Am I a stranger to my brother?

It’s the responsibility of people like me to keep looking for people like him to make those chance encounters more than just shouting matches on the street.

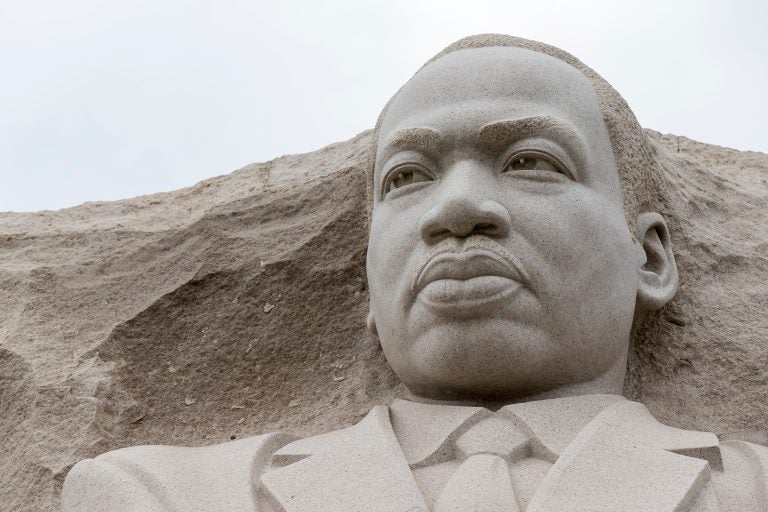

The Martin Luther King Jr. National Memorial in Washington, D.C., honors King's national and international contributions and vision. (actionsports/Big Stock Photo)

In observation of the life and death and legacy of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., NewCORE and Gwynedd Mercy University are presenting “Examining ‘Post-Racial’ America” on Feb. 28, a public discussion that will explore the feasibility of a post-racial society and the role civil discourse will play in achieving that ideal. WHYY is publishing a series of essays on that theme.

—

The encounter on the street took all of 12 seconds.

I was walking up the block when I encountered a group of young, African-American teenagers simply hanging in front of a store.

As I passed by, one of the young brothers called out to me.

“What’s happenin’ Old G?”

“All good,” I replied.

“What’s your name, bruh?”

In fairness, I was rushing to get somewhere, and, being from the streets myself, I know that asking for your name or the time of day is one of the oldest tricks in the books for slowing somebody down to ask for money or any number of city hustles.

So I didn’t answer and kept it moving.

My non-response prompted his response.

“F*ck you, then.”

I should have kept going, but here was a young brother — the kind of brother who I spend most of my waking days and nights as a professor, pastor, uncle, mentor working with — who just dismissed me with an expletive.

So I stopped.

“I’m sorry. What did you say?”

“I said, ‘F*ck you.’”

What I didn’t realize was that, by stopping, I was challenging him in a way that I didn’t intend.

One of the sisters standing with him asked him to ease up a bit. He didn’t.

“You better step off before you get got.”

“Brother,” I said. “I was just trying to understand what you said.”

“Sir,” the sister interjected, “just f*cking go.”

So I walked away. And I heard the young brother’s anger as he shouted down after me. I kept walking as he threatened (probably more to his crowd than to me) to follow me down the street and kick my ass. I kept walking as I wondered how and why such a chance encounter could so quickly and easily escalate to violence.

When I got to my car, I had so many mixed emotions that I sat there not knowing what to do. On the one hand, I was pissed because this black-on-black violence angers me every time it rears its ugly head. On the other hand, I was relieved because — as a 55-year-old black man — my street fighting skills left me a long time ago. But mostly, I was confused because I couldn’t understand why it happened at all.

Finding the answer to a lion’s roar

Was it just a little bit of street bravado?

Was it because he was just an angry young brother looking to pop somebody?

Was it because my actions had unintentionally been misinterpreted as an aggressive move whose only response would be one of violence?

Maybe it was a combination of all of these. Or maybe it was a combination of none of these.

But the bottom line is that, regardless of the reason, it hurt my heart that all this young brother saw was somebody who deserved a beat down — simply because we were briefly sharing the same space. He couldn’t know that I was a caring father, a pastor of a congregation, an employer within the community, a professor committed to education.

He didn’t know, and he didn’t care, which is why what happened next was so profound.

I went back to find this young brother and his crew, but they weren’t there. I drove around looking for him, but I couldn’t find him anywhere.

I’m not sure what I would have done if I had found him — or even how he might have interpreted my attempts to locate him. But the reality is, there are thousands of young lions just like that on every street corner in every community. And, as long as they are out there, it’s the responsibility of people like me to keep looking for people like him to make those chance encounters more than just shouting matches on the street. Instead, it may just lead to a dialogue that can shape us both for a lifetime.

I do a lot of work in the community. I’m honored to be one of the founding members of an inter-faith group called NewCORE (which stands for the New Conversation On Race and Ethnicity) that gathers every month to have conversations about the racial problems that often tear people apart. Ten years ago, I created the Bridge Walk for Peace which attracts folks from every corner of the region for a sunrise walk across the Ben Franklin Bridge on the morning of April 4 to commemorate the assassination of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King as a way of recommitting ourselves to the kind of peace that King lived, fought, and died for.

And now, I’m proud to have participated in the effort to have 80 conversations in 80 days (acknowledging the time from when King celebrated his birth on Jan. 15 to his untimely death 80 days later) around issues that continue to shape King’s legacy.

Throughout his life, King was a master of mobilizing people from disparate backgrounds and communities in building coalitions that would eventually move mountains. At the time, however, the issues around civil rights were far more stark than they are today.

- Breaking down the physical and legislative barriers of segregation.

- Marching for equal rights and respect for our humanity.

- Fighting for a future, as King said, in which content of character outweighs complexion of skin.

And we’re still fighting on battlefields on which the terrain may have shifted, but the prize remains the same: dignity as equals sharing common ground. Whether we come from the same tribe, though originate from different sides of the tracks, we owe it to each other to build from that which binds us, rather than giving voice to that which keeps us apart.

—

David W. Brown is one of the founding members of NewCORE. He is the assistant professor of instruction at Temple University’s Klein College of Media and Communication.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.