say McCarrick began molesting him starting when he was 11, and several former seminarians have said McCarrick abused and harassed them when they were in seminary. The accusations have created a crisis of confidence in the U.S. and Vatican hierarchy.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.