Philadelphia safer from job-stealing robots than peer cities, report says

If you work in Philadelphia, your job may be safe from the robots that pundits predict could put one-third of U.S. workers out of a job by 2030.

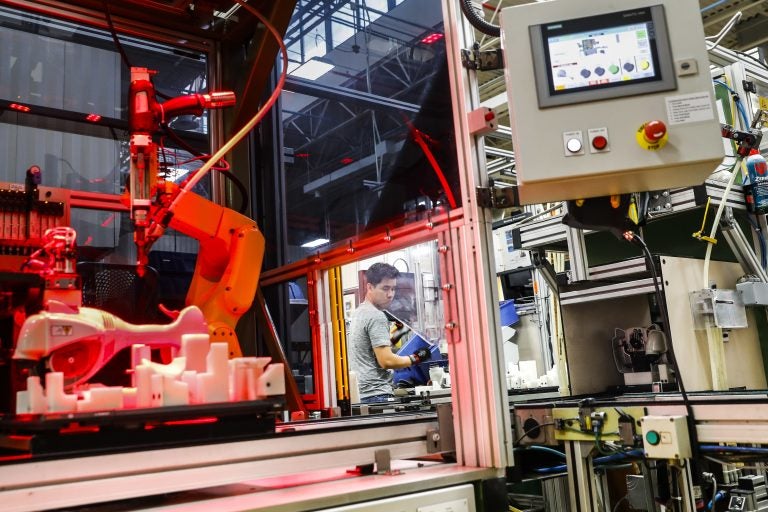

In this 2017 photo, an assembly line laborer works alongside a collaborative robot, left, on a chainsaw production line. (AP Photo/John Minchillo)

This story originally appeared on PlanPhilly.

—

If you work in Philadelphia, your job may be safe from the robots that pundits predict could put one-third of U.S. workers out of a job by 2030. You just may need to switch careers.

Or at least that’s the latest analysis from a team of researchers out of the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia who say that the city is better positioned than peer cities to weather the automation revolution that has already begun to disrupt the economy nationally, as employers replace human labor with machines that can do the work more cheaply.

“In the Philadelphia [region], as long as fewer than approximately one out of three workers holding high-risk jobs lose their jobs in the next decade or so, there could be enough new jobs available to workers displaced by automation,” wrote the Federal Reserve Bank authors in an October report.

To be clear, machine automation has already begun to shake up certain parts of the local economy, especially low-wage sectors. The trio of Philly Fed authors — Drs. Lei Ding, Elaine W. Leigh, and Patrick Harker, president of the Fed branch — found that 18 percent of jobs in the city are at high risk of being automated, close to par for the national average. Leading the pack are positions like cashiers, receptionists, and fast-serve cooks — jobs held disproportionately by women and racial minorities. The trend line points to a risk that automation could deepen racial and gender inequalities seen across the city.

“It could potentially,” Harker said in an interview. But, he notes, it’s easier for economists to predict what jobs will be lost than which new careers might be gained by technologies. “How many drone operators do you think we needed 10 years ago?”

Harker and his co-authors conclude that if and when those new jobs arrive, Philadelphia — compared to cities with lower wages in Delaware, Southern New Jersey, and elsewhere in Pennsylvania — will be much better positioned to absorb the positive effects of the automation wave.

“Relatively wealthier areas, such as the Philadelphia and Trenton [region], have the lowest share of jobs at a high risk of automation [in the region], whereas areas with lower wages are more likely to be hit harder by the coming changes,” they wrote.

The researchers used Bureau of Labor Statistics data to create a metric for predicting the future job opportunities for workers threatened by automation — in other words, a figure that balanced projected job loss with the potential for growth opportunities in low-skill occupations. This “breakeven adoption ratio,” as they call it, takes into account the current job growth rate in Philadelphia to paint a picture of the automated workforce that doesn’t look overwhelmingly dreary.

“If we assume labor forces remain consistent and don’t change, then as long as we lose less than one out of three of those high-risk jobs in the next few decades, there could be enough jobs created to overcome the loss,” said Ding. “For example, in Philadelphia [region], half a million jobs will be at high risk but another 160,000 new jobs will be created in the next 10 years.” As with any prediction, Ding tosses in an important caveat. “The breakeven adoption ratio also has a lot of assumptions,” he said.

Part of the reason for the relatively brighter outlook for Philadelphians is due to the city’s booming “Eds and Meds” sector. For every fully automated McDonald’s popping up around the world, there’s a host of professions in the higher education and healthcare sector centered around human traits like creativity and empathy which replication by technology remains unlikely — and they happen to be at the heart of local economic growth.

“Maybe in some future like the Jetsons we could have Rosie the [robot] nurse, but that set of skills can’t be automated yet,” said Harker. “There’s a technical set of knowledge you need as a nurse, but you also need to double-down on the human skills.”

But amid the optimism, the report acknowledges the threat of unequal prospects for certain populations. For example, low-skill workers could be hit with wage loss or hours reductions, even if they’re not fully unemployed. Another threat comes with a changing geography of labor brought by technological advances. “Jobs are changing both in content and geography due to automation,” said Harker. “They’re no longer in the stores in Center City; they’re in some logistics warehouse out by the highway. Those changes are occurring right now.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.