SugarHouse: test pilings, obstruction removal

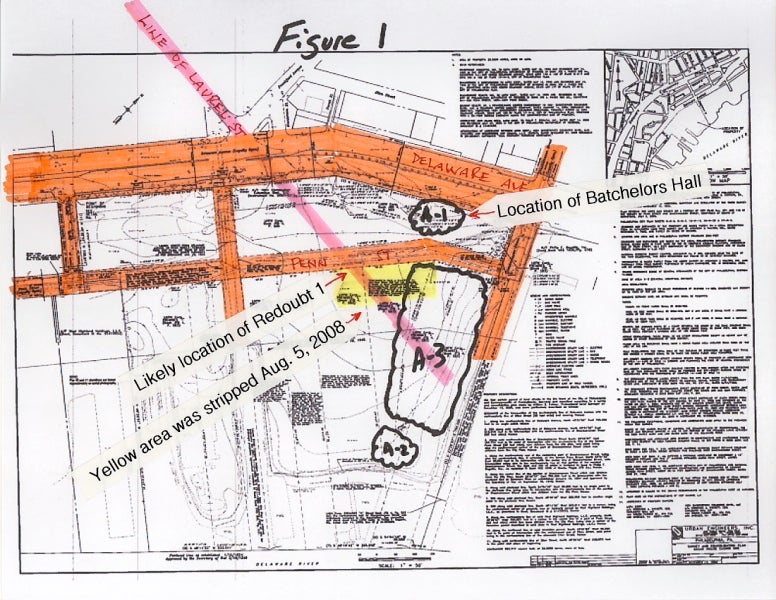

Excavations are shown in yellow. The “line of Laurel Street” is in pink. The roads are in orange.

Urban Engineers’ proposed Test Piling Sites are puffy clouds “A-1”, “A-2” & “A-3”. Courtesy Torben Jenk

Aug. 07

By Kellie Patrick Gates

For PlanPhilly

SugarHouse Casino has begun removing bricks, concrete, and other rubble from beneath the ground where a sugar refinery once stood with the blessing of the Army Corps of Engineers. The action comes much to the dismay of local historians and archaeologists who say the work puts historic preservation at risk.

The debris is what was left after the factory was imploded. “All of that has to come out. It’s an obstruction to the construction of the casino,” said SugarHouse spokeswoman Leigh Whitaker. In fact, she said, until the removal is complete, SugarHouse cannot drive any test pilings, an activity for which the Corps has also given approval. The city requires the test pilings to back up previous engineering studies about how much weight the land can hold.

Corps spokesman Khaalid Walls said it is okay for SugarHouse to start the work while a historic review – required by federal law because SugarHouse needs a Corps permit – is ongoing because neither the pilings nor the obstruction removal are happening in any areas where further archaeology is needed.

“We’ve determined that the activities they proposed don’t have an impact on our work,” said Walls.

An Aug. 1 letter sent from the Corps to SugarHouse’s general contractor says the work can be done, with certain conditions – one of which is that SugarHouse’s archaeologist, A.D. Marble, must monitor some phases of the work, document the digging, and preserve any artifacts that turn up while it’s going on.

But a group of local historians and the president of the Philadelphia Archaeological Forum – some of whom are also advisors to the Corps on the historical review of the site – strongly disagrees with the assessment that the work poses no threat to historic preservation, despite the Corps’ conditions.

For one, the consulting parties – the group of local historians, environmentalists, activists and others who are advising the Corps, have been highly skeptical of A.D. Marble’s work so far.

Torben Jenk, a preservationist, amateur historian and consulting party to the Corps, believes the obstruction removal site is just at the spot where a British Revolutionary War fort stood. And one of the places where SugarHouse plans to dig a test pile could destroy artifacts from Batchelor’s Hall – a gentleman’s social club where many prominent 18th Century Philadelphians discussed science and relaxed, and where John Bartram tended the large garden. Some of the work could also destroy evidence of Philadelphia’s historic shipping industry, he said.

SugarHouse archaeologists have reported that they looked for both the Fort and Batchelor’s Hall and found no remains of either on the site. Jenk retorts that the maps of their work do not show where they looked for the Hall. And he says the old map SugarHouse uses does not show the proper location of the Fort because it is an inaccurate copy made by someone who never came to Philadelphia.

SugarHouse stands by its maps and its archaeologists.

“It is HSP’s position that the work being done currently will not in any way jeopardize the archaeological investigation,” said Terry McKenna, project executive for SugarHouse general contractor Keating Consulting, via email. “Both PHMC (the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission) and the Corps agree.”

Kenneth Milano, a local historian who works with Jenk as part of the Kensington History Project, said he was frustrated that SugarHouse has in past archaeological reports said there was no need to do further archaeology where the sugar refinery used to stand because any artifacts there have already been destroyed, but now they say they need to remove items before they can proceed.

“They are digging deeper now than they did when looking for archaeological evidence,” he said. “It’s just bizarre to me.”

Douglas Mooney, president of the Philadelphia Archaeological Forum and a consulting party, also thinks that SugarHouse has tried to have it both ways by first saying anything worth digging for was destroyed, and now saying items underground must be removed prior to construction.

McKenna said, “The Consulting Parties are misquoting HSP’s position and deliberately misrepresenting HSP’s findings to date

“It is HSP’s position that the CONSTRUCTION and SUBSEQUENT DEMOLITION of the sugar refinery (i.e., the use of the property) destroyed any potential archaeological resources which may have been present prior to the development of the sugar refinery.”

Mooney said that prior to its demolition, the sugar factory was deemed worthy of inclusion on the National Register of Historic Places by the Philadelphia Historical Commission, but it was torn down without detailed documentation. “The only way to get anything about that site may be archaaeological remains,” he said. Mooney said the Archaeological Forum is not saying the refinery was significant, but if the city did, it should be documented.

“Mr. Mooney/PAF has stated numerous times previously that he views the subsurface remains of the sugar refinery as archaeological features. In turn, HSP and its consultants have responded that we do not agree, and have provided the evidence to support our position,” McKenna said. Mooney and PAF ignore “that the same City later issued a demolition permit for the building, and that no governmental agencies objected to the demolition of the structure,” he said.

By law, the PHMC advises the Corps on historical reviews in Pennsylvania. And due to the controversy surrounding the SugarHouse review, the Philadelphia office of the Corps asked the ACHP to become involved. The ACHP is charged with the ultimate responsibility of protecting the nation’s historic resources under the same law that requires the historic review – commonly called Section 106.

The Corps consulted with both entities prior to giving its approval for the site work, spokesman Walls said, and both said the work proposed was fine.

Jenk said he is contacting city and state officials, trying to get someone to talk to the PHMC and the Army Corps. He and other consulting parties are very frustrated because they feel that their concerns have gone largely unheeded by the Corps. They believe they should have also been consulted when the Corps was deciding whether SugarHouse could proceed with obstruction removal and test pilings.

Walls said their emailed comments were taken into consideration, but the Corps determined that a meeting was not necessary. There has been one physical meeting of the consulting parties since the process started – much has been handled via email. Walls said no further meetings are scheduled, and may not be.

Milano called the consulting party portion of the 106 process “a joke”. He called the SugarHouse permit a “done deal” and said that he has no hope left that SugarHouse will be asked by the Corps to do more archaeological digging in search of the Fort or Batchelor’s Hall.

Mooney said that the sign off of the PHMC and the ACHP mean there’s likely no chance of stopping the obstruction removal or the test pilings that will follow it. But he said there is still a chance that the Corps archaeologist from Texas who is assisting the Philadelphia office will recommend more digging after he completes his review. And Mooney said if the Corps grants a permit to SugarHouse, a Memorandum of Agreement could outline more archaeological work be done during construction.

Contact the reporter at kelliespatrick@gmail.com

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.