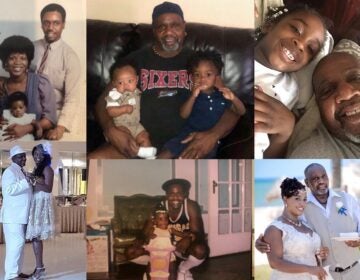

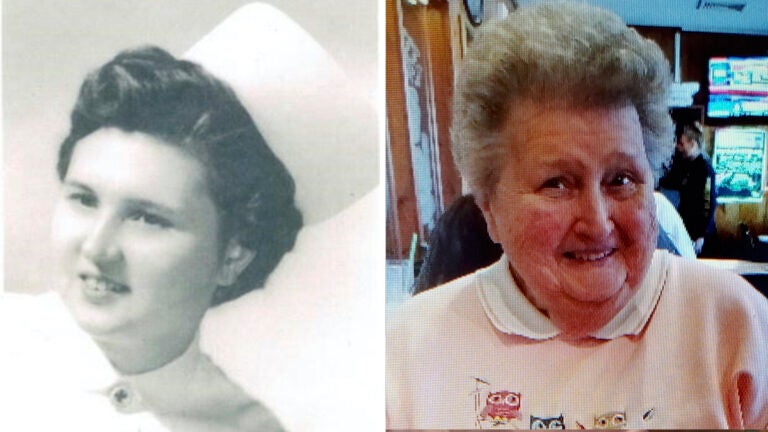

‘Big Momma’ Frances Pilot, 81, pursued a nursing career and family. And she did it her way.

Defying expectations for women, the Jersey Shore native raised kids while pursuing nursing, served as a volunteer before she was buried with an Elvis purse.

Listen 3:36

Frances Pilot graduated fromt the Ann May School of Nursing at Fitkin Hospital in 1959.

This story is part of WHYY’s series “COVID-19: Remembering lives we’ve lost” about the everyday people the Philadelphia region has lost to the coronavirus pandemic, the lives they lived, and what they meant to their families, friends and communities.

Two of Frances Pilot’s favorite songs were Gloria Gaynor’s “I Will Survive” and Elvis Presley’s version of “(I Did It) My Way” — apt choices for the 81-year-old matriarch who did both, despite coming of age at a time when women weren’t expected to do either on their own.

“Back then, even though it was breaking out of the ’50s and the ’60s, it was still considered that women should be staying at home and taking care of their family,” said friend Martina Singer. “[Frances] did that, but she also wanted to have her own independence and to show that you can be a mother, you can be a wife, you can be a friend, and you can be successful.”

Frances, a Jersey Shore native also known as “Big Momma,” died April 9 from complications of COVID-19, having lived to the beat of her own drum (and her favorite singer, Elvis) until the very end. Frances was one of nearly 100,000 Americans who have died from the virus featured on the front page of the New York Times on Memorial Day.

The front page of The New York Times for May 24, 2020 pic.twitter.com/d14JhFp4CP

— The New York Times (@nytimes) May 24, 2020

Born in Monmouth County, New Jersey, on July 14, 1938, to a farmer and factory worker, Frances was the first person in her family to go to college.

Those that knew her say it’s likely Frances’ humble beginnings influenced much of her drive. From a young age, she advocated for her right to a good education.

When Frances realized her learning environment wasn’t challenging her enough, she petitioned her parents to place her in a Catholic school. Frances was in middle school at the time, according to her younger sister Barbara Magda, but she already had nursing school in her sights.

“It was her dream,” said Barbara. “From the time she was little, as far as I can remember, nursing was the one thing she really, really wanted to do because of the fact she wanted to help people. She was very, very dedicated.”

Frances graduated from the Ann May School of Nursing at Fitkin Hospital, also in Monmouth County, in 1959. The following year, at the age of 22, she married Eugene Pilot.

She gave birth to three children in that marriage, and she poured everything into being a mother, according to her sister and children.

Kathleen Pilot, Frances’ youngest, remembers her mom would spend hours, day after day, helping her with schoolwork. When Kathleen was diagnosed with dyslexia, Frances bought her “Hooked on Phonics” and doubled down on helping her with work.

Kathleen said Frances was strict, but her love was never in question. Frances called Kathleen her “baby” until her final days.

‘I don’t need a man to validate me’

Though Frances was an involved parent, her independence and efforts to advance her career at Jersey Shore Medical Center — earning certification after certification until she became a psychiatric nurse — strained the marriage, according to Martina and Kathleen.

“[Frances] wanted to show [Eugene] that she can be just as powerful as he can and she can bring in money as well,” explained Martina, “and basically for him to think of her as an equal and not as somebody who is subservient or beneath him.”

Frances and her husband separated in 1974, only to reunite three years later. In 1985, the couple separated one final time. They divorced in 1987.

However, the love between the two remained. Kathleen said Frances and Eugene would always come together whenever there was a problem with the children. But after the divorce, Frances never dated again.

“My mother always said, ‘I don’t need a man to validate me for anything, Kathleen,’” her youngest daughter remembered. “My mother always said till the day she died that my father was the only man she ever loved and she didn’t want to ever, ever be in a relationship or get married ever again.”

Instead, Frances continued to nurture her other love: nursing. In many ways, the best was still to come for Big Momma’s career.

‘You’re supposed to be in school’

After working at the now-shuttered Marlboro State Psychiatric Hospital and Arthur Brisbane Adolescent Psychiatric Unit, Frances spent the final eight years of her career helping teen mothers finish their education.

The job was perfect for Frances, who loved children and inspiring women.

As the school nurse at the Department of Children and Families Regional School-Monmouth Campus, Frances cared for the children of teen moms while they worked toward their high school degrees.

“[Frances] would not allow them to miss school,” said Martina. “She would call them up, ‘Where are you? You’re supposed to be in school.’ And she would send the bus and go and get them.”

Martina remembers Frances also made the young families breakfast, and told the mothers to seize the opportunity they were being offered. Frances believed they could graduate and work around any personal issues or difficult situations if she offered them enough support.

It was the same advice and encouragement she gave her own children.

“My mother always said, ‘Get a great education, have your own money, don’t rely on anybody for anything, and just have a great career,’” Kathleen remembered.

Frances walked the walk, even after she retired in 2012.

‘Get up and go’

Always the loving grandmother, Frances continued to spend time with Kathleen’s daughter Amanda, who grew up having a special place in her grandmother’s heart.

Frances would often take Amanda, who has special needs, for the weekend to help give Kathleen a break from her corporate job. Amanda remembered whole afternoons with Frances spent playing card games, such as 500 Rummy, or drawing. Frances liked to sketch houses.

When Amanda was about 8 years old, Frances recommended that the little girl get involved in the Special Olympics in New Jersey. The move sparked more than a decade of volunteering with the organization.

Frances drove Amanda to swim and bowling practice, and helped other children in the Special Olympics program get ready and drove them to competitions. Frances was still going to events this year before the pandemic reached the region.

“She was very social, very loving, and always loved to get up and go and try new things,” said Amanda, now 20, remembering how Frances went on all the rides with her during their 2007 trip to Walt Disney World in Florida.

In addition to her work with the Special Olympics, Frances, a devout Catholic and former catechism teacher, was a frequent donor to her church’s food pantry. Those who knew her say she was hard to pin down before 6 p.m.

“She was out of the house all the time,” said Kathleen, “whether it be going to her doctor’s appointments or taking somebody to the doctor, taking somebody here, there, everywhere, taking somebody to church.”

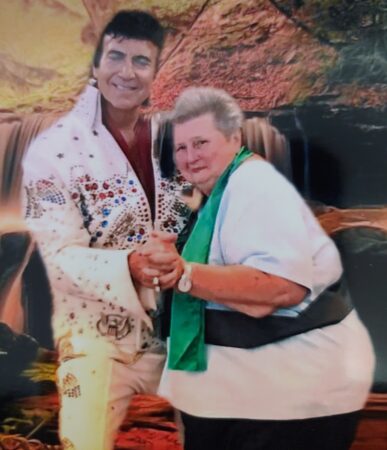

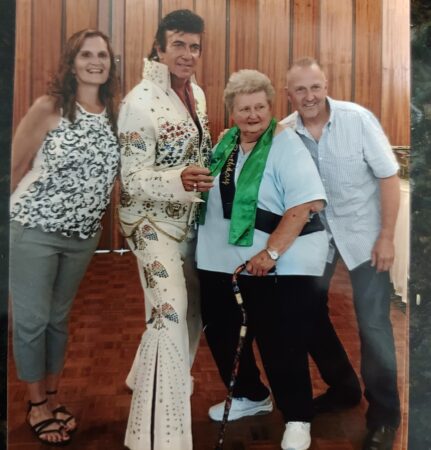

When she wasn’t volunteering, Frances loved shopping at Dollar Tree, feeding the deer that would visit her backyard, and listening to “The King” of rock-and-roll — Frances’ 80th birthday was Elvis-themed.

Frances also treated herself to a weekly trip to the same hairdresser for 40 years. Her style remained the same the whole time: short and in tight curls. It’s a style her family dubbed “the poodle do,” which, in her usual manner, Frances shrugged off.

“[Frances’] daughter would say, ‘Oh, my God, look at that poodle do,’” said Martina. “And [Frances] would just tell her, ‘Mind your own business. It’s not your hair. It’s my hair, and I like it.’ And that was that.”

Always the planner, Frances made her funeral arrangements long before the pandemic hit. Big Momma, who got her nickname because of her size, was cremated and then buried with an Elvis pocketbook.

And that was that.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.