Pier 11 concepts get initial airing

June 18

By Thomas J. Walsh

For PlanPhilly

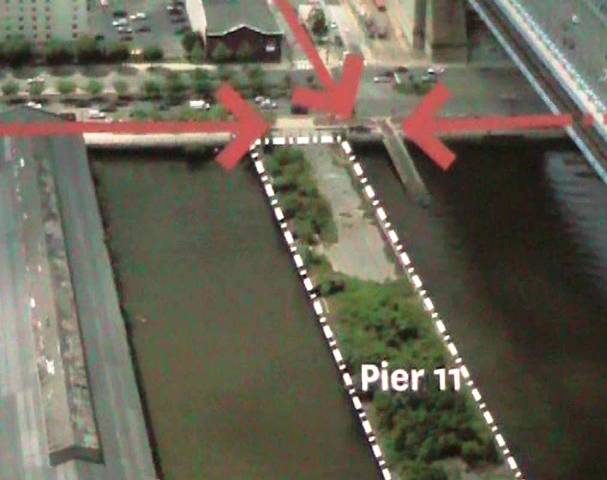

More than 200 people came to Columbus Boulevard’s Festival Pier on Wednesday night to hear about the approaches that four design teams would bring to a redeveloped Pier 11, at the foot of the Benjamin Franklin Bridge at Race Street.

The abandoned strip, an 80-foot by 540-foot “finger pier,” is tiny, but represents what could be the “real translation” and the “first, real, tangible” project to come to fruition under the PennPraxis-led Civic Vision for the Central Delaware, said Andy Altman, the outgoing deputy mayor of commerce and economic development.

The ideas ranged from very broad visions, based on past and current work, to quite detailed plans that would transform the pier into a public space that is part ecological preserve (employing solar and wind power), part environmental education center and – incorporating the city-owned Pier 9 just across the quay to the south – part art gallery.

The winning team will lead an effort by the Delaware River Waterfront Corp. that will cost between $3 million and $3.5 million, a combination of public money and funding from the William Penn Foundation.

“We will be back frequently to engage in these kinds of conversations,” said Marilyn Jordan Taylor, chair of the DRWC planning committee and dean of the Penn School of Design, who moderated the evening. “We’re just thankful and we look forward to nights like this when we can look prospectively forward, for how we bring the best ideas of design together with the public will to make this place truly great.”

The four design consultant finalists were recruited through a request-for-proposal to prepare an urban design plan for the intersection, which, along with Pier 11, includes Pier 9, with a large garage structure, as well as a former Philadelphia Water Department pump house across Delaware Avenue.

“One of the things I was struggling with throughout all the presentations was, what is Pier 11 meant to be?” said Alex Balloon, a Center City resident and historic preservation consultant. “Is it meant to be for recreation? Is it meant to inform and teach? That’s a strategic choice that I think the [DRWC] is going to have to make.”

The four finalists are: Andropogon; Field Operations; Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates; and W Architecture and Landscape Architecture. Of the four only Andropogon is based in Philadelphia. The others are headquartered in New York.

Coming prepared

Andropogon, which went first (according to alphabetical order, Taylor said), was by far the most detailed in its vision, calling for an “iconic EcoPierPark” design that would reflect through various uses the unique ecological context of the pier’s location, in the midst of the Delaware River estuary.

José Almiñana, principal at Andropogon, spoke for 17 minutes, fairly stunning the audience with an array of ecological opportunities that include harnessing power from the small piece of land via solar panels, new conical wind turbines with vertical axes, or water power generation to take advantage of the pier’s seven-foot tidal shifts – or all of the above. This renewal energy – to eventually have the park pay for itself – would be facilitated through a subcontractor, Natural Currents LLC, of New Bedford, Mass.

“What we’re suggesting to you here is that we fundamentally describe a paradigm shift in the way we relate to the river, and we honor the river,” Almiñana said. “That we take from the river, once again, and we make things better, and put them back into the river.”

This would include “ecological monitoring,” and could be a green jobs training site, as well as making it a place as central to the city as any of its most enduring parks, integrated into the surrounding neighborhoods.

Almiñana also described an “iconic canopy” over the pier that would extend all the way up Race Street, under Interstate 95, and into Old City – adding another layer to the mind’s eye for what the currently stubby, very dead pier could become, once resurrected.

“There is actually a layer of living systems that can be placed upon this pier,” Almiñana said. “But there is actually the capacity to connect the fabric of the city” as well. “Think about the potential” for an extension of First Fridays, he mentioned, or “Second Saturdays” for “Philadelphia MOE Art” within Pier 9 (the “Museum of Environmental” art). The pump house could have a pedestrian connection to the Ben Franklin Bridge.

The overall idea: a fusion of engineering with artful practicality, of ecology with technology, and telling modern stories of the river in tandem with its history.

Local examples of Andropogon’s work (a central green for the Thomas Jefferson University campus; a master plan for the Morris Arboretum; a master plan with the Philadelphia Water Department for Lower Venice Island in Manayunk) can be seen at its Web site: http://www.andropogon.com.

Discovery through dissection

Presenting fourth was W Architecture and Landscape Architecture, led by principal Barbara Wilks, with Mark Johnson, an urban designer and principal of subcontractor Civitas, of Denver. The W / Civitas ideas were a combination of possibilities based on waterfront work done throughout the country, and detailed possibilities for Pier 11 that seemed to draw a certain amount of affection from the crowd that remained.

“Getting people closer to the water is often the goal” in such projects, explained Wilks, “taking the street, pedestrianizing it and putting it right down to the city.” She said her team likes to work with scales that blend city and nature, guided by the principle that “discovery requires new eyes to see.” (http://www.w-architecture.com)

Johnson described four “moments” for the pedestrians who will approach and encounter the pier. “You actually don’t see the water very much as you drive Columbus Boulevard, because of the piers,” he said. “It’s when you get to the end of the pier that it really becomes spectacular.”

The first moment starts between Fourth and Second streets, descending Race, “when you actually feel you are approaching the water,” Johnson said. The second is the moment when you “break out from underneath the bridge,” and your head can’t help but turn toward the water and “engage in that as a landscape.”

The third “moment” – perhaps understated, given the breadth of the street – is “actually stepping onto the pier,” he said, “because you’re moving from land to water.” Getting to the end of the pier is the fourth and final moment. “We think these zones can be treated as different places.”

That includes “piercing the surface of the pier to see what’s under the water as well.” Unlike the other three presenters, Johnson claimed that the one-square-mile pier was actually large, with a “tremendously interesting pier structure, very complicated,” a fact that can be taken advantage of by actually stripping away part of that structure to reveal cross-sections of history and architecture.

Along with an “ecology walk” at a low level, near the water and to the side of the pier, he imagines a possible “tidal pool amphitheater” amid a “network of wandering” features, loops, that could include bridges stretching horizontally over, above or through a latticework of imaginative spaces.

“Look at how many different situations there are as you move around the edge of this pier,” Johnson said. “It’s not a monotonous pier anymore – it becomes an interesting place to be.”

High Line on the Delaware

A few things about James Corner, the landscape architect who is principal of Field Operations in New York: He’s a Brit who has lived in Philadelphia for 25 years; he’s a University of Pennsylvania professor, and this past Sunday, he was featured in a two-page “Domains” spread in the New York Times Magazine – in the special infrastructure issue, no less. (Check it out here: http://www.nytimes.com/2009/06/14/magazine/14FOB-Domains-t.html?_r=1&scp=1&sq=james%20corner&st=cse)

He’s also the guy behind the High Line elevated park that just opened last week on Manhattan’s West Side, and that project was a major theme of his remarks Wednesday night.

Perhaps most significantly, Corner knows the Delaware, having been hired by the Philadelphia City Planning Commission in 2000 to do a comprehensive master plan for eight miles of the North Delaware River waterfront, from the northern edge of the city down through Penn’s Landing.

Getting a bird’s eye view of the river courtesy of a friend’s Cessna, “I was just blown away by just how beautiful the river was,” he said. “It’s blue. It’s broad. It’s enormously beautiful and scenic. … The land itself even though it was once industrial has been taken over by plants. I didn’t know that existed, and when we developed the plan, it became very clear that very few other people knew it existed, too.”

Though the High Line is 1.2 miles long over six acres, Corner said it shares similarities with Pier 11 in that its assets can be turned into economic opportunity for the city and at the same time provide a unique daily space for residents.

Corner stressed the importance of scale in designing Pier 11, incorporating the surrounding infrastructure, such as the “majesty of the bridge and the river,” but also including the water harbor space between Pier 11 and Pier 9. “These spaces in between, they lend themselves to new forms of social use, such as kayaking, or fishing. And they also have certain ecological benefits in terms of building an aquatic habitat and natural wetlands.”

Corner also cited work he’s done with two other New York projects, incorporating differing uses of the South Street Seaport area in Lower Manhattan that change with the seasons, or according to an occasion (http://www.fieldoperations.net). At Governor’s Island, he showed slides of floating swimming pools with retractable roofs, and concepts of sunken overlooks.

“Pier 11 is intended to be the catalyst for a much larger vision,” he said. Its identity is at once the creation of a destination, with connectivity and access that celebrates the water. “Pier 11 is a small but precious thing.”

As for that “Domains” feature, you’ll see that Corner’s personal tastes can be at times incongruous (favorite book: Emily Brontë’s “Wuthering Heights”; favorite movie: “The Bourne Ultimatum”). But if he gets the Pier 11 gig, take heart in what his “pet peeve about public spaces” is:

“Sameness. What makes cities great is their difference and variety. For me the best public spaces are eccentric, unique and of their time, and they don’t tend toward bland populism.”

Asked about a personal philosophy, he told the Times this: “People understand landscape as a scenic picture. For me the deeper meaning is about how your body uses landscape. So walking, cycling, gardening, all the ways you use the land, are more fundamental than just its appearance.”

What fits?

Michael Van Valkenburgh, based in Brooklyn (http://www.mvvainc.com), stressed an “incredible relative proximity to a fantastic neighborhood in nearly all directions,” as he began with a slide that asked, in small letters at the bottom, “Context? Isolation? Setting?”

It’s clear the pier is small – again, its dimensions are 80 feet wide by 540 feet long – but Van Valkenburgh really put it in context by mentioning the size of Rittenhouse Square: 560 feet by 560. Even a small playground, a volleyball court or a grouping of chairs and tables, would take away significant chunks of space, he said.

Like he did with Pier 64 at the Hudson River park, therefore, is something he’d try to replicate with Pier 11 – “to try to make it feel bigger than it is.”

Van Valkenburgh spoke mostly about Pier 64, which is similar in size to Pier 11. He showed no drawings or conceptual renderings for Pier 11, and said he would form specific ideas after engaging further with the public.

What’s next

“We were impressed by the variety,” said Avi Eden, a DRWC board member who was on the committee that selected the four bids from more than two dozen received. “What makes this exciting is that it’s really now going to happen.”

Eden said he expects a winner to be selected by the fall, and the hope is to have the pier finished by September 2010.

“The teams presented some really good concepts,” said Balloon. “I was a little concerned about how global principles will be applied to Philadelphia. Philadelphia is a unique place and a lot of these proposals seem to be based on things they had done in New York.”

Liz Emery, a civil engineer with Langan, an engineering and environmental consulting firm which would be a subcontractor on the job (for any of the four finalists), said she liked the ideas from other cities, including those from New York. “They were great – very creative, very different ideas,” she said. “It’s very exciting.”

In addition to Altman and Taylor, the presentations were prefaced by remarks from Mayor Michael Nutter and First District Councilman Frank DiCicco.

“I don’t know if this has ever been done before,” Nutter said about the process of publicly introducing four finalists for a design. He mentioned he had not yet seen the concepts, but that, “What I’m most excited about is that they’re excited.”

CLICK HERE TO SEE A PHOTO OF THE INTERSECTION

Andropogon Associates

10 Shurs Lane

Philadelphia, PA 19127

Please CLICK HERE to learn more about Andropogon Associates

Field Operations

475 Tenth Avenue, 10th Floor

New York, NY 10018

Please CLICK HERE to learn more about Field Operations

Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates

16 Court Street, 11th Floor

Brooklyn, NY 11241

Please CLICK HERE to learn more about Van Valkenburgh Associates

W Architecture and Landscape Architecture

127 W. 25th Street, 12th Floor

New York, NY 10001

Please CLICK HERE to learn more about W Architecture and Landscape Architecture

FULL STORY TO FOLLOW.

Contact the reporter at thomaswalsh1@gmail.com.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.