Being black in Philly — like being black anywhere else

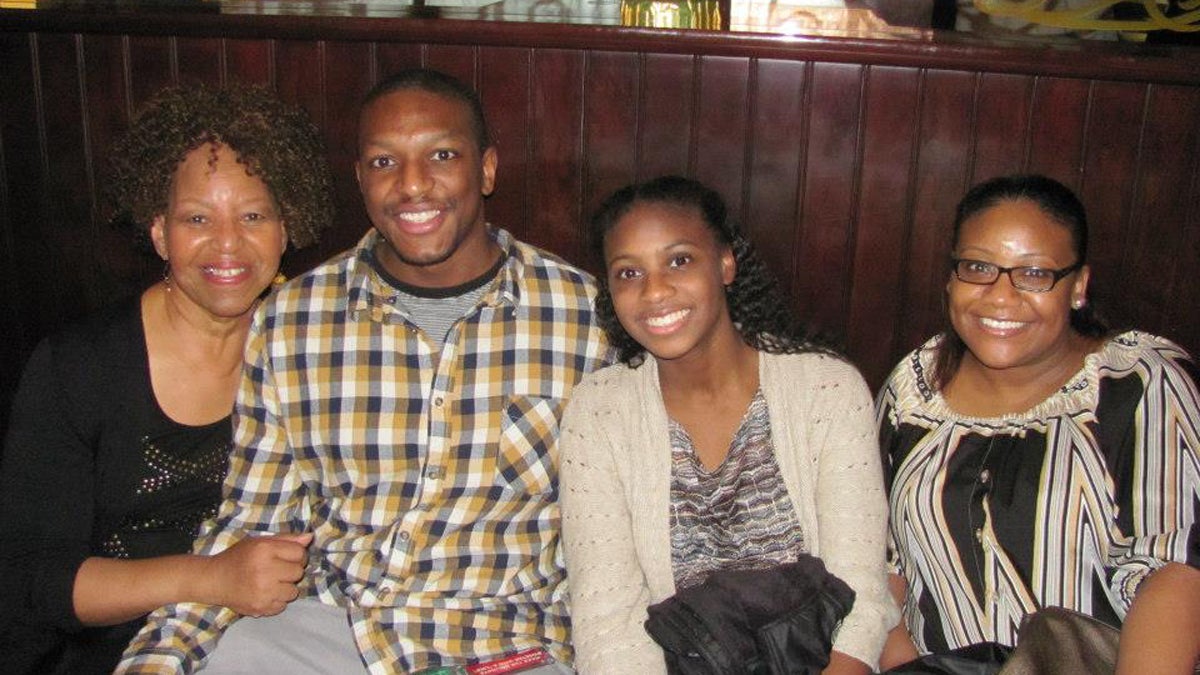

The author, Reginald Hall Jr., is pictured with (from left) grandmother Gwen Smith, niece Tiara Canty, and aunt Nina Rolle. (Image courtesy of Reginald Hall Jr.)

I suppose being young and black in Philly, I experience tremendous beauty mixed with ugliness. I consciously choose to seek out the beautiful parts here, do what I can to remove the ugly parts, and keep it moving when things happen outside of my control.

This is part of a series of essays about what it’s like to be you in Philadelphia. In an attempt to discuss issues of race and ethnicity respectfully and productively, all readers are invited to submit an essay to speakeasy@newsworks.org to contribute to the series.

—

As a young black man, I’m expected to behave, dress, and speak in certain ways. I’m expected to use slang. I’m expected to root for the Sixers and not care about the Flyers. I’m not expected to push myself academically. For some, my choices, style, and interests make me not black enough. For others, I’m too black.

How do I know this? Because I’ve been told to my face I’m “acting white” when I talk about the great time I had at a Flyers game. I’ve been told I “talk white” because of how I speak.

I recently went to dinner with my mom and three friends of hers who I met for the first time. The next day my mom told me how they gushed about how “well spoken” I am. That’s a back-handed compliment rarely said to a white man. My question is: How was I expected to speak? It’s not as if I talk like a university professor.

About 10 years ago, I was working in a bakery in Chestnut Hill. An elderly man came to the counter and started speaking in French. The owner suddenly cut the customer off, saying I wouldn’t understand him. I responded with “Hi, how are you” in my broken, high-school-level French. There wasn’t an expectation that a black kid knew another language.

These experiences aren’t frequent, but they’re not uncommon in my experience — and they’ve come from blacks and whites and people of other ethnicities. Strangely I’m okay with this — probably because I know their judgment has nothing to do with me, and I love who I am.

Some time last year, I walked up Chestnut Street with a buddy at night after a Phillies game. A car sped ahead to our left. Two twenty-something white guys were in the car. The passenger window slid down as their car idled at a red light.

“Get a f—ing job!,” the passenger shouted at me. The two laughed hysterically.

Racially motivated? I can’t be certain. But I do know the passenger looked me directly in the eyes and not my white friend.

It’s like what Dave Chappelle asks in his “Killing Them’ Softly” stand-up classic: “Ever had something happen that was so racist you didn’t even get mad?” That’s how I felt.

While my 6’3″ frame and dark brown skin can sure as hell clear a path at night or make old women fearfully cross the street, fortunately my experience being black in Philly is mostly positive.

Is that because I consciously seek out diversity in my work environments, my friendships and the places I hang out? I’m unsure.

Race doesn’t explain it all

I do recognize that my black experience in Philly would be different — not better or worse, just different — if I was in the lower class instead of the middle class. Excluding the significance of class in these issues of race is often a mistake.

I’ve been to many different sections in the city. I see people of various ethnicities often share more common experience than people who are of the same ethnicity but vastly different economic backgrounds.

My own family is an illustrative microcosm. One part of my family lives in a poor section in the heart of North Philadelphia. One cousin, M—, was born and raised there. She has traveled outside the city only once, for a wedding in California. She earned a high school diploma. She has stated that she plans to stay in Philly. Another part of my family lives in East Oak Lane. One cousin, A—, lives in a large, solid stone house. She’s traveled extensively to Europe and Africa and throughout America. She attended a private college and later earned a master’s degree.

One lifestyle isn’t better than the other, because both of my cousins are comfortable with their lives. But it’s clear to me how, although they’re both black and come from the same family, their interests and perspective of Philly are vastly different.

A mix of experience

Living in Philly, I know firsthand that acceptance of diversity is here if one seeks it out. Philly can also be extremely segregated, both racially and economically.

On a recent Wednesday night, I went to a housewarming/Flag Day party. (Yes, a Flag Day party!) The hosts were a white man and an Asian woman. In the kitchen I talked with a black man, a white man, and a Hispanic woman. People were laughing. Strangers became friends. Experiencing this atmosphere in Philly isn’t unusual for me.

So I suppose being young and black in Philly, I experience tremendous beauty mixed with ugliness. I consciously choose to seek out the beautiful parts here, do what I can to remove the ugly parts, and keep it moving when things happen outside of my control.

That perspective can be challenged when people assume I’m uneducated, or when racist incidents happen, but overall the good outweighs the bad for me as a black man in Philly.

—

Reginald Hall is a 26-year-old living in Center City. He helps ambitious people 18-35 find fulfillment and live better at www.freshwisdomonline.com.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.