aTAcK addiction offers three ideas to end overdose deaths in Delaware

With the opioid epidemic showing no signs of slowing in Delaware, advocates are calling on state lawmakers to stop talking and start investing in more treatment options.

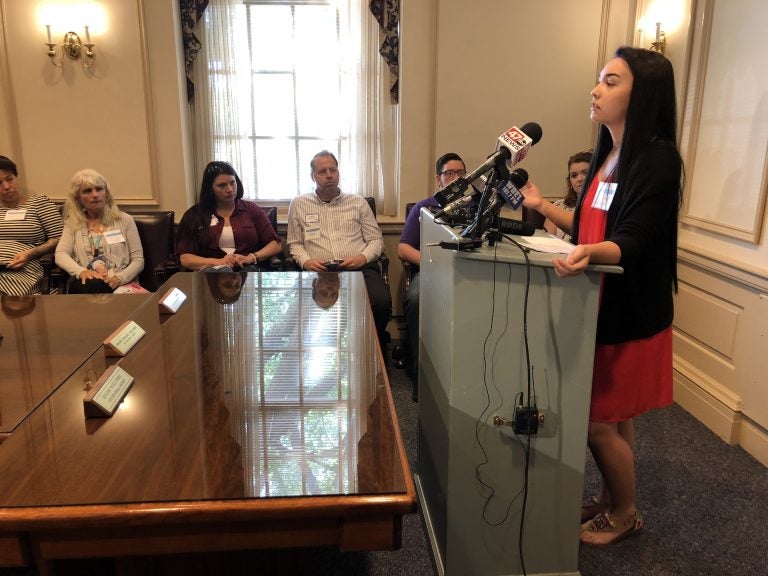

Emily Polecaro, 18, calls for a public recovery high school in Delaware at Legislative Hall in Dover Tuesday. (Shirley Min/WHYY)

With the opioid epidemic showing no signs of slowing in Delaware, advocates are calling on state lawmakers to stop talking and start investing in more treatment options.

At a news conference at Legislative Hall in Dover Tuesday, members of the advocacy group aTAcK addiction presented three initiatives they believe will stem the tide of the opioid crisis in the First State.

The news conference comes as Delaware public health officials reported 47 overdoses over the weekend, seven of them fatal. So far this year, 87 people have died from overdoses in the state.

“Our goal here today is to bring attention to three, important, high-priority measures we believe are necessary in fighting this problem. One, a recovery high school; two, a stewardship fund; and three, additional treatment and support options,” said Don Keister, founding member of aTAcK addiction. His son Tyler died from an overdose in December 2012.

“Later today, we will be visiting our legislators to answer questions and garner support.”

Public recovery high school

Emily Polecaro’s heroin addiction has taken her to various rehab facilities all over the country. Now sober, the 18-year-old is pushing for a public recovery high school in Delaware.

“You can’t send the kid to detox for seven days, get them off the heavy stuff, and send them right back to where they were getting their drugs. Expecting them to stay sober is not only unrealistic, it’s foolish,” said Polecaro, who speaks from experience.

Polecaro started using drugs in middle school. Over the next four years, she graduated to opioids and then heroin, toggling between addiction, treatment, relapse and treatment again.

“In treatment centers, they stress the importance of the avoidance of people, places and things, and then kids are forced to be sent right back to where you can get alcohol and drugs easier than you can on the street.”

Emergency room nurse Jen Sliney and husband, Ken, discovered their 16-year-old son was addicted to opioids in June. She said they spent more than $65,000 on an adolescent inpatient rehab facility and a sober living home in Pennsylvania.

“When Jeffrey completed his treatment in early November, we put as many support pieces into place so that he could continue his recovery here at home. Jeffrey has a psychiatrist, an addiction counselor and attends AA meetings regularly.

“What he didn’t have, was a safe place to come back to for school,” Sliney said. “My son is the kid who needs this school. He is the reality of this opioid epidemic, and he is not alone. We need a common place for families like mine, daughters and sons like mine, a school with peers for them to come together and support each other through recovery.”

“There is not a family in the state of Delaware that has not been affected by some type of addiction. Why we are procrastinating on this issue, I have no idea. It’s almost like having a person in the middle of the street bleeding to death and we’re not willing to go help,” said Merv Daugherty, superintendent of Red Clay Consolidated School District. “We have over 140,000 students in the state of Delaware. If we go by the national statistics, we have between 700 and 1,000 young men and women who are suffering from some type of addiction.”

“One of the hardest truths to accept is that sobriety is more important than education,” Sliney said. “Traditional high schools are not equipped to meet the unique needs of adolescents struggling with substance abuse. Returning to the same location, previous use, only puts students at a higher risk for relapse.”

Board members of aTAcK addiction are asking lawmakers for $2 million to get the recovery high school up and running and operational for at least four years.

Treatment and recovery support

The opioid public health epidemic hit the state when Rita Landgraf served as secretary of the Department of Health and Social Services. She also sits on the nonprofit’s advisory board.

“The time is now that, economically, our state is in a much healthier position that we need to invest in treatment and recovery options. We need every tool in our toolbox to actually deal with the disease of addiction,” said Landgraf, who was adamant that families should not have to leave the state to seek treatment.

“As a public health official, we actually do know how to prevent this disease, we do know how to intervene when this disease occurs and what we need is the availability of treatment, sober living beds, more inpatient treatment centers, so we do not have to send our children, our loved ones, our colleagues out of state in order to get well,” she said. “Any other disease, we are able to support here in our state, except for this one.”

Landgraf said she’ll ask for $4 million from the state to expand the availability of these options.

In total, board members are seeking $6 million — to be carved out of a projected $101 million budget surplus over the next years — to fund their priorities.

Stewardship fund

Dave Humes, public policy coordinator for aTAcK addiction, has been working with state lawmakers since 2015 to establish a stewardship fund through legislation. Two bills have been introduced thus far, House Bill 358 and Senate Bill 176, to establish the fund. Both measures impose fees on the sale of opioids in the state. HB 358 also calls for any settlement money resulting from lawsuits related to opioids be diverted into the fund. The stewardship fund would then support opioid addiction treatment options in Delaware.

Attorney General Matt Denn filed a lawsuit in Delaware Superior Court accusing Purdue Pharma and Endo Pharmaceuticals of misrepresenting the addictive nature of their opioid painkillers. Purdue markets oxycodone under the brand name OxyContin, and Endo markets the same drug under the brand name Percocet. The suit was also filed against retail pharmacies CVS and Walgreens.

“Our state estimates the cost to the citizens to be over $100 million per year. These costs are incurred by hospital and health care systems, by our EMTs and police, by our first responders, by our Medicaid system, by our social services and by our criminal justice system,” Humes said. “Now is the time for Delaware to react in a bipartisan fashion by enacting ‘Stewardship Fund’ legislation in order to stem the death of its citizens and provide expanded treatment for those with the disease of substance use disorder.”

Humes is pushing for both pieces of legislation to be passed during this session of the General Assembly.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.