A closer look at Race Street Pier

How does our city’s beautiful new pier park hold up for a regular old rainy weekday visit? After a promising first visit on opening day, when the sun was shining, I indulged in a second stroll to Race Street Pier to find out.

First off, the approach seemed even more bleak — hurry up already with the promised Race Street connector! But the park itself looked verdant and inviting, if rather solitary. When I arrived with a friend, only one other visitor occupied the entire acre. By the time we left, several other couples had wandered in.

Under darkened skies, the surprising sweep of the pier seemed still more expansive, and the rolling gray waters more dramatic.

It made even more compellingly obvious the fact that this park is really our version of New York’s new public spaces along the Hudson and East Rivers — and not, as has become conventional wisdom, to the High Line.

Naturally, the comparison with the High Line is tempting — one, because the same designer is responsible for both projects, and two, because Philadelphia so desperately wants a calling card adaptive re-use park of its own. But here, on the pier, it’s the water that’s the star attraction. On the High Line, it’s the height.

During my half hour in the park on this dreary day, every visitor seemed drawn to promenade toward the prow-like end of the pier, the better to gaze yonder over the water. The amphitheater seating positions you to do so, as do the benches. The sheer length of the pier encourages you to keep walking.

But along the way, it’s the design elements that make the park successful. Rusted steel planters, for example, easily bring to mind the solid industrial feel of, yes, the High Line. (Although their lush perennials are pretty and welcomingly mature, they’re not so striking as the marshlike native grasses and almost weedy authenticity of those interwoven into the High Line.)

Wharf drops, covered with mesh grating, and with a specific piece left semi-exposed to reveal the murky water and rotting innards of the old infrastructure, too, are very nice touches.

Railings crafted of steel and wood, and similarly fashioned benches, have become almost too-familiar pieces of the urban park vocabulary, but they seem right here. Fabricated materials — such as the reclaimed plastic and wood decking, and the grey brick-like paths — are by contrast a little too new-looking. With age, they too may take on a patina — though no doubt their very resistance to wear is their chief selling point.

The park’s lighting is a definite architectural element, and very present. It’s there in the 200 LED solar light blocks embedded into the brick pavers, there under trees, there along the railings, and there in the double-headed light stanchions.

Once in the sunshine, once in the rain; next up for me: the park after sunset.

Because it’s at nighttime, I suspect, that the park’s spectacular situation will really shine. Then, the wonders of and on the river and the Camden shoreline will recede, and those of the soaring Benjamin Franklin Bridge will come forth. In daylight, its looming presence is a treat, in the evening, will it be even more thrilling?

A few quibbles. Floating piles of lumber, garbage, and general muck flank both sides of the pier, along the Columbus Boulevard embankment. On the north side, the duck boats even drive right through the gunk. This sort of thing mars the entire riverfront, but here it’s particularly unseemly. Shouldn’t Ride the Ducks or someone look into cleaning this up?

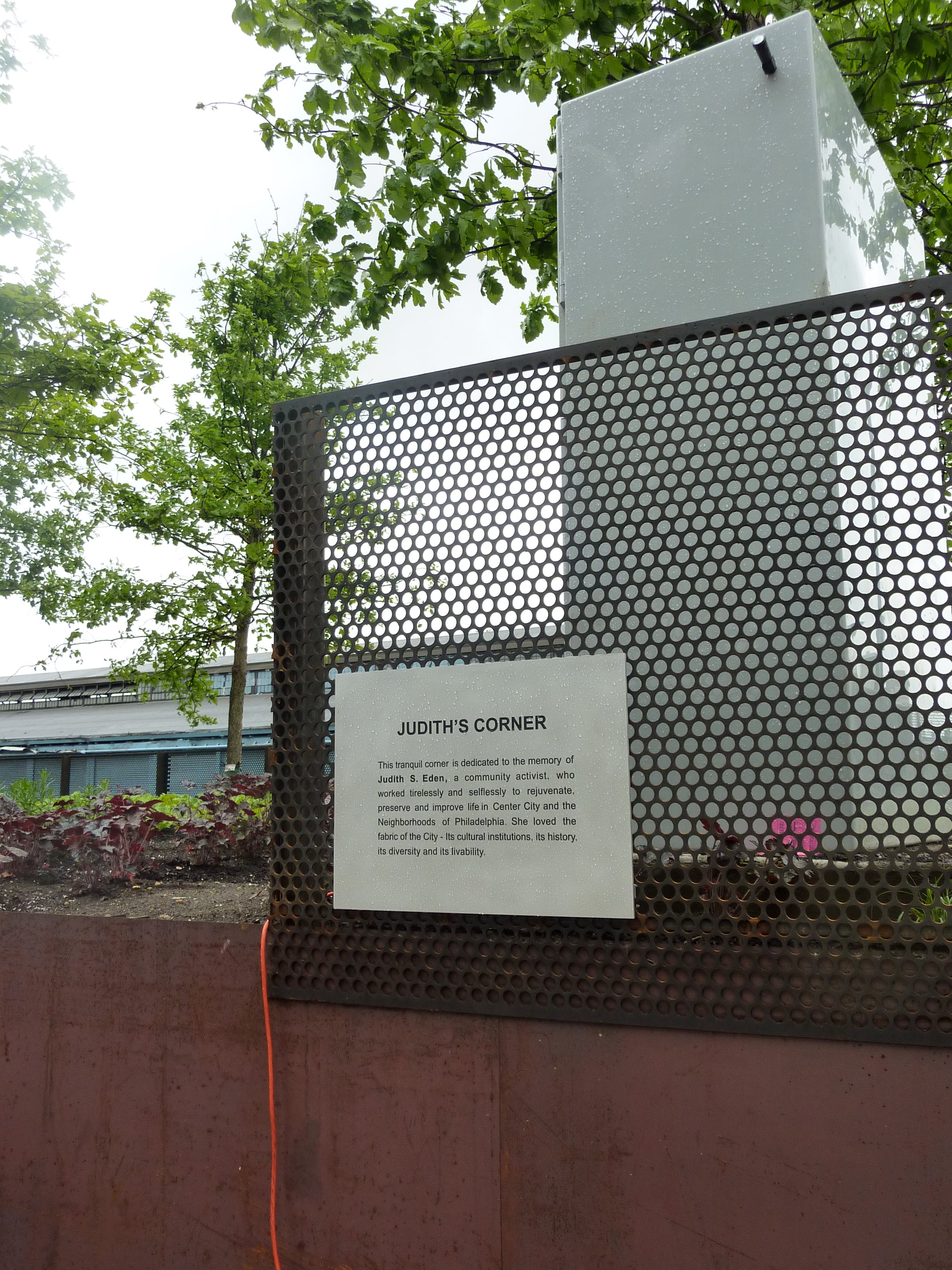

At the entry to the park, a “tranquil corner” — marked by a plaque — has been dedicated to community activist Judith Eden, who died in 2008. But sitting near traffic and bearing no distinction other than an electrical box (!), this inaccessible spot is neither tranquil nor really a corner. In fact, it’s unclear exactly what spot is being referred to. Instead of being raised on a slope above the ground, shouldn’t it be placed somewhere else, so that visitors can sit or stroll in seclusion?

On the other hand, the rest of the park “thank you’s,” are glaringly in-your-face, with too-large signs placed under trees and along benches. Unremittingly corporate or politically correct, they recognize the contributions of unions, civic associations, contractors, and even the GLBT community! It’s all too much.

Finally, the question of whether there’s a there there. The High Line, as remote as it is, provides a way to move through town. The Hudson and East River parks, in running alongside the rivers, do the same. By simply leading us to the water and back away again, no matter how charmingly, this finger pier cannot do that. It needs a little more of a reason for us to want to come back and back again.

Fireworks viewing, sure. Maybe some music. But what would really work is a tie to the beautiful — and recently repainted — Pier 9, the park’s southernmost neighbor. It’s so close, waiting, waiting. With its roll-up gates and big openings, the pier is just about ready-made for ice cream shops and farmers markets and espresso stands.

Festival piers are tired, but something like the Ferry Building makeover in San Francisco might be more like it. An architect friend of mine, Larry Weintraub, even envisions a walkway spanning the gap between the two piers. What a brilliant solution — and a much easier thing to accomplish than, say, the pat condo conversion.

For now, the park may gift us with a fabulous use for a previously rotting asset. But has it presented us with any more reason to get down to the river than we had before?

Contact the reporter at jgreco@planphilly.com

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.