The bottom rung of American education: Stories from an adult literacy class

Adult education receives few dollars and little attention. For a look at this oft-forgotten world, we spent two months with Philly adults still learning to read.

Listen 5:39

Sandie Knuth with student Joel Newton (Avi Wolfman-Arent/WHYY)

At the bottom rung of America’s education system, you will find someone like Sandie Knuth.

Knuth teaches English for adult learners on the 10th floor of a Center City office building, in a room of carpeted plainness that suits the invisibility of its inhabitants. The students in Knuth’s class are varying levels of illiterate — placed here because an entrance test found they read below a third-grade level.

They’re here because they think — despite years of setbacks and stacked odds — they can earn the basic education promised to all Americans. Knuth’s task is to set them on the journey toward that distant goal.

Class begins on a Wednesday in April at 5:30 p.m.

At least that’s when it’s supposed to begin. There’s a 10-minute grace period for students to arrive — and about a 10-minute grace period informally tacked onto that grace period for those who straggle in even later.

As the 25-year-old Knuth waits for everyone to show, she scribbles a question on the whiteboard.

What do you hope to get out of class?

By 6 p.m., five students have arrived. The last of them is 41-year-old Katrina Williams, who swaggers in with sunglasses on, earbuds in, and a large plastic cup full of Dunkin’ Donuts coffee.

After a boisterous hello, she pulls out her pencil.

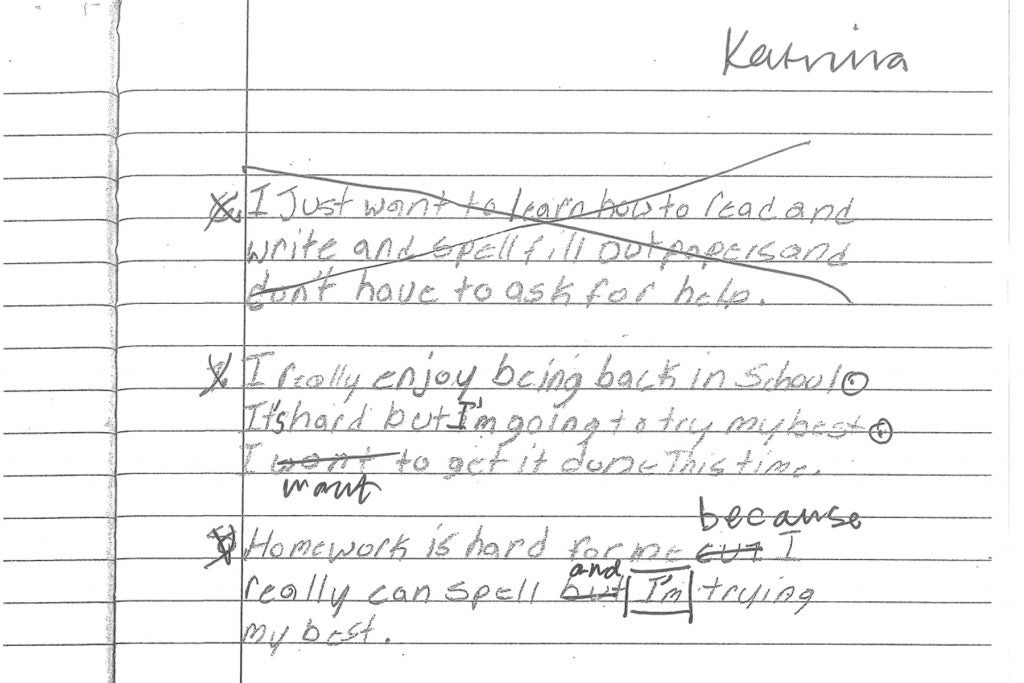

I Just wont to learn how to read and write and spell fill out papers and don’t have to ask for help

I really enjoy being back in School It hard but im going to try my best I wont to get it done This time.

Homework is hard for me cuz I really can spell but Im trying my best.

Although the numbers and faces fluctuate from week to week, the five who’ve shown up on this first day will form the core of the class. All have a common goal: to earn their GED. This class is step one — the furthest point from a faraway destination.

Nationwide, about 1.5 million adults are in state-funded adult education programs, a number that’s fallen sharply since 2000. Over the same stretch, federal funding for adult ed has declined about 8 percent when adjusted for inflation.

This is not because every adult can suddenly read. In Philadelphia alone, an estimated 245,000 adults lack “basic” prose literacy skills, meaning they’re not even capable of parsing a television guide.

Philadelphia has exactly 569 classroom seats for adults who aren’t proficient enough to tackle high school-level work. That’s one opening for every 430 low-literate adults.

Across the state and country, policymakers preach the value of early intervention. There are new pre-K programs to boost kindergarten readiness and warning systems that identify wavering middle-school students. An ounce of prevention, the saying goes, is worth a pound of cure.

But what’s left over for the sick?

Relatively little, it seems. Pennsylvania spends just $12 million on adult and family education, $6.5 million less than it spent a decade ago and about 1/500th of what it spends on basic K-12 education. Nationally, the typical adult education program spends roughly $200 per student per year, according to researcher Steve Reder.

| Fiscal Years | State Funds (In Millions) |

| 2007 | $18.5 |

| 2008 | $23.4 |

| 2009 | $23.0 |

| 2010 | $17.6 |

| 2011 | $14.6 |

| 2012 | $11.7 |

| 2013 | $11.7 |

| 2014 | $12.1 |

| 2015 | $12.1 |

| 2016 | $12.1 |

| 2017 | $12.5 |

| 2018 | $12.1 |

Adult education in Philadelphia is less a school system than it is a federation of do-gooders. The city had made some novel efforts to systematize adult ed by creating central intake points where prospective adult learners can be tested and placed. But there is no bureaucratic body that disburses money, promulgates rules, and shapes curriculum — at least not to the extent a school district does.

The work itself falls on nonprofits such as the District 1199C Training and Upgrading Fund, which is tied to a union representing hospital and health care workers. Last fiscal year, District 1199C received about $740,000 from the state to educate approximately 555 students, whose skills ranged from high school-level to barely literate. The union pays most of its instructors, but, in order to extend its reach, District 1199C recently recruited volunteer tutors to work with students who couldn’t test into its its “level one” course.

‘Job versus no job’

That’s where Sandie Knuth and her students come in.

The handful of students in Knuth’s class are here to begin their ascent of the adult education ladder. From this lowest step they can move to level one. From there, another three classes stand between them and actually sitting for the GED test. Though the program doesn’t have precise records, administrator Lynette Hazelton tells me dozens of students have entered 1199C’s program reading below a third-grade level over the last two years and none of them have yet earned a GED.

But let’s imagine, for a moment, that one of these five students will be the first to make it all the way out of the educational basement. And let’s imagine they are then among the 63 percent of test takers who actually pass the GED.

Where then will they be? What exactly is a GED worth?

The students in Knuth’s class believe it will be their ticket to stable employment. They want to be nurses, medical assistants, and nannies. They want something that will distinguish them in the ceaseless hunt for good wages.

Hazelton considers the GED a passport into the formal economy. High school equivalency in hand, a worker getting paid cash to clean houses can become, say, a hospital cafeteria worker and earn the relative stability and protections of an aboveboard job.

“I’m not talking about jobs that are going to put you solidly in the middle class,” Hazelton says. “I’m talking about job versus no job, job versus under-the-table job.”

Yet, years of research suggest a GED doesn’t do much for job prospects. A 2010 review of the literature found “minimal value of the certificate in terms of labor market outcomes.”

And so here we are at the bottom of the adult education ladder, with a group of students still years away from earning a credential of questionable worth.

This would be a bleak exercise if it weren’t for the people doing it — their resolve, their foibles, and their enduring belief in something better.

These teachers, administrators, and students live in the lowest, most forgotten valley of the education landscape. These are their stories.

Baby learning to crawl

The first day of class is Anna-Gaye Johnson’s 82nd day in America. She is 35, the oldest of seven and the mother of three.

She came to Philadelphia in late January from northeastern Jamaica, leaving behind her children and any semblance of stability.

“Coming here, it’s like baby creeping, like baby just learning to crawl,” she says in a hushed lilt, which comes out at gun-burst speed and golf-clap volume.

Born in the rural highlands of Portland Parish, Johnson’s formal education ended when she was 12 and took a job picking coffee beans for about $10 a day. Her family needed the money, and none of her siblings were old enough to contribute.

“It was not much,” she says. “But I’m a person who like to work.”

In America, she figured she’d do just that — work, make money, and send for family. But she soon found even low-wage employers — like a family looking for a nanny — tended to ask for a high school diploma. When class begins, she’s living with her brother’s family in the West Philadelphia neighborhood of Overbrook, sharing a bedroom with her teenage niece.

She’s set a goal: By the end of 2018, she wants to have her own place with three bedrooms — one for each of her children. To get there, she believes, she’ll need her GED.

Repetition

About half way through the first class, Knuth asks the students to come up with a set of class guidelines she calls “community agreements.”

The students throw out a series of platitudes about hard work and cooperation, which Knuth dutifully writes on the board.

Ask for help.

It is what it is.

Think of the positive. Not the negative.

Midway through the exercise, Christopher Johnson raises his hand and blurts out:

“Repetition.”

“Repetition, practice,” Knuth calls back to him, as she turns to the white board.

Johnson repeats word three more times, in a clipped monotone that makes him sound like he’s short-circuiting.

“Repetition. Repetition. Repetition.”

Johnson, 22, is the youngest in the class by more than 10 years, and the only male. He’s also the only person here with a high school diploma, which he earned in 2013 from Imhotep Charter School in Northwest Philadelphia.

Johnson speaks under his breath, with a perpetual snarl that makes him sound like a disgruntled movie trailer announcer. He often responds to questions with a dazed shrug or prolonged silence. When Knuth asks him if he’s seen any good movies lately, he says “yes,” but nothing more.

According to his mom, Johnson was in special-education classes through most of his formal schooling. But she says he doesn’t have any diagnosed disability. When he took an entrance test for the Community College of Philadelphia, they sent him to 1199C.

The idea of school

Before class ends, Knuth talks through the basics of the course, which she says will last 10 weeks. Don’t come to class without a folder, a notebook, and something to write with, Knuth warns. And don’t forget to write your name and the date on each assignment.

Each week will end with a quiz. If students fail the quiz, they’ll have to retake it at the next class. In between sessions, students will receive some sort of homework assignment, usually tied to a reading of their choice. Students are also expected to write 50 paragraphs over the course of the semester on any topic they want.

This course, Knuth later explains, is as much about acclimating to school as it is learning to read and write. She wants the students to study, complete their assignments, stay on task during class, and, most critically, show up. Good habits don’t guarantee a high school diploma, but they won’t complete the long journey ahead without them.

“At this level, so much of what you need to build is just, like, building up basic confidence,” Knuth says.

She also needs to gauge what her students know. And so, the first day ends with a test. Knuth gives the students a short passage on Ellis Island and asks them to circle 15 nouns, underline two verbs, and answer a series of short questions about the content of the article.

Of the five students who take the test, none score better than a 52 percent. Katrina Williams scores a 0.

Happy to be in class

The third week of class begins with an impromptu therapy session.

Williams explains that she missed the prior class because of a hospital stay brought on by her diabetes. Anna-Gaye Johnson’s dad was also in the hospital, battling high blood pressure.

“We could’ve lost him,” she says. “But, luckily, he survived.”

Cynthia Drayton, a middle-aged woman from Trinidad and Tobago, tells the class she couldn’t make it last week, either, because she’s feeling overwhelmed. Drayton works as a nanny for a Main Line family, and she’s been pulling extra hours lately to accommodate the family’s go-go schedule.

She keeps saying she feels blank, and soon tears start streaming down her cheeks.

“You’re doing all for people, but you’re trying to do for yourself. And it still is like a fight,” Drayton says. “And you can’t get where you want to reach.”

Knuth lets the personal stories marinate, careful not to interject. A recent Princeton grad, Knuth is younger than most of her students. She started teaching at 1199C about 18 months ago after attending a four-session prep course.

She was quickly overwhelmed by how little her students knew — and how little she understood about how to help them.

“I have no idea what I’m doing,” Knuth remembers of her first days as a tutor. “I don’t know anything about early literacy.”

But after a year-and-a-half she’s recalibrated her expectations and rediscovered her optimism. She focuses on the little victories. Even if the two-to-four hours she spends each week prepping for class doesn’t lead to any diplomas, there must be a butterfly effect to what she’s doing. Maybe a parent passes some bit of knowledge to his or her child. Perhaps a student gains the necessary confidence to make some pivotal life change.

During class she is irrepressibly boisterous. Her voice — loud and confident — has a halo of positivity around it.

After the emotions peter out, Knuth cuts in with a warm nudge back to the lesson plan.

“We’re really happy you’re in class today,” she says as Drayton dabs her tears with tissue. “All you guys, I’m really happy you’re in class today.”

The writing formula

Class typically starts with a writing prompt followed by a group read-along. About 90 minutes into the two-and-a-half hour session, Knuth and her volunteer co-teacher, Jenni Jones, break the already small class into even smaller groups for intensive writing help.

Distinctions between what the students can and cannot do — what they do and don’t know — follow no discernible pattern. Some read fairly fluidly. But when they trip up, it’s clear they’re guessing — both on phonics and content.

During the third week, for example, Katrina Williams reads aloud from a short story about a girl’s terrible secret.

It begins: “Once there was a girl named Jenny.”

Williams first reads it as: “When there was a girl naturally January.”

But when Knuth asks Williams to identify the verb in the sentence, she immediately responds with the correct answer.

There’s similar, inexplicable gaps in the students’ writing ability. Knuth needs multiple classes to hammer home the concept of end punctuation. Some students trip up on seemingly simple exercises, such has the one where Knuth asks them to circle each example of end punctuation in a paragraph and then say how many sentences that paragraph contains.

Christopher Johnson, by contrast, seems to understand rudimentary grammar. He capitalizes the beginning of his sentences and routinely rounds them off with properly placed periods.

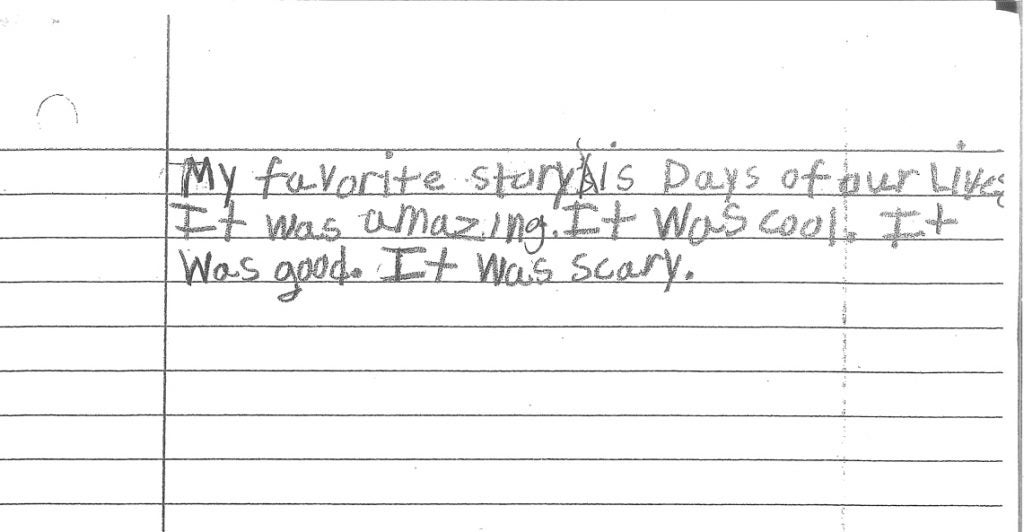

Over the course of the semester, Johnson, because he is so prodigious, is asked to write 100 paragraphs instead of the standard 50. Although the paragraphs display a general mastery of grammar, Johnson sticks to similar topics and structures. He’s concocted a formula for stringing together multiple sentences, and uses it liberally.

One of his paragraphs reads:

“I have a dryer. I use it. I clean it. I wash it. I buy it.”

A second, nearly identical paragraph goes:

“I have a shower certin. I use it. I wash it. I clean it. I dry it.”

When it comes to checking the good-habit boxes, no one does better than Johnson. He always arrives early to class, completes his assignments, and takes tests without complaint.

But is he learning anything? And if he learns little, but develops the proper study skills, is that good enough?

Tired of failing

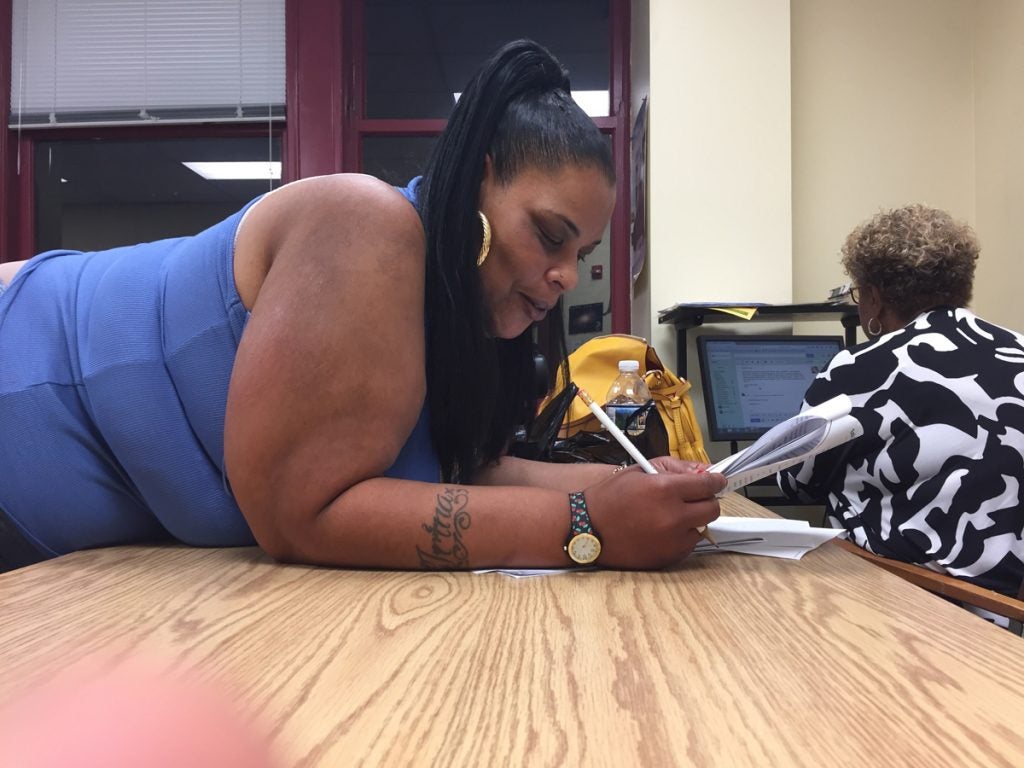

Katrina Williams embodies the opposite problem.

She clearly can pick up new skills, but her combative, combustible personality routinely threatens to stifle progress.

During the fourth week, Knuth, as always, ends class with a quiz. It’s a tough one, Knuth knows it. But Williams can’t even understand the directions written on the quiz, and soon she’s griping about it to Knuth.

“Where the directions at,” Williams asks with a hint of pique.

“Keep reading,” Knuth tells her.

“Why can’t you just say what the directions is,” Williams snaps back. “Why you gotta be difficult? You just gotta be difficult.”

A couple minutes later, Williams is still on the subject. She keeps asking for help interpreting the directions, and Knuth keeps telling her to read them herself. Soon, their back-and-forth is the center of attention.

Williams finally slams her pencil down and trudges through the test, on which she eventually scores a 23 percent.

But as class dismisses, Williams continues to snipe at Knuth.

“I don’t want you to feel angry,” Knuth explains. “I want you to feel it’s OK to fail.”

Williams shoots back: “But if you get tired of failing, you get tired of failing.”

You hate not knowing

Lynette Hazelton, the program coordinator with 1199C, is well aware of this tension. Students in basic adult education, like all students, need to learn resilience. But they can also be especially sensitive to setbacks given their educational backgrounds.

“They have been faced with so much failure all their lives that you really don’t want them to have another failure,” she explains.

Katrina Williams grew up in Oak Lane, a middle class neighborhood on Philadelphia’s northern edge. Her dad worked at a factory in Roxborough and her mom was a nursing assistant. She recalls a fairly typical childhood.

School, though, was a constant struggle. She couldn’t seem to retain what she learned, and she spent most of her years in special-education classes. By the time she entered Martin Luther King High School, she still couldn’t read, and she was, as she puts it, tired of failing.

“You just don’t want no parts of it,” Williams says of school. “You just run.”

She stayed through 11th grade, cutting class about as frequently as she attended. Williams says eventually the school expelled her.

When she was 19, Williams had her first son. A couple years later, her son’s father hurt himself and lost his job. With that, Williams lost her primary form of income, child support checks. She says she spent about a year with her young son at a shelter in West Philadelphia, but can’t recall the name. When the child support checks started flowing again, she moved out, eventually to the Frankford section of Northeast Philadelphia.

Williams now has two sons, and a longtime partner she calls her “man” (“not my boyfriend,” she insists). One of her sons recently graduated community college and enrolled at Bloomsburg University. Her other son, she says, is just like her — fiery-tempered and averse to school. He recently wound up in juvenile detention after a scuffle with a high school security guard. Williams visits him every week.

She has both of her sons’ names — Shalih and Shahib — tattooed across her left arm in large, curved letters. She came to 1199C for them, not because she’s especially crippled by her inability to read.

Sure, it makes life difficult at times. But she’s always able to cope. Her man fills out forms. When she needs to get off the bus at the right stop, she simply tells the driver to alert her so she doesn’t have to read street signs.

“There’s a way around everything,” she says.

There wasn’t, however, a way around the shame she felt when she couldn’t help her kids with homework. And there wasn’t a way around the fact that she couldn’t set the example she wanted when her boys were younger.

“How I can tell him to do something right if I can’t do it the f*** right,” Williams asks.

Williams has attended four different adult education programs at some point over the last 20 years, she says. But she’s never stayed long enough to get her GED. It’s the same struggle she’s always had: She wants to learn, but she hates not knowing.

“You get into that not wanting to come, you won’t come,” she explains. “You’ll say f*** it and forget about everything.”

What’s different about 1199C’s tutoring program, Williams says, is Hazelton.

The battle against hopelessness

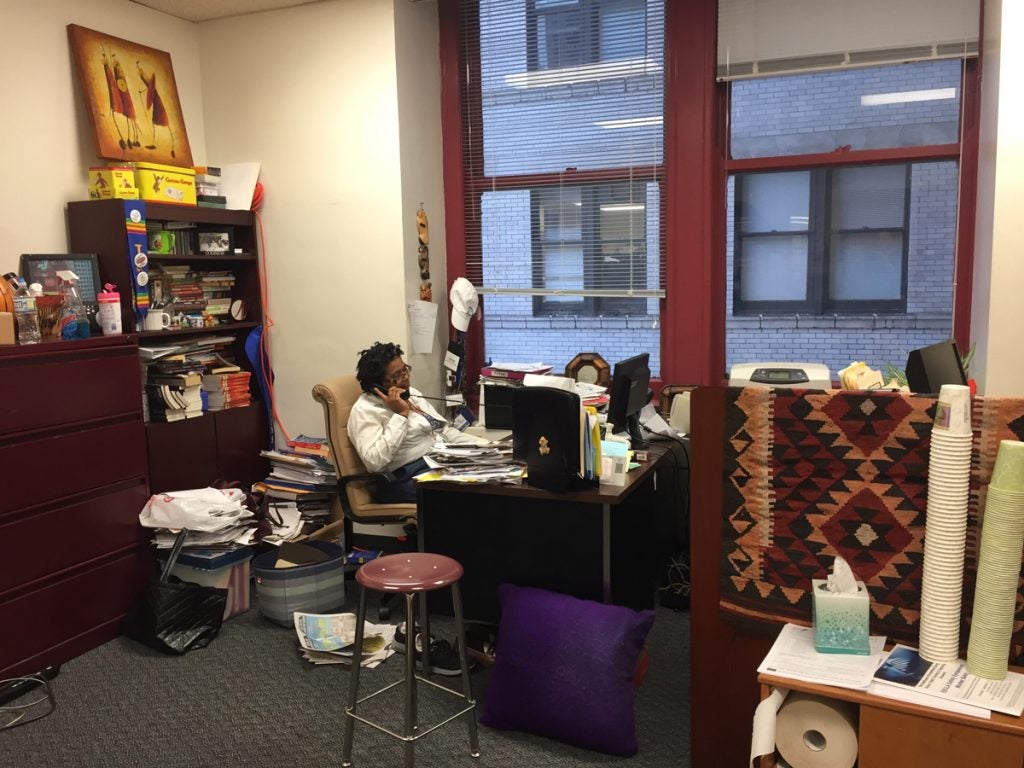

None of this operates without Lynette Hazelton. She gently cajoles people like Sandie Knuth into volunteering. She keeps personal tabs on seemingly every student. She is the embodiment of calm persuasion, with a personal warmth that permeates the entire adult education program at 1199C. And her voice — slow, soft, and sugary — perfectly matches her disposition.

Hazelton, raised in the Strawberry Mansion section of North Philadelphia, searches out small victories. Throughout the semester, she’s been bugging Christopher Johnson’s mother to get him involved in volunteering. Johnson may never hold a high-skill job, but he can still have a fulfilling life. If her involvement moves him closer to that goal, it’s a win.

Hazelton has no delusions about this work. She understands how far the students are from a GED, much less the middle class. But what’s the alternative? Giving up? Hazelton shudders at the thought.

“Shouldn’t you have a place where you can feel hopeful,” she asks. “Where you might be able to make it?”

This question, more than anything, seems to animate Hazelton, Knuth, and everyone involved in 1199C’s tutoring classes. They understand there may be no way to measure the effectiveness of what they’re doing. They understand it may have little effect at all. But they’re driven by the idea that something like this should at least exist for people who’ve already been passed over.

“What you don’t see is us allowing hopelessness to infiltrate,” Hazelton says. “There’s enough of that outside these walls.”

For all her virtues, Hazelton is still a one-woman crew in an operation that probably requires more. At times, it shows.

Midway through the course she tells Knuth that this course is only eight weeks long, not 10 weeks as originally suggested. It’s the sort of oversight that would seem absurd in any other school context, but here it’s met with chuckles and shrugs.

At one point, Knuth informs the students that class will only last eight weeks. No one seems surprised.

Reasons to run away

For the last class, in early June, Knuth lines up a slew of assignments and surprises.

Each student is supposed to take a final test, turn in paragraphs they’ve been writing throughout the semester, and give a presentation on some topic they researched independently.

About a half hour after class was supposed to start, only Christopher Johnson and a new student named Joel Newton have arrived.

Hazelton pops in and asks Knuth where everyone is. Knuth doesn’t know. She tells Hazelton about all of the culminating activities they were supposed to run through today. Hazelton laughs.

“Oh, so you gave people three reasons to run away,” she says.

In basic adult education, there’s a delicate balance between cheap success and the kind of daunting expectations that cause people to bail. Perhaps Knuth has asked for too much.

“If no one else shows up today, I’m going to cry,” she tells Hazelton. “I’m seriously going to cry.”

She and Jenni Jones wait, but no one else shows. And Knuth doesn’t cry. She grins and carries on.

Knuth and Jones crafted personalized certificates for each of the students, but they can only hand out two of them. Christopher Johnson gets the “repetition” award for the 102 paragraphs he completed over eight weeks.

Johnson flashes a shy smile. A standardized test taken after the class ends will reveal that he reads at about the same level he did when the class began. But he has changed. He appears more comfortable than when he started, even revealing a dry wit that catches Knuth by surprise. When asked a question now, he usually responds — often immediately.

Since he always arrived early, Johnson typically spent the first few minutes of each class listening to pop music blasted through a pair of taped-together headphones. During the final session — with nothing much else to do — he takes out his iPod mini and turns on the song “See You Again,” by Whiz Khalifa.

Knuth hears it leaching through the headphones and starts singing. Johnson looks over at her.

“You sing and I’ll rap,” he says.

Soon they’re huddled together, belting the chorus in unison:

“We’ve come a long way from where we began. And I’ll tell you all about it when I see again.”

It sounds cheesy. But in the moment, it looked like progress.

Progress and stagnation

After the course ends, most of the students take a standardized assessment called the TABE or Test of Adult Basic Education. The results reveal some surprising progress and some frustrating stagnation.

Thanks to Knuth’s class and a math class she’s been taking at 1199C, Katrina Williams’ scores improved across the board. She’s now doing math at a fifth-grade level and reading at a third-grade level, up from just below a second-grade level. Christopher Johnson’s reading score nudges ever so slightly upward. He’s now reading at just above a second-grade reading level.

Hazelton decides to advance both of them to the Level 1 course, anyway. There’s no firm criteria for this decision, but Hazelton believes they’ve earned a shot. They’ll soon be in a larger class with firmer expectations. The goal now is real, tangible progress — not simply good habits.

There’s precious little research on the effectiveness of basic adult education, which researchers attribute to the fact that there’s precious little funding available to academics who study the topic.

One researcher looked at adults in Portland, Oregon, who didn’t have a high school diploma, and found that those who attended at least 100 hours of adult education classes eventually made more money than those who didn’t. But it took years for those effects to bear out, and even the investigator, Stephen Reder, admits that it’s difficult to totally control for selection bias in the samples.

There is at least hope, though, that what the students did in Knuth’s class will someday improve their lives.

Anna-Gaye Johnson never took her follow-up exam. And she never came back to class. Instead, she found a job cleaning hotel rooms at a Marriott. She moved out of her brother’s house and got her own apartment — step one in the long journey to bring her children to the United States.

Maybe, in some immeasurable way, the structure and support she found in Sandie Knuth’s class nudged her toward the job market. But it’d be tough to tell.

The day before we were supposed to meet for a final follow-up interview, Johnson’s cell phone stopped accepting calls. She’s evaporated back into the working world, her education interrupted yet again.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.