How to explore Cape May’s overlooked Black history

From Harriet Tubman’s time in the shore town to Freedom’s Corner and a thriving Black business district, Cape May’s history is worth exploring this Black History Month.

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

Cape May’s ornate Victorian homes and quiet winter streets feel like a place for leisure. But beneath the gingerbread trim and ocean views lies a chapter of American history that many have overlooked. For visitors from the Philadelphia region seeking a meaningful Black History Month experience this February, Cape May offers a weekend steeped in stories of abolition, community resilience and culture, according to local experts.

Why Cape May for Black history?

Cindy Mullock, executive director of the Harriet Tubman Museum of New Jersey, noted that Cape May has a deep commitment to preserving and restoring places once dismissed as “blighted.” As long-overlooked histories have come to light, the community has worked to reclaim both the buildings and the stories they hold, she said.

“What is the underrepresented history in your own backyard?” Mullock said. “Cape May is a registered national historic landmark and recently updated its national historic landmark registry to include specifically African-American history.”

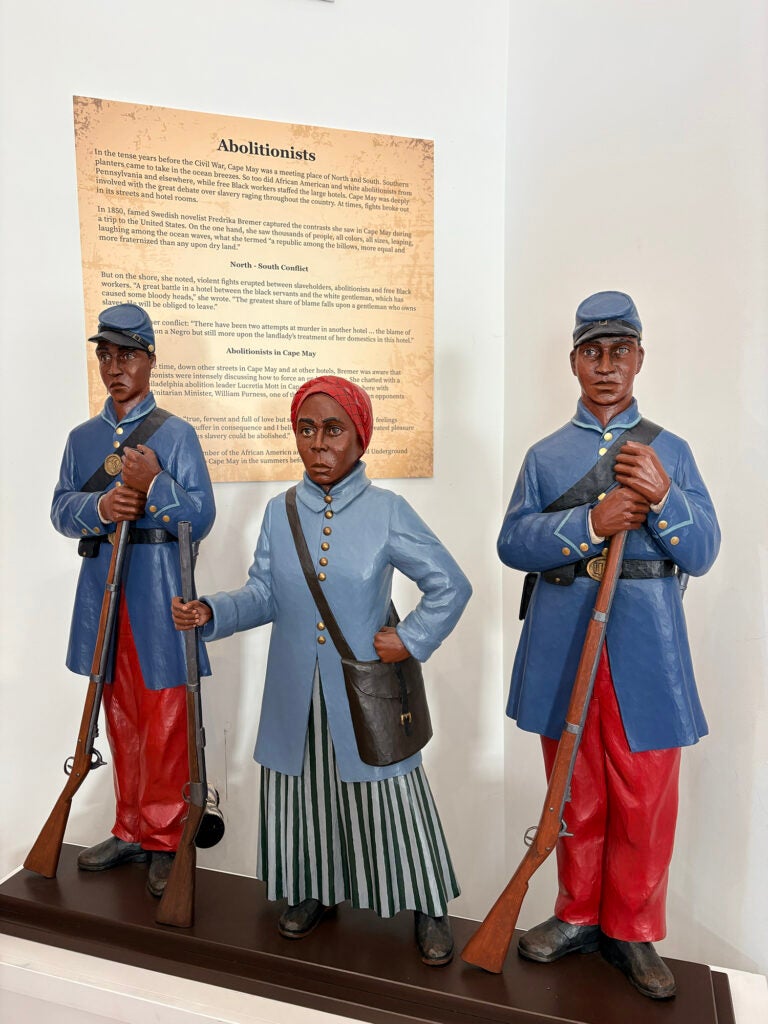

Cape May emerged as an important setting in the movement to end slavery, drawing prominent abolitionists and reformers who spent their summers in the shore town, Mullock said.

Harriet Tubman lived and worked in the town in the early 1850s, according to museum archives. After leading freedom seekers to Canada, Tubman returned to Cape May to earn money working in hotels and private homes. Abolitionist Franklin Sanborn later wrote that in the fall of 1852, she traveled back to Maryland from Cape May and helped nine more people escape enslavement. She spent two additional summers in the shore town.

“Cape May is an incredible source of so many stories and narratives of all of these characters who held such prominence, and were deeply engaged in the struggle for freedom and equality, and to abolish slavery,” Mullock said.

Must-see attractions during Black History Month

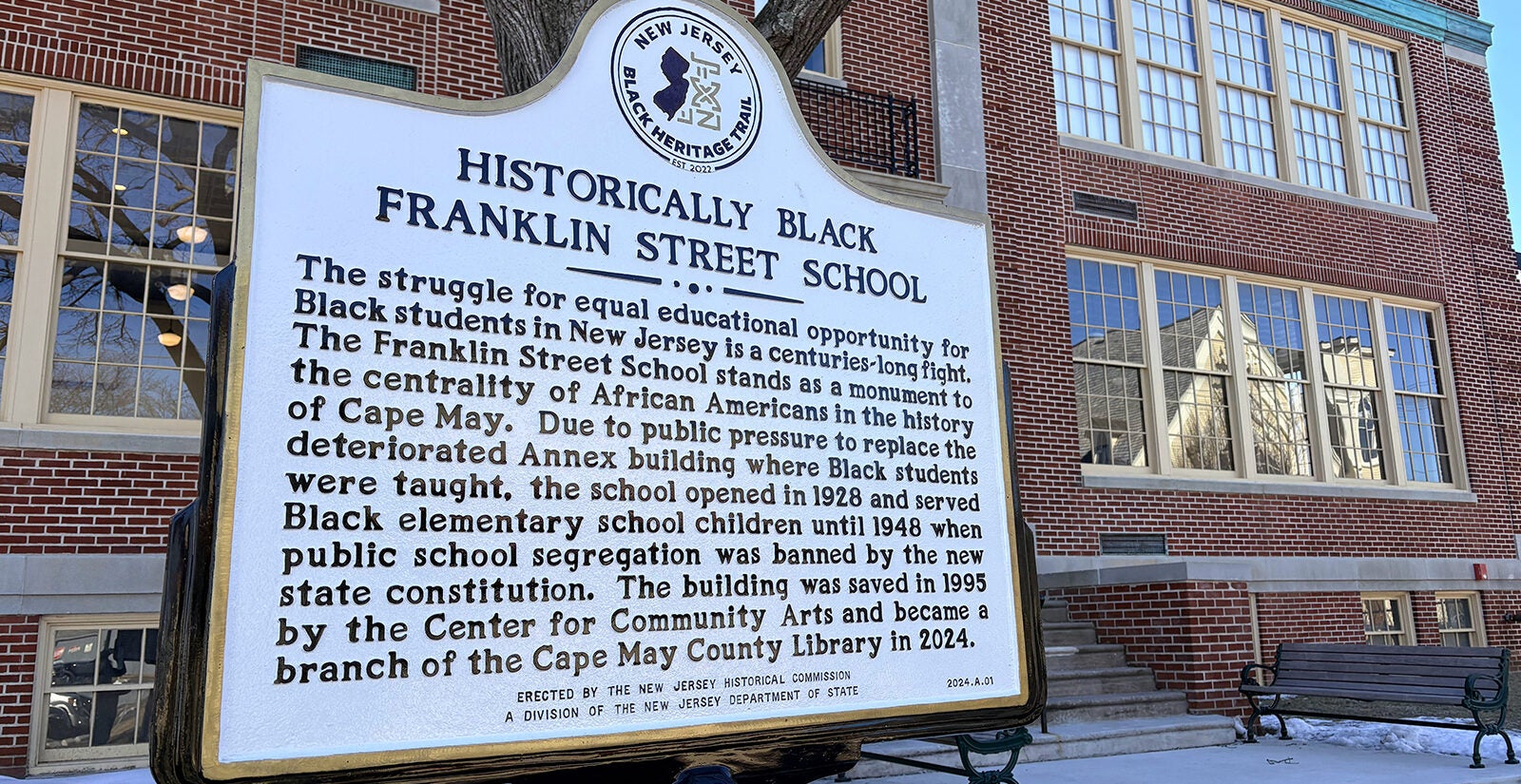

Visitors can begin at the Franklin Street School, located at 720 Franklin St., which was once a segregated school for Black children and is now part of the Cape May Library System. The city of Cape May, in collaboration with the New Jersey Historical Commission, unveiled the first New Jersey Black Heritage Trail historical marker. The marker recognizes the Franklin Street School and Cape May’s Black community’s determination to secure equal educational opportunities for their children during segregation.

Also recognized as a trail site is the nearby Macedonia Baptist Church, a short walk from the school and now home to the Harriet Tubman Museum of New Jersey. Across the street from the museum is the Smith house. Stephen Smith, the owner, was the richest black man in the United States at that time, and this was his summer home.

For Black History Month, the Emlen Physick Estate’s Carroll Gallery is hosting “Black Legacy of Historic Cape May: Unexpected History,” an exhibit highlighting Black residents, leaders and visitors.

“The town hosted influential figures such as Marian Anderson, Paul Robeson, W.E.B. Du Bois, and Martin Luther King Jr., leaving a legacy of culture, activism, and resilience,” Cape May Mac said in a press release. The exhibit runs through April 12.

Additionally, on Feb. 16, the Black Legacy in Historic Cape May Trolley Tour will offer guided storytelling across town. The Center for Community Arts is offering a self-guided African American Heritage Walking Tour with 10 stops, approximately 90 minutes.

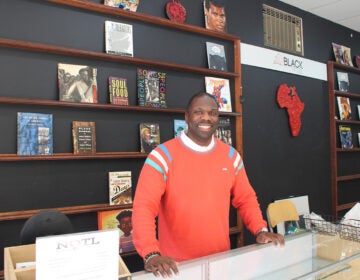

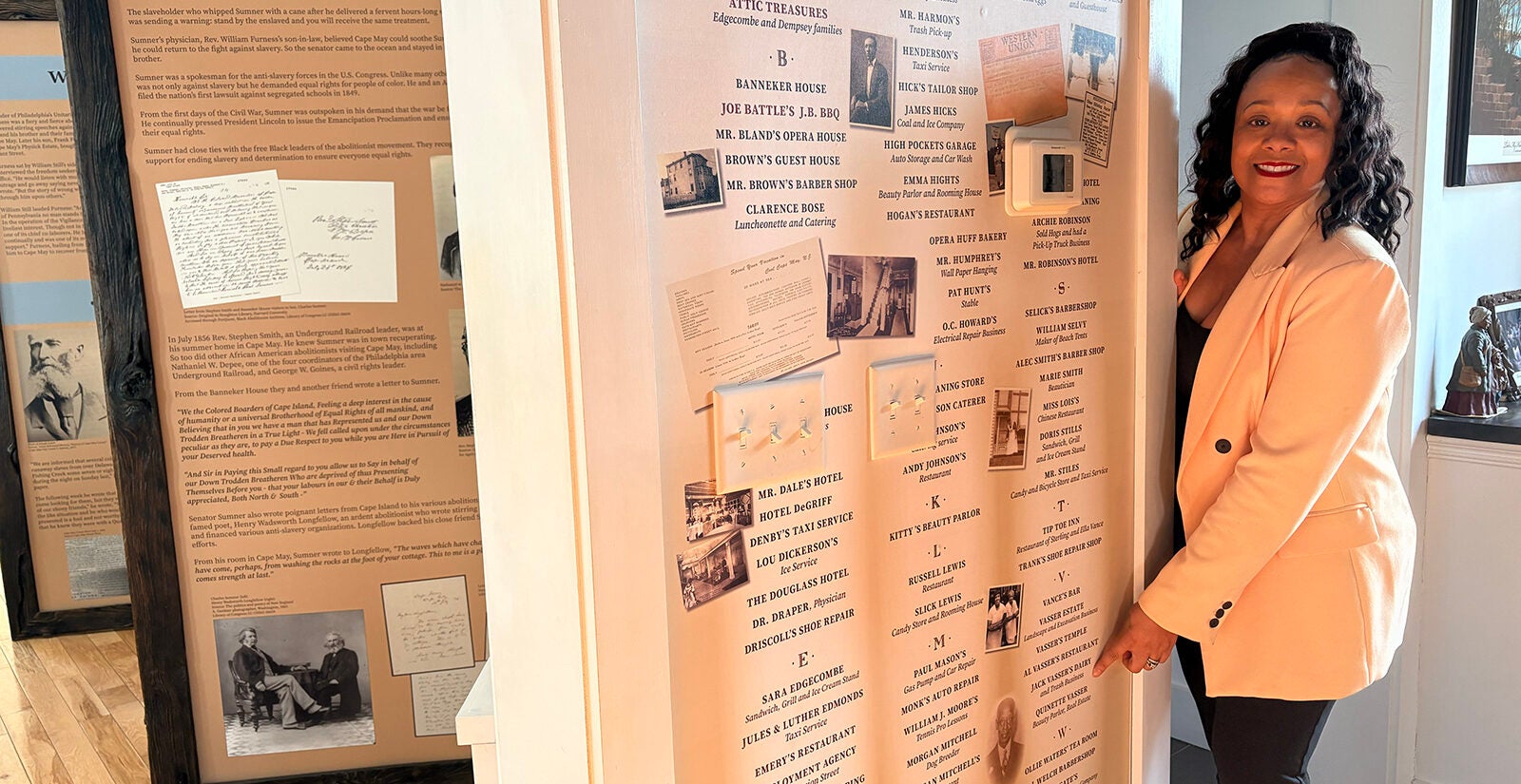

Visitors can also learn about the roughly 70 Black-owned businesses, which were part of the once-thriving network of Black entrepreneurship and homeownership, Mullock said. She said the Lafayette Street corridor, especially the intersection of Lafayette and Franklin streets known as Freedom’s Corner, served as a hub of Black community life and activism during the late 1800s, and now offers visitors a tangible connection to Cape May’s Black history.

Visitors can also eat at Freda’s Cafe, one of the last Black-owned brick-and-mortar restaurants in Cape May. The restaurant has become a community fixture, offering scratch-made dishes.

“As someone born and raised right here in Cape, I can tell you this little seaside town is more than just beaches and Victorian houses,” said Quanette Vasser-McNeal, the community outreach director for Cape May County and president of the Cape May County Chapter of the NAACP. “Cape May has one of the oldest African-American communities in the country. From the early days of the resort, Black workers built hotels, cooked in kitchens and created businesses that helped Cape May come alive.”

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.