In Philly’s changing Brewerytown, hope, anxiety and a very perplexing mural

Listen-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

The sun sets over Flora Street in Brewerytown (Ifanyi Bell/for WHYY)

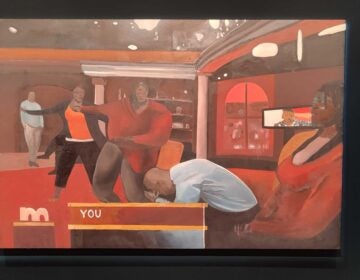

As in many Philadelphia neighborhoods, newcomers to Brewerytown love what the place might become, while long-timers rue what might be lost. On 29th Street, a painting became the symbol for those conflicted feelings.

First in series of election-year visits to one Philadelphia neighborhood in flux

One day last October, Julie Dietrich was taking her dog, a lab mix, for a walk. When she got to the corner of 29th and Flora Streets in Brewerytown, she stopped in her tracks.

What made her pause were some words on a mural being painted by two young artists on the side of a dilapidated building.

Immediately, Dietrich thought of her neighbors, longtime residents of the neighborhood, and of the Baptist church just down the narrow sidestreet.

She spoke to the artists, who turned out to be from Brazil. She asked: “Do you realize that your audience here may not appreciate that?”

That was a phrase in the center of the mural, a quote from J.D. Salinger’s novel, Franny and Zooey.

It read: “This goddam phenomenal world.”

Dietrich has lived in Brewerytown for only six years, but her sense of her neighbors’ likely reaction was on the mark.

The mural was about to become a battleground, exposing a clash of viewpoints in this changing neighborhood.

Around the Corner

Philadelphia’s next mayor will inherit a changing city, with neighborhoods in varying states of transition. What some call revitalization, others call gentrification – and they don’t smile when they say it.

Every mayor has to find a balance between the needs of newcomers and longtime residents. So, throughout this election year, WHYY/NewsWorks is going to dig into how the city’s future looks from ground level in one changing neighborhood.

We call this occasional series “Around the Corner” and it will focus on the neighborhood known as Brewerytown, a transition zone between the Art Museum area and North Philadelphia. It strings out along Girard Avenue – an eclectic mix of rowhouses and storefronts, right across the Schuylkill from the Philadelphia Zoo.

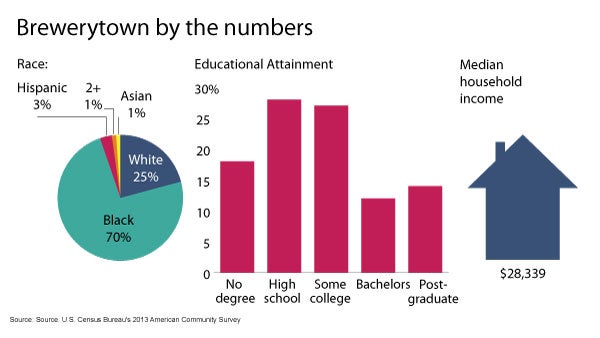

It’s been a predominantly black neighborhood since about the 1960s. Dietrich has noticed a change, though.

“There’s definitely more white people moving in,” she said. “I hate to buy into the ‘hipster’ thing, but that’s what it kinda looks like.”

If Dietrich seems a bit uncomfortable talking about how her neighborhood is changing, she’s not alone.

“It’s definitely becoming a more appealing neighborhood, but not a better community,” said André Wright, a social worker who grew up in a home his parents rented on 29th Street in Brewerytown, until rising property values chased them out in 2003.

Even the name “Brewerytown” is a sign of change. It harks back to the beer-makers, such as J&P Baltz and Commonwealth Brewing, that used to operate there at the turn of the 20th century. The name had fallen out of use until it was revived by real estate developers looking to appeal to middle-class buyers.

A lifelong resident said folks here used to call this area of town simply “North Philly.” That changed, she said, when young, white people started moving in.

A quickly changing city

A recent study by Governing magazine found that the pace of gentrification in the city – measured by home values and the number of residents with bachelor’s degrees – has accelerated dramatically, by 1,800 percent since the 1990s, according to an analysis of the study by Philadelphia Magazine.

Some neighborhoods, like Northern Liberties and Fishtown, seem to have been transformed, but the change in Brewerytown has not been dramatic — yet.

The change is more anecdotal, a feeling you get walking around the neighborhood or looking at that mural on the corner of 29th and Flora Streets.

Just hours after the mural was finished, someone covered up the ‘goddam’ in its neat, white-and-gold cursive. The offending phrase disappeared beneath smears of brown paint.

Nicole McDonald was making coffee in her apartment on Girard Avenue when her fiancé, Sam, delivered the news.

“I’m pretty sure the mural’s been buffed,” he told her.

McDonald didn’t want to go see for herself. The mural meant too much to her.

Then, she got a picture message from a friend who owns the record store across the street.

“Have you seen this?” he texted her.

Last year, a pair of Brazilian artists who call themselves “Criatipos” contacted McDonald about painting a mural in Philadelphia during a visit to America. Before the artists’ arrival, she worked with local real estate developers to find a suitable wall, on a blighted building across from a bar they had recently rehabbed.

When Criatipos came to Philadelphia, it was McDonald’s job to show them around the city. They even crashed on her living room floor for the week.

“They just kept saying that they really loved the city, they loved the energy, they loved the neighborhood,” she said, “And I just kept thinking, ‘They’re doing this for free. This is incredible.'”

This mural was a big deal for McDonald, who is not an artist herself, but a passionate curator who has organized other art projects in the neighborhood. She grew up in a small town in Minnesota and saw the mural as a way to give back to this place where she’s lived for a year and a half after stops in a half dozen other cities like Chicago and Austin. Philadelphia, but more specifically, Brewerytown, she said, is the place where she’s felt most at home.

The second day of painting, McDonald’s cell phone rang. It was the artists telling her someone from the neighborhood was not happy.

When McDonald arrived, Penny Brown, the Flora Street block captain was there on behalf of some neighborhood churches that were offended by the artists taking God’s name in vain – especially with children living nearby.

McDonald and the artists tried to mollify, saying that the curse word wasn’t so bad because J.D. Salinger had left off the final “n.” McDonald also did academic research on the word, brought her own copy of Franny and Zooey to the mural site and even enlisted another local pastor to help explain their side of things.

None of it soothed Brown, who said she was most offended by the fact they didn’t consult the community before putting up the mural.

“It was a quote that was meaningful to [the artists],” said Brown’s neighbor, Julie Dietrich. “It had no meaning to their audience and that was where they went amiss.”

However, the battle lines around the mural were not evenly drawn by race or time in the neighborhood. Some longtime residents liked the image and appreciated the message.

“It IS a goddam phenomenal world,” said André Wright.

‘Changing faces, changing people’

The mural controversy captures the awkward phase Brewerytown is living through.

You can see it walking down the Girard Avenue business corridor – the corner store next to the check-cashing place across the street from the artisanal pizza shop and tattoo parlor, both “coming soon.”

Warren Hill has lived in a family-owned house on the 2900 block of Girard most of his 53 years. Growing up in the 1960s and 70s, he remembers when Brewerytown still had breweries.

Back then, it was a self-contained neighborhood where residents could get anything they needed on the avenue: clothing and work uniforms, shoes, eyeglasses.

“We had one of the oldest candy stores in America – Young’s candy store,” Hill remembers, “There wasn’t a piece of candy in that store I didn’t try. The chocolate covered coconut, the caramel, the peppermints.”

But don’t mistake Hill for someone consumed by nostalgia. He accepts and even likes redevelopment, so long as it benefits everyone.

Hill spent 12 years in the U.S. Marine Corps, where he was stationed in places like Philippines, Japan and Thailand. He says his travels have given him a different perspective from some of his neighbors.

“Changing faces, changing people, changing racial boundaries is not dramatic – it’s an every day event,” he said. “Throughout history it has happened and it’s not gonna stop now.”

David Waxman is one of the people behind Brewerytown’s changing aesthetic. He’s a developer with MM Partners, which has been buying up properties here since the early 2000s – including the bar across the street from the mural.

Waxman’s office on N. 30th Street is a modern building with high ceilings and echoing rooms.

It used to be a crack house.

He said Brewerytown satisfies the first rule of real estate value: location. It’s close to Center City and convenient to the highways that take cars to and from the suburbs of Philadelphia and South Jersey.

“[It’s] really the same reason that it was a great open air drug market in the ’90s and early 2000s before redevelopment came here,” Waxman said.

The crack epidemic hit these blocks hard in the 1980s, as it did other Philadelphia neighborhoods. The dealers flocked in just as the good factory jobs were flowing out of the city. The decades of blight that followed created opportunity for developers like Waxman.

Walking around the neighborhood, he points out rows of formerly blighted buildings his team either tore down to build anew or rebuilt from their bones.

At 29th and Girard, the business corridor starts. Waxman walks past the pizza shop and tattoo parlor, a new coffee bar and a bicycle shop. MM Partners’ name is on them all.

Perhaps this is what Julie Dietrich meant by the “hipster thing.”

Waxman knows his work could have consequences for the longtime, lower-income residents, but he wants the changes to be “organic,” resulting in something few neighborhoods actually achieve:

“A neighborhood where working class and middle class and even upper-class people can live together,” he said.

Waxman sees a direct connection between the future of this neighborhood and the upcoming city elections. Will his new, young tenants stay here once they have school-aged children? Will the tax abatements that have encouraged redevelopment continue? Waxman believes what happens next in the neighborhood will depend a lot on who the next mayor is and who is on the City Council.

So the real estate developer is paying attention. However, others in this neighborhood seem disconnected from the process.

Longtime resident Ron El, who lives on 29th Street, was stumped by a question about what he thinks is at stake for Brewerytown in this election year: he doesn’t know yet.

“These politicians, they got a lot of game,” El said. “I’d like to believe ’em, but a lot of times, I hate to say this – it’s for themselves.”

‘Just painting without asking’

After the word ‘goddam’ disappeared beneath that brown paint, Nicole McDonald tried to take the conversation in a different direction.

She brushed over the brown with black chalkboard paint and invited the community to write what they would like the mural to say instead.

About five months later, all that’s on the black patch are a graffiti tag and the suggestive image of a woman.

McDonald said she learned from the experience and still sees the person who painted over the ‘goddam’ around the neighborhood, although she won’t say who it was.

“I’m sure that they view what I did as the same thing,” she said. “Just painting without asking them first.”

McDonald and her fiancé plan to buy a house in Brewerytown, but she’ll wait a while before doing any more art projects there.

She says it’s not her turn to make a mark.

Brewerytown is just one Philadelphia neighborhood undergoing intense changes. Join NewsWorks on April 21 at WHYY studios for a public discussion, “Philadelphia Neighborhoods in Flux,” to dig into what neighbors throughout the city want from city leadership. The event is free and open to the public, but registration is required.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.