East Logan Historic District?

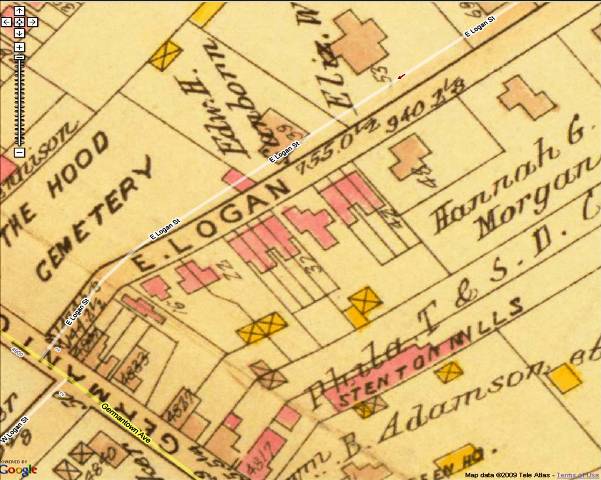

1910 Philadelphia Atlas by Bromley

July 6

By Alan Jaffe

For PlanPhilly

It all began with a call to the cops.

An attractive old house down the street from Sandra Lark was being divided into apartments by its owner, and that upset her. Lark and her family were newcomers to the East Logan Street neighborhood in Germantown, but a longtime resident and community activist told them that this was a historical street and Lark should alert authorities about the work down the block.

The first call didn’t work. The police said there was nothing they could do to halt the property owner’s renovations. Lark tried again, this time asking for a supervising officer to visit the site. It turned out the owner lacked the plumbing and electrical permits needed to continue the division of the structure. The reconstruction was stopped.

The next calls were to the Philadelphia Historical Commission and then the Preservation Alliance of Greater Philadelphia. Patrick Hauck, director of Neighborhood Preservation Programs at the Alliance, came out for a look at East Logan Street.

“Patrick noticed that all of these homes were built during certain periods. He said, ‘I think you have something here,’” Lark recalled.

What they have is one of the smaller applicants for a historical district in Philadelphia –just 26 parcels containing 30 structures, mostly single-family homes, carriage houses, and outbuildings dating from the 1700s to the mid-1900s, with many erected in the 1860s.

Hauck learned that much of the East Logan block between Stenton and Germantown Avenues was already on the National Register of Historic Places under the earlier name of Fisher’s Lane, and five buildings were listed on the Philadelphia Register. “So they were in a really good position. We realized this was a great opportunity to bring together people around the area and on the street,” Hauck said “The other great thing was, this was not something happening from without the neighborhood, but from within it.”

An application to designate the block of East Logan Street a local historic district, thereby protecting it from any unauthorized alterations, was submitted to the Historical Commission on May 15, and approval is expected by the fall. According to Hauck, “This is a really good model for how a small neighborhood can do this.”

Natural Leader

Lark, her husband Nathaniel, and their two children moved to Germantown from Port Richmond two years ago. “I’m just a housewife who got into history because I started home-schooling my kids,” she explained. Realizing there were few designated sites outside Center City to take her children to learn about American and Philadelphia history, Lark educated herself about the winter at Valley Forge, the Battle of Brandywine, and the rich story of Germantown. Mother and students visited the cemeteries in Germantown, identified the prominent figures buried there, and then found the houses they had lived in.

“The history of Philadelphia really connects to every race. I don’t know if people realize that,” Lark said. “You have black Americans, Spanish, Cuban, Caucasian and Asian people who contributed to our history. People need to understand we’re all in this together.”

It was natural that Lark would lead the effort to preserve the properties on East Logan Street. “The neighbors were very receptive to the idea of a historic district, but they didn’t know what to do,” she said. Some expressed concerns about the costs of historic restoration. “So I have to be an advocate and tell them places to go” to find affordable services and materials. This summer, neighborhood workshops will be held to encourage residents to find ways to repair their homes following preservation guidelines.

Besides the structures on either side of the block, Lark also hopes to protect a greenway that has grown up along a portion of Rockland Street behind the homes on her side of East Logan. “We want to maintain it as a green space. We noticed that we were getting all kinds of birds: cardinals, blue jays, even hummingbirds. So we want to keep that space. It’s also a great barrier to traffic on Stenton Avenue. And our neighbors on Stenton would also like to keep it; we have common agreement on that.”

Once the district has been approved, Lark hopes to attract the tourists who come to Philadelphia for the full story of the nation’s founding. “We just have to give them a purpose for coming here,” she said.

“We’d also like to have traveling art exhibits come through,” like the recent Hidden City tours. “We would like to have people open their homes and help develop an art bank for people to visit. We’d like to open our greenway in the back, and our yards can be an open door to this space.”

Living and Dead

East Logan Street was a frequently used thoroughfare, “a busy street by 17th and 18th century standards,” explained David Young, executive director of Cliveden, where the Battle of Germantown was waged, now a National Trust Historic Site. “That area of town changed a lot over the years. The two great constants of Germantown are continual change and a sense of independence from the rest of the city.”

A prominent landmark of East Logan Street is the Hood Cemetery, at the intersection with Germantown Avenue. Originally known as the Lower Burial Ground, it dates to a few years after the landing of William Penn. Early German and Dutch headstones can be found among its rows, which also include Revolutionary War soldiers who were killed in the Battle of Germantown, as well as casualties of the War of 1812, the Seminole, Mexican and Civil Wars.

The most famous occupant, according to local historian Gene Stackhouse, is Condy Raguet, founder of the Philadelphia Savings Fund Society (PSFS). Sgt. Charles S. Bringhurst, who climbed the rampart at Fort Sumter three times to replace the Union flag, also rests there.

About 1,200 people were buried in Hood, a majority of them infants, Young said. About 100 stones still stand. The earliest legible date is Oct. 18, 1707, marking the grave of Samuel Coulson, age 9 weeks.

The name of the cemetery was changed in 1847 in tribute to William Hood, who offered to erect the ornate marble gate and wall in exchange for a burial place near the entrance.

Early Suburb

In the mid-1800s, Germantown was changing from Colonial village into a summertime community, according to the Statement of Significance by the Preservation Alliance filed with East Logan’s application. The yellow fever epidemic of 1793 drove affluent families from downtown Philadelphia to the healthier air of Germantown, where they built elegant homes with fine gardens, in keeping with America’s first landscape architect, Andrew Jackson Downing. The arrival of the Germantown and Norristown Railroad also helped turn Germantown into a “garden suburb.”

East Logan Street’s forerunner, a route to nearby mills on Wingohocking Creek, appeared on a 1766 survey. It was named Fisher’s Lane in the 1770s, after Thomas Fisher, son-in-law of William Logan, who was the son of James Logan, an agent for William Penn and a leading political figure in Pennsylvania. Fisher built a stone home along the Wingohocking on the Logan estate called Stenton. The street name was changed to East Logan in the early 20th century.

Development began on the block on the north side, near Hood Cemetery. The first home dates to 1729 and the 18th century portion remains, though the house was enlarged in the 1870s and renovated in the 20th century.

The next house on the north side was built in the 1850s for T. Charlton Henry, an Italianate villa style that follows Downing’s principles, set back from the street. Departing from Downing’s brick and stucco preference, the house is built of local schist, with smaller stones mingled with larger. Henry was the son of Mayor Alexander Henry and served as president and founder of the Savings Fund for Germantown (now Germantown Savings Bank).

The prominent artist Joseph Pennell also lived on East Logan Street from 1870. While he lived there he painted an entry for his school art show, depicting “the ugly house across the street,” the home now owned by Sandra Lark.

In the 20th century, Germantown become more accessible and took on a more urban appearance, according to the Preservation Alliance description. Dense rowhouses appeared in lower Germantown. “With its spacious lots and large detached dwellings in contrast to the close rowhouses that surround it, this part of East Logan Street is significant today as an early suburban streetscape that has survived remarkably intact from the period of its highest development,” the Alliance statement explains.

“This was a little pocket that magically remained there,” Hauck said.

Contact the reporter at alanjaffe@mac.com

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.