City asks public for preservation perspectives

On Tuesday night a couple hundred Philadelphians squeezed into the upper floor of the Independence Visitor Center to ruminate collectively about historic preservation.

The meeting is the work of the Kenney administration’s Historic Preservation Task Force, an unwieldy group of several dozen interested stakeholders that is attempting to hammer out a clear direction for preservation policy.

There have already been several meetings of the official task force, but Tuesday’s was the first and only meeting meant for mass public partcipation. (All of the task force meeting are open to the public, and some will be held in neighborhoods to make them more accessible.) At least 164 people signed in, and the room probably held as many as 200.

Although the usual suspects appeared—those activists who regularly show up to Historical Commission meetings—unfamiliar faces filled the room as well.

“It’s nice to not just see the usual professional crowd, but a lot of neighborhood people,” said Paul Steinke, executive director of the Preservation Alliance for Greater Philadelphia. “There’s geographic diversity, but there’s also still a lot of work to be done in reaching many neighborhoods.”

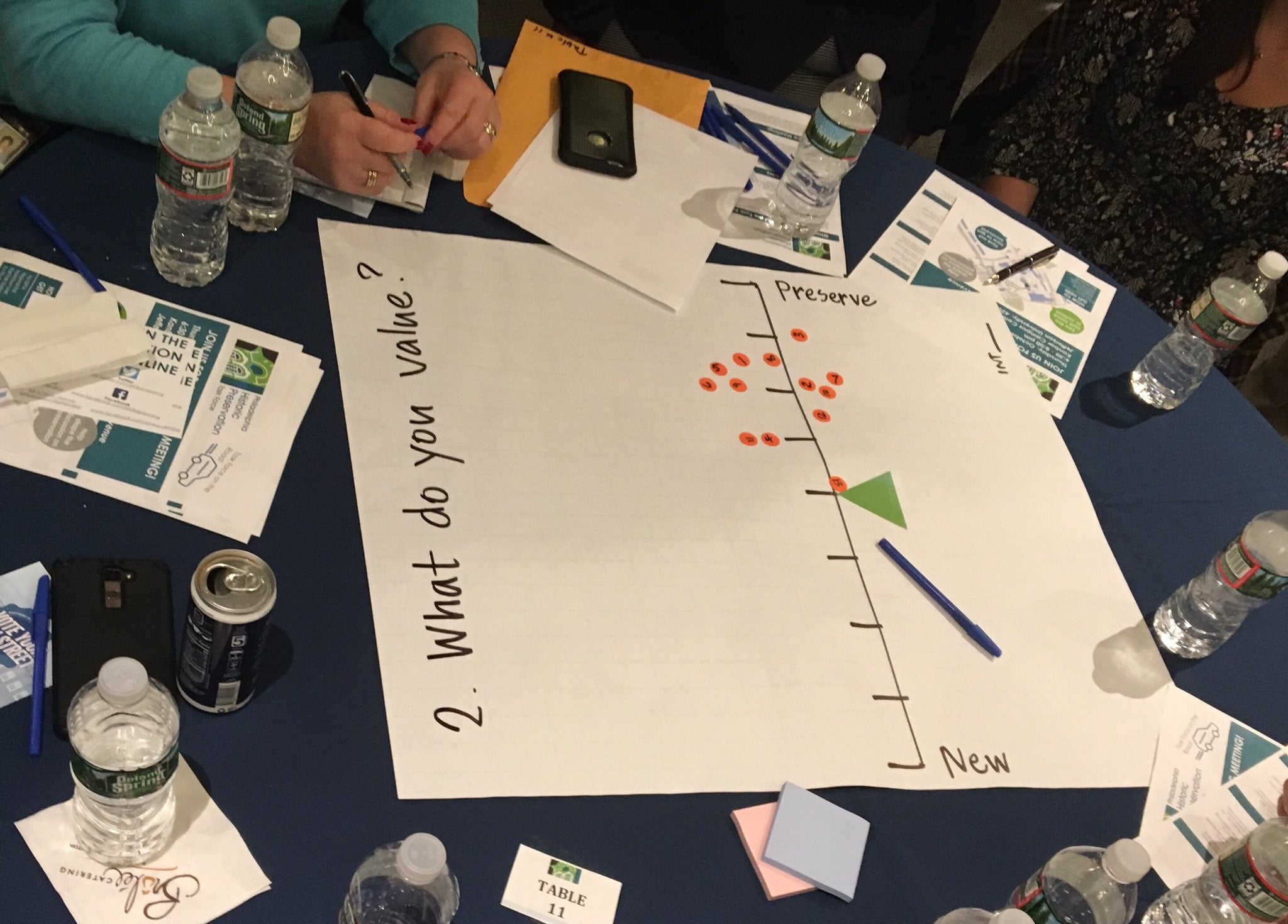

Although the attendees reached beyond the dedicated activist base, the crowd still had a strongly preservationist bent. The 17 breakout groups were asked to show their preference on a poster-sized graph offered at each table. Each participant was given a sticker to mark whether they favored hardline preservation on one end or an entirely newly built environment on the other, with various gradations of feeling in between. Among the couple hundred participants, the sticker votes on the “new” half of the scale could be counted on two hands.

“I think there’s two reasons for that,” said Laura Spina, community planner with the Philadelphia City Planning Commission, who orchestrated the format of the meeting. “First, people who are passionate about preservation are the ones who are here. And second, we tried to reach out to the development community, who might have had a more balanced view of preservation. But unfortunately, we don’t have a lot of representatives from that constituency here tonight.”

Although numerous representatives of the real estate and business communities sit on the task force, one of the only obvious representatives of those interests present was Matt McClure of Ballard Spahr.

“The kinder gentler, task force members are leading them,” said McClure, when asked why he wasn’t one of the taskforce members leading a breakout session. “Actually, I just wasn’t able to get to the trainings on time.”

The Preservation Task Force received some criticism for a lack of racial diversity initially, and the organizers of Tuesday’s event attempted to prevent similar critiques of its big meeting for the general public. It received heavy promotion at recent district planning sessions in North and West Philadelphia. Flyers were printed in Spanish and Chinese and distributed to the appropriate community groups. Nonetheless, the crowd was largely white and few non-English speakers attended (although, notably, a prominent public meeting occurred in Chinatown at exactly the same time).

Attendees were asked to mark their neighborhoods with green stickers on a map near the entryway. Most of the attendees were from either Center City or University City, with a healthy contingent from the northwestern neighborhoods as well.

“We had to pick a central location because this is the one public meeting,” said Spina. “Obviously more people will come to a meeting when it is in their backyard.”

There will be future Task Force meetings open to the public in neighborhoods outside Center City, although none with public participation components of this magnitude.

The leaders of the breakout groups guided attendees through a series of exercises. First, they asked for perspectives on what makes Philadelphia unique. Then they conducted the exercise measuring the value of preservation versus newer buildings. Finally, participants were asked to define historic preservation as a concept.

Spina said that the point of the exercises is to get people to think of preservation beyond their neighborhood or their favorite building. The focus should be on the view from 30,000 feet, she said. What are the assumptions we have about historic preservation? Is it exclusive? Is it only for the rich? Only for white people? The task force asked attendees to unpack the very concept and elucidate what, broadly, should be preserved about Philadelphia.

“It was really valuable and it gives us an opportunity to have a voice,” said Ramona Rousseau-Reid, of Eastwick. She said the process reminded her of public meetings held by the Redevelopment Authority about the reuse of city-owned land in her historically marginalized neighborhood. She hopes to use the connections made at the event to help empower her community in the planning struggles to come.

Some attendees were disappointed in what they felt to be a lightweight exercise, which didn’t leave many practical avenues for citizen involvement moving forward.

“To me, it felt kind of inappropriate for the audience,” said Starr Herr-Cardillo, graduate of the University of Pennsylvania’s master of historic preservation program. “I think people were expecting to be able to voice their frustrations or feelings about the state of preservation in Philly and this was sort of a dumbed-down feel-good exercise.”

Most participants PlanPhilly spoke with felt broadly, fuzzily positive about the exercise and expressed hope that their preferences would be reflected in the task force’s work moving forward. But many of the older hands, who have been involved in the field for decades, were measured in their feelings about the meeting and the larger efforts of the task force.

“I’m hoping this newfound interest on the part of the city does mark a turning point,” said Jed Levin, a professional archaeologist, who’s worked in the city for decades. “This is the best opportunity I’ve seen since being involved here in Philadelphia. But that’s faint praise, because there’s been relatively little sustained interest in reconsidering how we preserve, or don’t, in this city.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.