Camden community activist Frank Fulbrook dies

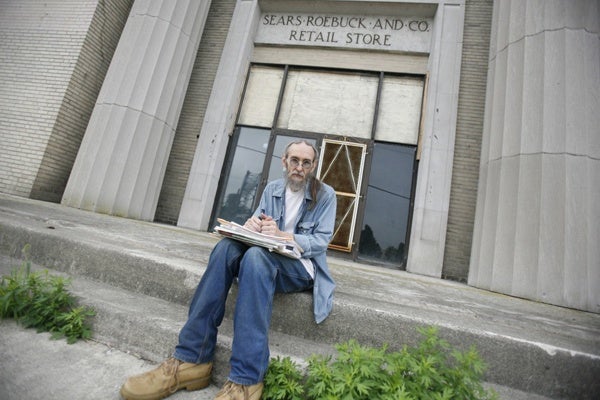

On the rare occasion when longtime Camden activist Fulbrook wasn’t attending a public meeting or a filing court motion to force the city’s hand toward an issue he championed, he could often be spotted hunched over a steering wheel, slowly driving his aquamarine Geo Metro around the Cooper Grant neighborhood where he lived — keeping a protective eye over its relatively leafy streets.

Today, Fulbrook’s signature vehicle sits immobile outside the five-unit apartment building he owned, its back driver-side window covered in residential parking stickers that date to 1996.

Fulbrook, who spent almost all of his 60-plus years in Camden, died yesterday morning at Cooper University Hospital. After fighting a lung infection that had kept him from actively engaging both politically and socially for a full year, he passed away with a friend by his side.

Mayor Dana Redd released a statement calling Fulbrook, “one of (Camden’s) most dedicated and committed advocates.”

Referred to as “one of the most recognized non-elected figures in Camden” by the president of his neighborhood association, Fulbrook made countless friends and enemies as he sought to influence policy. It was a passion he pursued tirelessly by sitting on volunteer boards, speaking fervently at meetings — armed with reams of paperwork and an elephant-like memory of history – and filing lawsuits when the first two activities failed to bring about the decisions he desired.

Most notably, lawmakers, lawyers and fellow citizens remember his efforts to overturn a ban on business curfews; block unsightly billboards, decriminalize marijuana and clear the way for a dispensary within city limits; and, recently, stop the demolition of the historic Sears building that stood in the way of the development of a business park spearheaded by Campbell Soup Co. In October, the city may hold a referendum on an issue Fulbrook, who considered himself an independent Democrat, strongly advocated for but had grown too weak to continue fighting for: non-partisan elections.

Democratic state Senator Donald Norcross, who represents Camden, said, “Frank’s advocacy for the city was second to none. He’s been a fixture here for literally my entire life.”

Over the years, the man who described himself as an “industrial hippie” — who wore a uniform of workboots and jeans, sported a thin grey ponytail and hadn’t shaved since 1969 — ran unsuccessfully for mayor and city council. A “Fulbrook for Mayor” sticker still decorates a window of one of the apartments he rented to Rutgers-Camden students and young professionals.

In a 2010 audio slideshow produced by WHYY, Fulbrook explained his activism by saying, “I feel a responsibility to do whatever I can to improve the city. So I go to meetings in neighborhoods across the city, not just my own neighborhood, to try to help people achieve their goals.”

Fulbrook, did, however, look after his own neighborhood as well. In 1982 he founded the Cooper Grant Neighborhood Association (CGNA), which remains the city’s oldest in continuous operation. As president, he helped secure the development of Camden’s first market-rate housing in at least 30 years.

Officers of the organization released a statement saying, “We remember his relentless advocacy for community residents and his conviction in the power of grassroots efforts. He drove and walked the neighborhood regularly, believing that involved and proactive citizens make a community a better place.”

Fulbrook’s activism also reached down to the personal level. Before Rutgers law student James Campbell moved into one of Fulbrook’s apartments three weeks ago, his landlord had already shown him trust and leniency.

“Money is really, really tight right now, so even though my deposit was due in June, he was like, ‘Get it to me when you get it to me.’ He said the same thing about my first month’s rent,” he said.

This, despite the common assumption that Fulbrook wasn’t exactly flush with wealth. Childless and never married, he supported himself with rental income, occasional stipends and salaries collected from non-profit organizations he supported, and by lecturing and assisting with urban studies classes at Rutgers.

“I think that he donated any money he won from legal settlements to charity,” said CGNA president Jon Latko. “I don’t think he kept any of it.”

Indeed, a Philadelphia Inquirer story published in 2004 chronicles $129,000 worth of donations Fulbrook had distributed to community groups through his now-defunct Camden Neighborhood Revitalization Corp., which he launched with money from a settlement he negotiated over the undesirable placement of a billboard in North Camden.

Said Fulbrook in the WHYY production, “There’s an old saying that means a lot to me: If you’re not part of the solution you’re part of the problem.”

Fulbrook is survived by his mother.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.