Infrastructure: grid as grail

(This is the sixth in a series of stories examining the infrastructure projects proposed in the Civic Vision for the Central Delaware, their cost, possible funding, and value. This story looks at one of the proposals that has sparked debate between planners and developers: extending the Center City street grid to the waterfront.)

Previous stories:

Infrastructure overview

Parks and green space

SEPTA funding

Grappling with I-95

Center City Commuter Connection

June 13

By Alan Jaffe

For PlanPhilly

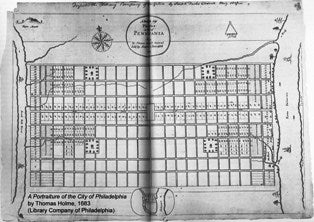

“The city consists of a large Front Street to each river, and a High Street (near the middle) from front (or river) to front of one hundred foot broad, and a Broad street in the middle of the city, from side to side, of the like breadth. …There are also in each quarter of the city a square of eight acres, to be for the like uses, as the Moorfields in London; and eight streets (besides the High Street) that run from front to front, and twenty streets (besides the Broad Street) that run across the city, from side to side; all these streets are of fifty foot breadth.”

That’s how William Penn described his plan for the city of Philadelphia, “newly laid out,” in a letter to the Committee of the Free Society of Traders in 1683. An orderly grid of streets, blocks and urban parks stretching from river to river.

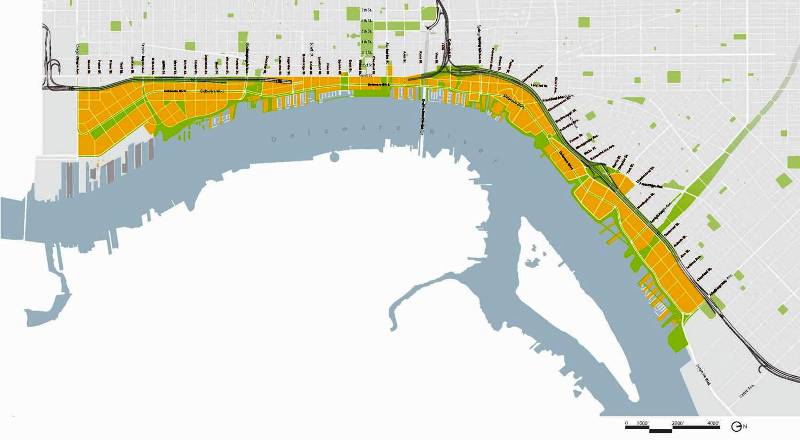

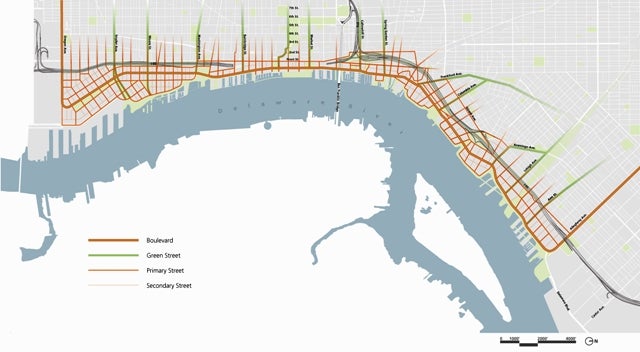

The Civic Vision for the Central Delaware takes Penn’s street plan and extends it beyond those twenty streets of Center City, building Philadelphia to the river in the north and south as well. The proposals coordinated by PennPraxis, and based on civic principles valued by residents, are meant to break up super-block-style layouts that currently exist, multiply the connections between the riverfront and adjacent neighborhoods, create continuous public access to the river, and relieve traffic congestion.

Existing conditions

The proposed street network

But the plan worries some developers who already have projects scheduled along the scenic Delaware and others who are considering projects to serve the population shift back to Center City. The street grid proposals make developers nervous about losing rights to land they own and whether they will be responsible for constructing costly new streets.

The 17th-century map laid out by the city’s founder may not be the model for modern times, according to John Westrum, CEO of Westrum Development Company. “There are rare occurrences in urban areas to gain large tracts of ground, and when the opportunity arises, one should not limit how it is planned based on the same principles used centuries ago.”

A Classical Model

Adam Krom, a transportation planner at the Philadelphia office of the design firm Wallace Roberts & Todd, and Nando Micale, a WRT principal who leads the firm’s planning and urban design group, argue that the same reasons that a gridiron made sense in the 1600s do apply today.

Penn considered how to lay out the New World city shortly after the Great Fire of London destroyed most of that metropolis. “Everyone thought this would be a great chance to have a fresh start, because London was this congested, dirty, polluted city. It stood for what was wrong with cities,” Krom said.

Architect Christopher Wren came up with a plan for a new London with a vital axis and a regularized street system. “But it didn’t happen, because essentially they rebuilt on the foundations of what burnt down. They had no concept of how to reorganize the property ownership. It was just too difficult to do.”

The plotting of Philadelphia, however, presented an opportunity to realize “the highest ideals of city planning” — access to property, an organized street grid, an orderly development of land, and careful management of city services, including fire prevention.

“Penn wanted to set out a framework that would provide equity across the city,” explained Micale. “Related to his idea of a ‘greene countrie towne,’ he assumed that each person who would have land would have equal access” to the city’s natural resources.

The concept of the city grid can be traced to Classical organization that comes from the Greeks and Romans, Micale noted. The purpose was easy movement across land of people and goods, and sometimes the military, and an equitable subdivision of property. A series of other ideal city models was conceived in Europe during the Renaissance, including one with a web of streets.

“But for Philadelphia, it was recalling that Classical, equitable, democratic form. Penn was an intellectual who was really looking, at least from his financial status, to create a democratic environment,” Micale said.

The gridiron became the norm for early planning in America on many scales. Thomas Jefferson used the model for laying out the new acquisitions in the Midwest and West. “Once you get past the Mississippi,” Micale added, “you end up with this overlay of a town development grid that goes across the country.”

In Philadelphia, the initial grid only covered the area between South and Vine Streets. Outside that rectangle other little towns developed, smaller grids called Francisville, Dyottsville and Kensington. And within the central city, the one-acre plots planned by Penn were subdivided further. “You ended up with the very fine-grained, more European architectural fabric within this gridiron, and that’s why in Old City you have these tiny streets between big streets,” Micale said. “And it occurred at the water because that’s where the economy was growing, along the trade at the waterfront.”

The logistical, democratic and economic principles that guided Penn are the basis for the Civic Vision of an extended street grid along the Delaware, Micale and Krom said.

“There are two main reasons to create a grid on the waterfront right now,” Micale said. As in Classical times, one is about movement across the land. The other is about land value.

Urban vs. Suburban Models

The current trend in traffic planning and road engineering to manage growth is the expansion of the highway with more lanes. The result is the super road, but not necessarily less traffic. “Columbus Boulevard in the south is a great example of that,” Micale said. “The road is big and there are no turning lanes. But at peak hours the traffic is still crazy.”

The boulevard is an example of a hierarchical road system, Krom said, and it is primarily used in the suburbs. “It’s like a tree: you have a trunk, and that’s the arterial street.” Collector streets branch off it and lead to local streets, but the only way to move to another neighborhood is to return to the main trunk road. “Those arterial streets have to be really large and carefully engineered, and even then they’re often congested and fail to move traffic.”

Hierachy of streets

The road system proposed in the Central Delaware plan is also a hierarchical road system, with a redesigned Columbus Boulevard still the main artery. “But it’s an inter-connected hierarchical system,” Micale said, “which allows lots of opportunity to make choices.” In the suburban model, the highways grow wider and wider; in the waterfront proposal, the lanes are distributed as a network of surrounding roads.

The grid creates “a multitude of ways to get between two points,” Krom said. “It distributes the traffic flow efficiently and is flexible and robust. If anything happens on one of those streets or intersections, there’s always a way around it.”

Octavia Boulevard in San Francisco

An example of a similar integrated network of roads was created when Octavia Boulevard replaced the highway in San Francisco, the WRT planners explained. The California Department of Transportation predicted traffic would come to a halt. “And what ended up happening is, nothing happened,” Micale said. If a problem arose on Octavia, “because it was in the middle of a grid of streets, people chose other ways to get where they were going, whether it was other highways or local streets. It is a theory of urban design and transportation planning that is about city-making.”

Rina Cutler, a former director of parking and traffic in San Francisco and the recently named Philadelphia deputy mayor for transportation and utilities, sees the practical side of the street grid plan.

In a discussion about another Civic Vision proposal, submerging Interstate 95, she recalled the 1995 tire fire that diverted traffic off the highway and into the neighborhoods. “It wasn’t pretty, but life went on,” said Cutler, who also has served as deputy secretary of the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation. “Right now, if there was an incident, that traffic is getting diverted to Delaware Avenue. But that’s why the discussion to extend the street grid to divert some of that traffic off Delaware Avenue and onto streets that don’t currently exist is a pretty useful exercise. Not just because it changes the functional use of the roadway to make it more like a parkway type of environment, but also because it allows traffic to disperse better and the city to manage congestion down there a little better.

“So if you were to ask me what I thought the biggest piece of this [Civic Vision] was, I would argue that it is the street grid that needs to be created. The street grid will actually have an impact on residents’ quality of life in a far greater number than burying I-95 will. Developers and stakeholders will have to have a voice. But is it ultimately doable? I think it is, as long as you take into account private property rights.”

Land Value

Property rights – and the possible threat to them – has been the concern of developers and land owners since the waterfront street grid was proposed. When the Civic Vision was formally unveiled in November, developer Bart Blatstein applauded the overall plan as “a marriage” of developers, planners and communities. But regarding the proposal for a grid of small public streets dividing the large parcels, Blatstein warned that “the development community would be nervous. Property owners should be nervous.”

Others worried that zoning changes to allow for a fine-grained street grid would stall or kill current projects.

But Micale said deals and projects already in place would not be affected by proposed zoning reforms. “The approvals that are in place are the approvals that are in place. It’s a legal agreement through the structure of the city that allows the owners to develop that property for a certain period of time into the future,” he said.

“For those that move forward, this city has the right, in its best interest, to work with those developers to modify those plans to conform. But while those approvals are in place, they have no legal right to change those.”

Micale noted, however, that the current housing market has slowed down development in Center City and on the waterfront. “Some of those proposals may not be appropriate proposals as the market picks back up. And if the city adopts this street grid plan, then they can affect those proposals and work with those landowners to conform to that.”

The urban designers at WRT also believe a predetermined grid would simplify land development and ensure systematic, market-friendly construction on the waterfront.

Krom refers to Battery Park City in Lower Manhattan as a model.

Battery Park City

“When that was originally started in the 1960s, it was just going to be a handful of mega-developers building sort of enclosed little projects that would be self-contained. What they found was, those projects were just too difficult and costly to bite off. The developers were too poor and the projects were too large for that economy. So they went back, years into the project, and completely redesigned it and overlaid a grid of streets –the grid of Manhattan, essentially, continued out to the waterfront.

“What they did was create a series of parcels that they then could develop sequentially, one at a time, and the market could then absorb those units,” Krom said. The city also created a public infrastructure – an esplanade on the waterfront and some connector streets – at the same time. “What that did was create a platform for investment. People could see what the cost was going to be decades before it was built out. That created market confidence that led to investor excitement to create a wide range of developments, and each developer could take on a single parcel and do a single project” that could be financed, implemented, and absorbed by market demands.

“That project is now almost built out,” Krom said. “It has been wildly successful, with some of the most expensive real estate in NewYork. That never would have happened if they hadn’t adopted this grid approach.”

The creators of the Battery Park City streetscapes also won the 2005 AIA urban design award for creating a road system that addressed security concerns in the post-9/11 world yet allowed for public spaces that are “open and inviting.”

A similar land development approach was taken in Portland, Ore., Krom said. “Portland has created dollhouse blocks,” because landowners saw that appraisals are always higher for corner properties because they have access from two streets. “They were developed to specifically maximize their profit.”

The grid adds value to property by creating that additional street frontage and access to utilities built into those right-of-ways, Micale added. It’s all a matter of “land economics,” he said.

“By laying out this road system, the value of that land is going up. The same acreage of land in the middle of nowhere, with no frontage, versus urbanized land is very different. And that’s simple urban economics.”

Curbing Creativity

John Westrum, of Westrum Development, does not believe a street grid necessarily adds value to property. He thinks it could have a negative impact on what happens at the waterfront.

A zoned street grid “would take away the value of creativity and the ability to provide something new and different versus what the rest of the city has,” Westrum said. “We are co-developing a large, 575-acre site in South Chicago. We used the grid pattern in certain areas and not in others. To mandate the grid is a real problem to any creative plan.”

Westrum said there should be “a combination” of small parcels and larger, self-contained projects. “Developers really want to sell their products. They will design the way that the market permits and encourages. Forcing someone to do something when there is the opportunity to think out of the box, and to do something creative, is detrimental to the region.”

His company is currently working on a project along the planned North Delaware River Greenway in Northeast Philadelphia. If new zoning that mandated a grid were to be imposed on that section of the city, Westrum said, “it would drastically reduce the value and the concepts of our real estate.”

Asked about retaining access to the Central Delaware for all city residents, Westrum said, “No matter what, there should be access points to the water from the main road, which is presumed to be Delaware Avenue.”

But while there “should be access at certain parts of the property so the public can get to the water,” he also said “one of the amenities of a waterfront community is the privacy and exclusiveness of those that buy or rent to have the right to access where the public does not.”

Public and Private Funding

Paying for the network of streets proposed in the Civic Vision can follow a number of different models. “That’s for the city and the developer to decide,” Micale said. “It depends on where the money is coming from. It’s different in every city.”

The PennPraxis planners have investigated the use of tax increment financing (TIF) as a way to fund waterfront infrastructure. TIF funds are used to leverage public bonds based on future tax gains to promote private-sector activity in a particular area, typically where there is redevelopment potential.

Many other cities are using TIF funds on their waterfronts, Micale said, and there is usually some specially designated entity overseeing the redevelopment.

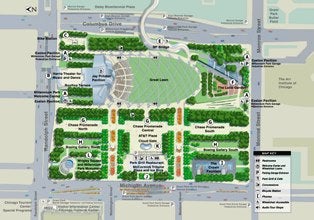

Millennium Park

Chicago has more than 150 TIF districts, and its Millennium Park was financed that way. The $340 million public investment in the park is projected to yield $5 billion in private investment in the surrounding area.

Other funding methods raised in the Civic Vision that could be applied to the street grid plan include the establishment of a Transit Revitalization District (TRID), which leverages future real-estate tax revenue to support transit-related capital projects; funding from the federal Surface Transportation Program; and the Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality Program, which directs funds for projects that reduce traffic jams and emissions.

Cities have also incorporated legislation that requires developers to finance elements of public infrastructure. Impact fees are used to address the effects of large-scale development. Developers have been required to provide capital improvements around waterfront projects in other municipalities.

PennPraxis is currently working on a detailed implementation guide to determine the best approaches for Philadelphia’s waterfront.

Opponents of the street grid are concerned about protecting their property and its value, Micale said, but “that is a defensive view of land development, because you want to do what you want to do. It goes back to more conservative values of individual property rights, as opposed to the public good.”

Land development is a “public-private system,” Krom said. “Obviously, there are tremendous public benefits that are reaped from waterfront development” following the piece-by-piece approach. “But it’s extremely profitable as well. …Because you create an orderly implementation that can be sustained over time,” he said.

“If you look at the rest of Philadelphia, it was developed following this prescription. The city platted a grid many years before development happened. Whether it was farmland or just large lots until a developer purchased it, and the city compelled the developer to subdivide according to the grid. That’s just the history of how the city was built.”

Contact the reporter at ajaffe@mac.com

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.