A child psychiatrist shortage fuels a crisis and workarounds

Listen Illustration by Steve Teare) " title="pulse-psychiatry" width="1" height="1"/>

Illustration by Steve Teare) " title="pulse-psychiatry" width="1" height="1"/>

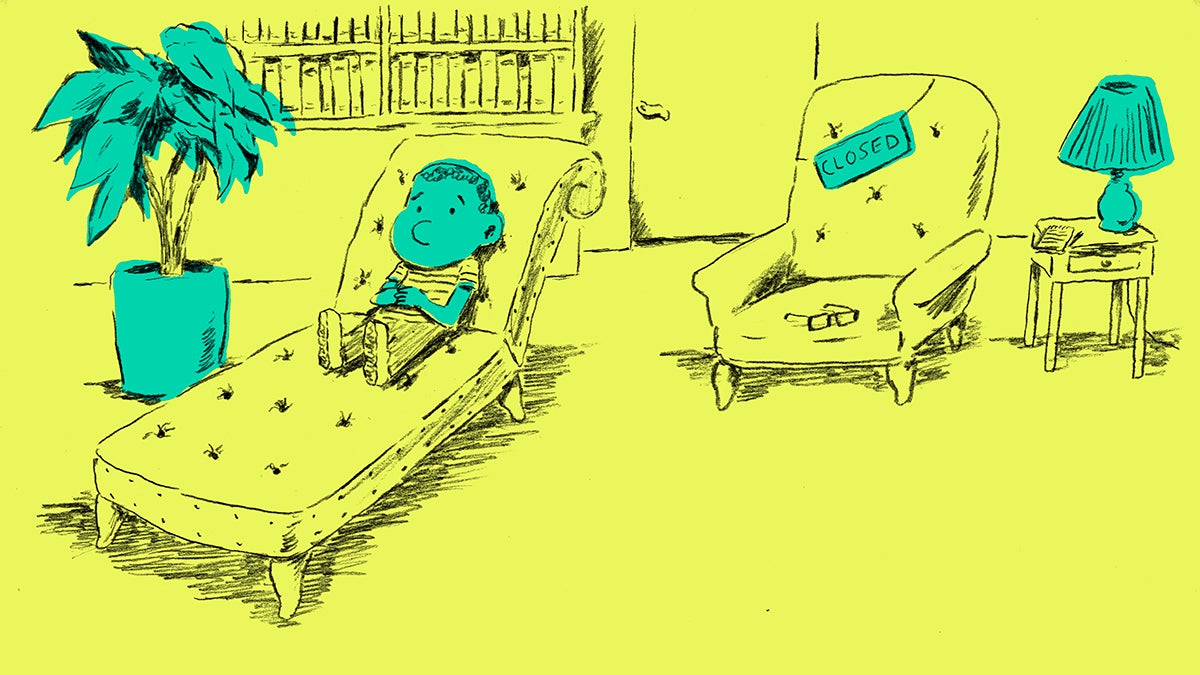

In the U.S., not one state has a sufficient number of child psychiatrists, according to the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatrists. (Illustration by Steve Teare)

As Dr. Andi Fu walks through the psychiatric wing of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, a lanyard dangles around her neck that often makes her teen patients chuckle: it has Dr. Harley Quinn, the infamous partner to that all time villain The Joker, printed all over it.

“She’s like the most famous psychiatrist that kids know,” Fu said, adding that it sometimes becomes a fun inside joke. “Their parents have no idea who it is.”

Joking aside, in many ways, that badge reflects Fu’s own roots for getting into this field.

“I think part of my motivation to go into child psychiatry is I was such a weird kid,” Fu said. “I was like comic book reading, anime drawing weird.”

Fu just completed her residency training in child psychiatry at CHOP. She is part of a new generation of child and adolescent psychiatrists. It’s a small one entering a strained workforce. Still, choosing this speciality was a no-brainer for Fu. The “wonder years” are a vulnerable, critical time she says.

“I’m surprised anyone survives,” Fu said. “When you think back on ages 0 to 18, that’s an immense amount of stuff that’s happening that’s kind of traumatic and trying for almost everyone in every walk of life. And I think putting yourself in the position to help kids through that, and put them in the best possible place so they can live the life they want to live and be happy, I think that’s a great thing to spend my time doing. And I hope that other people would too.”

A lot of other people, though, don’t want to do that. In the U.S., not one state has a sufficient number of child psychiatrists, according to the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatrists. Many worry this shortage of mental health specialists, and child psychiatrists in particular, has created a crisis in real time and another one in the making.

Dr. Andi Fu just completed her training in pediatric psychiatry at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. (Elana Gordon/WHYY)

Dr. Andi Fu just completed her training in pediatric psychiatry at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. (Elana Gordon/WHYY)

The origins of the shortage

A couple of years ago, a group of Harvard doctors shined a spotlight on the crisis. They led an unusual experiment, posing as the parents of a 12-year-old child with depression. They called hundreds of child psychiatrists across several cities, to see how easy it would be to get an appointment. The results were troubling. Only a few psychiatrists had openings and for those that did, the average wait time was nearly a month and a half.

The stakes for getting care are high. Untreated, mental illnesses can have lifelong impacts on a child’s growth and development. Mental illness is involved in almost all child and adolescent suicides, which is the second leading cause of death for that age group, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

But the problems with mental health care in America aren’t new. Donna Shalala, Health and Human services secretary in the Bill Clinton administration, called it in a press conference almost 20 years ago.

“We believe it’s a public health crisis,” Shalala said.

She and the U.S. Surgeon General at the time, Dr. David Satcher, outlined that crisis in a groundbreaking report on mental health care. One in five young adults, the report highlighted, would go on to develop a mental health condition. But there was “a dearth” of child psychiatrists and other mental health specialists that were needed to intervene and treat kids with potentially debilitating conditions, from major depression to anxiety disorder to Attention Deficit Disorder.

The nation averaged about one child psychiatrist for every 11,000 kids.

A growing problem

And yet fast forward to today: “The situation then is distressingly similar to what it is now,” said Dr. Gregory Fritz, President of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

Fritz co-chaired a 2001 task force following that Surgeon General’s report.

“We had several major initiatives that we undertook,” said Fritz. “One was to incentivize medical students to go into child psychiatry.”

The field needed a makeover, recalled Fritz. But from the get-go, the odds were stacked against them. Training for child psychiatry is longer than other specialties, and the salaries are lower. So, spend more and then earn less is just a hard sell.

“To become a child psychiatrist, the fastest possible way to do it is in five years, and often it takes seven years,” Fritz said. “And meanwhile, the average medical student has somewhere between $150,000 and $220,000 dollars of medical student loans.”

The group proposed loan relief programs and fast-tracked trainings, but a lot of those efforts stalled in legislation.

Fast forward to today:

“All of our work hasn’t made much of a dent,” Fritz said.

Fritz is still banging his head against the wall to come up with solutions, all the while juggling his own backlogged practice.

“It feels terrible to tell somebody who’s in crisis that we can see your child in a month. Who wants to do that? That’s horrible,” he said.

This all sounds familiar to Dr. Tami Benton, Chief of Psychiatry back at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. She says these days, CHOP’s emergency room is frequently busy at night because the city’s one psychiatric crisis center for kids is often full and on diversion.

Families, she says, are under a lot of stress, and many are coming in for avoidable emergencies. Parents may have tried to get a psychiatrist appointment for their child months ago but couldn’t get in. As it stands, Pennsylvania has about 422 child psychiatrists for 2.7 million kids. Navigating insurance coverage is also tricky and fragmented.

Right now, Benton has 16 child psychiatrists in training at CHOP. Still, that’s not going to be anywhere near enough.

“The average age of a child psychiatrist is about 55, so the workforce is aging but the number of people coming in to replace them is not growing very rapidly,” Benton said.

First, she says there just aren’t enough slots to train the child psychiatrists that are needed. But even with that limited number “there’s more slots than there are people to fill them.”

She says medical students don’t get much exposure to child psychiatry. Plus, it’s just isn’t a popular specialty. It all means that pediatricians are having to fill a very big void.

Pediatricians caught on the frontline

On a recent afternoon, Dr. Steven Shapiro meets with a patient he has been seeing since she was born.

“Hello! It’s nice to see your smiley face for a change!” he greets her in the exam room. “You feel well?”

The patient responds with a “yeah” and smiles.

“Sleeping OK?” Shapiro asks.

“Better than I was, yes,” she says.

The patient is in high school now, but her life took a dark turn this winter. Around December, she became crippled by severe anxiety. She didn’t want to see friends or go out at all. She fell behind in school.

Here in this private practice, Shapiro sees mental health concerns surface a lot. He screens for it, too. Whether or not pediatricians are trained in mental health, they’re being forced to respond. At the same time the stigma of mental illness is decreasing and more patients are coming to them asking for help.

“The biggest challenge I have faced in my recent career has been to learn about how to deal with these emotional, social, and anxiety-related disorders,” said Shapiro. “There’s a lot of docs that haven’t learned about these things.”

Dr. Steven Shapiro has been a pediatrician in Montgomery County since 1980. Responding to mental health is a growing part of his practice. (Elana Gordon/WHYY)

And that can be a problem. Training to be a child psychiatrist takes a long time for a reason. This is a complicated field. Without that training, pediatricians are at a disadvantage when it comes to diagnosing and treating mental illnesses. That treatment can include powerful medicines on a child’s developing brain.

Shapiro says traditional pediatric training never included much about mental health. He has had to learn on his own about drugs and other treatments for basic mental health conditions, like depression and anxiety. On top of that, taking on mental health is time consuming. These are longer conversations.

“Here’s the reality. This visit costs me a lot of time: 15, 20, 25 minutes. I don’t get paid for this visit any more than I do for seeing a child with an earache,” Shapiro said. “As a matter of fact if I see more kids with earaches I’ll make more money than if I see this young adult and help to understand her situation. That’s the problem with behavioral health.”

And when kids have more complicated problems or multiple ones, which happens, pediatricians need help. Shapiro knows he has limitations in what he can do when it comes to co-morbidities or when a child isn’t responding to treatment in the way he might have expected. But that specialized help isn’t easy to find.

“The referral path is convoluted and complicated and based on individual relationships,” he said.

Finding workarounds

Shapiro is working with a group of pediatricians across the region on a different model of care that’s been gaining traction lately. The idea is to better integrate mental health services into pediatric practices. Shapiro hopes once their group launches, they’ll have a psychiatrist available within their network of pediatricians.

“If I could have someone here, that, to me, is the essence of what we need,” Shapiro said.

The Affordable Care Act paved the way for this approach with new reimbursement models.

More than two dozen states have also been experimenting with another way to help ease the pressure. It’s a virtual support system for pediatricians. When doctors hit a situation they can’t handle or are unsure about, they can dial up a number and get guidance from a child psychiatrist. It’s called TIPS in Pennsylvania. It’s specifically covered under Medicaid. Dr. Evelyn Reis, a pediatrician affiliated with the Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, loves it.

“Oh my heavens, I joke sometimes that I have TIPS on speed dial, but that’s not really a joke,” she said.

She calls for situations she doesn’t know how to manage, and when she and the families are in a bind.

“I think it feels good to take on additional care responsibilities and help families in ways I haven’t before,” Reis said. “But it is a little anxiety provoking for us as well.”

Pennsylvania jumped on board with the program a year ago, after a report found a high prevalence of doctors who were over-prescribing antipsychotic drugs to kids and teens on Medicaid, especially those in foster care. It found that half of kids on antipsychotics had conditions like ADHD, which don’t warrant such heavy medicines that can come with big side effects.

Reis says this system of virtual handholding gives her the support she needs to make good decisions and become more comfortable prescribing medicines that are new to her practice. In Pennsylvania, the TIPS program also connects patients with an immediate evaluation with a pediatric psychiatrist, a necessary first step in kickstarting a referral process.

Back to square one

Approaches like TIPS are offering backup to pediatricians on the frontline, but their success depends on actually finding a child psychiatrist to work with and that’s the big problem. Again, not enough medical residents are choosing child psychiatry.

“Yes, there’s a giant shortage that seems to be getting bigger,” said Dr. Andi Fu.

Fu, that Harley Quinn lanyard wearing child psychiatry graduate, is one of the few exceptions.

“Personally, I feel great,” she said. “I feel like I’m doing what I can to help out. Part of my career trajectory is probably going to include doing what I can to interact with medical students and get more of them to go into child psychiatry.”

Fu knows that the long training and the lower salary will be a deal-breaker for some, but she thinks it’s more than that. Early intervention in mental illness, like any disease, can make a real difference. But that mental health intervention is not always an easy fix. And doctors like to fix things.

“Whereas in psychiatry you have to be ok with, ‘I tried my best. I hope that worked.’ Half the time it’s not—half the time my patients don’t want anything to do with me. And that’s extremely uncomfortable, I think, for a lot of non-psychiatry physicians.”

She says she is well aware of the challenges of the field, of the shortages and the pressures she’s about to step into, but for her that’s all the more reason to jump right in: the success of future generations of young adults depends on it.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.