100 years later, we’re still learning from deadly Spanish flu

Philadelphia was particularly hard hit by the flu epidemic of 1918.

Listen 2:00

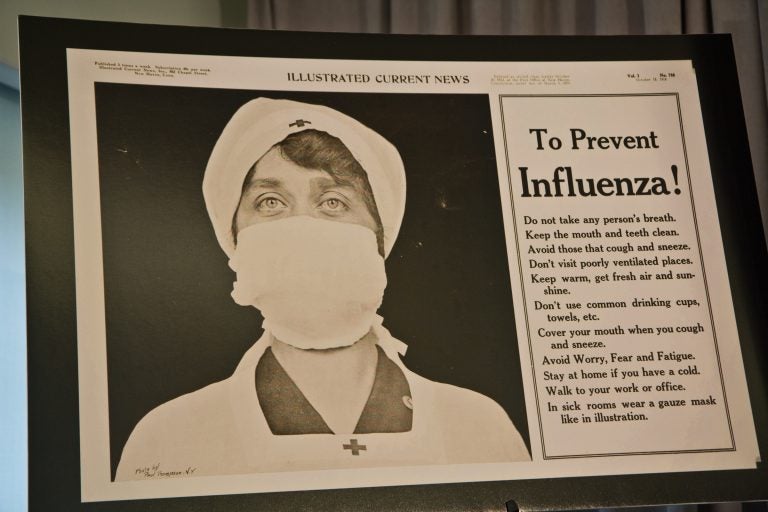

A public announcement about preventing influenza published in the Illustrated Current News in 1918 during the Spanish flu pandemic. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

In September 1918, Philadelphia was overcrowded. With the nation in the throes of the first world war, the Navy Yard barracks and boarding houses around the city teemed with people helping with the war effort.

On Sept. 28, the city hosted the Liberty Loan parade to encourage people to buy war bonds. Some 200,000 people attended the parade, among them a group of sailors from Boston who brought with them the virulent strain of influenza that became known as the Spanish flu.

The virus ripped through the city, ultimately killing about 12,000 people, making Philadelphia one of the hardest-hit cities in the nation. The people affected weren’t only the immunocompromised or the elderly. Thousands of young, healthy people were overcome by flu in a very short period of time.

“There were reports of people collapsing only hours after being sick,” said Karie Youngdahl, director of public health initiatives at the College of Physicians of Philadelphia. “Their lungs are filling up with fluid, and they’re coughing up foam and fluid from their lungs. They were drowning in their own fluids.”

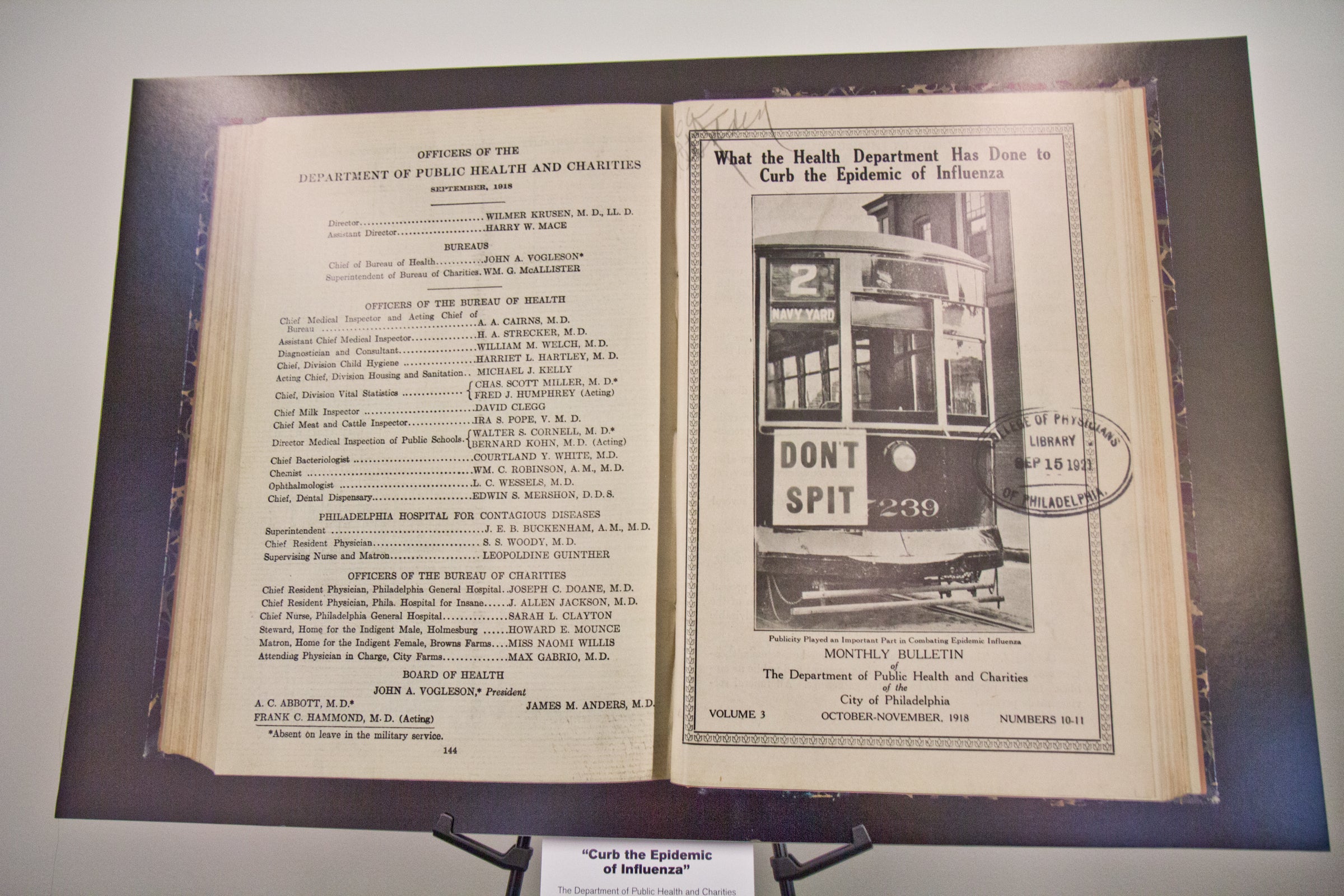

(Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

Thanks to modern antibiotics, many secondary bacterial infections that follow influenza infection wouldn’t occur today. But the flu is still deadly, killing tens of thousands of people each year and hospitalizing some 200,000 more.

Jennifer Miller of Families Fighting Flu knows the terror of those numbers. In 2012, her youngest daughter, Caroline, started kindergarten, and her oldest began third grade. Having two kids in school for the first time, she didn’t get around to taking them for their annual flu shots.

“It sort of fell off the radar,” she said.

Then one day Caroline came home with sniffles and a cough. In a matter of hours, she was panting like a dog and could barely breathe.

“She deteriorated very rapidly,” Miller said. “So there’s almost no time for the brain to process the information. You just keep thinking, like, OK, she was coughing, now she’s not breathing.

Caroline had influenza A and double pneumonia. She ended up at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and struggled in intensive care for two weeks.

Ultimately, Caroline survived, but not without a long and harrowing recovery. She needed therapy to walk and speak again, and she had to repeat kindergarten.

Quest for universal vaccine

With every shift change at the hospital, the first question every doctor and nurse asked was, “Did your daughter get a flu shot?” Miller says the guilt she felt upon answering, “No,” was overwhelming, and she has since become an advocate for yearly flu vaccination.

“You will never want to be in the position I was in,” she said, “where I had to see my child in that huge hospital bed, connected to all those wires and equipment, and know that could have been prevented if I had just gotten her a flu shot.”

Flu shots don’t always work. Last year’s was only 42 percent effective because it didn’t protect against the right strain. Experts from the World Health Organization and Food and Drug Administration decide in February what strains to include the upcoming season’s vaccine. That means a strain can mutate, or a new strain can emerge in the interim, which is what happened last year.

That’s why pharmaceutical companies are trying to develop a universal vaccine — one that would work for multiple strains over many years.

Len Friedland of GlaxoSmithKline said his company is working with the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai to develop a universal vaccine. But the nature of the flu virus makes that tricky.

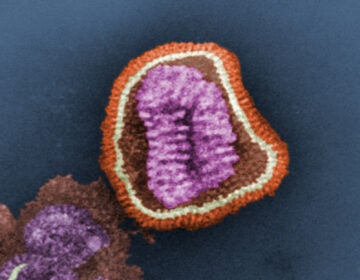

“Influenza virus is a very complicated virus in that it can change very rapidly,” Friedland said. “It mutates. It can have changes that can occur quickly and unpredictably.”

Several universal flu vaccines are being tested in clinical trials, and several groups are throwing support behind the effort, including the Gates Foundation, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and the White House’s Office of Science and Technology Policy.

But even if such a vaccine comes to fruition, it won’t be for many years. For now, doctors recommend getting a standard flu shot each year to protect against another potential flu outbreak.

“Even vaccines that aren’t super, super effective will still have tremendous benefit for preventing cases, hospitalizations, and deaths,” Friedland said. “And flu vaccines not only protect ourselves, they protect those around us.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.