Winning by a single vote? Happens all the time

Despite national attention on a Philadelphia man who won an election judge post with a single write-in vote, it's not uncommon. We explain how it works.

Listen 3:15

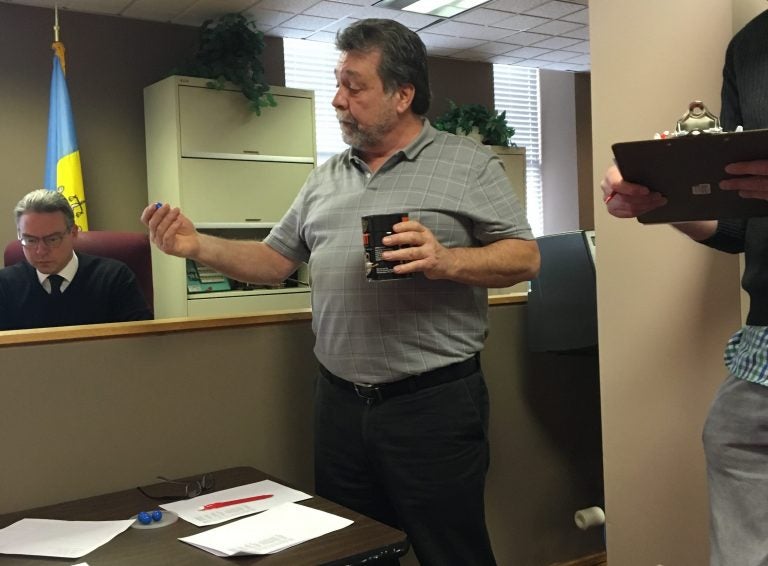

Philadelphia Acting Supervisor of Elections Kevin Kelly breaks a tie in an election board race by drawing numbered tokens from a coffee can. (Dave Davies/WHYY)

Manayunk graduate student Phillip Garcia had a moment of fame this week when the Washington publication The Hill ran a story on how Garcia won a Philadelphia election board seat with just one vote. It turns out that’s not such a novelty.

A tweet about Garcia’s one-vote victory to become election judge at a Philadelphia polling place got more than 58,000 favorites on social media.

They say that one vote doesn’t matter, but I literally wrote in my own name and won an election because I guess no-one else ran/voted for this position. pic.twitter.com/43iam09Inp

— p.e. garcia (@AvantGarcia) December 1, 2017

But Al Schmidt, co-chair of the Philadelphia city commission that runs elections, said he’s seen this plenty.

“It’s actually quite common,” Schmidt said in an interview. “We had 71 judges of elections win through one write-in vote” in the Nov. 7 election.

Every four years, Pennsylvania voters cast ballots for three members of their local election board — those folks who sit at folding tables at polling places and run our elections. That’s 1,686 elections in Philadelphia alone.

Besides the 71 single-vote election judges, there were more than 30 ties for election board posts, nearly all among candidates who had just one vote each.

Ties were resolved Tuesday at a commissioners’ meeting when Acting Supervisor of Elections Kevin Kelly drew numbered tokens from a coffee can.

The handful of candidates who showed up, including Jesse Breitbart, could pluck their own.

“I picked a one!” Breitbart said after picking his winning token to the applause of the commissioners and their staff. “Thank you, thank you, it’s an honor to be a minority.”

Breitbart won the post of minority inspector for his polling place in West Philadelphia.

When candidates run for election inspector, the election code provides that the top vote-getter becomes majority inspector, and the runner-up the minority inspector.

It’s intended to ensure two different parties are represented, but in some Philadelphia precincts Republicans are scarce, and the election board can be all Democrats.

Schmidt says all of the posts can be hard to fill, including that of election judge.

“We have, still, after that election about 500 of those positions where nobody ran for judge of elections,” Schmidt said.

That’s right. For 500 precincts, nearly one out of three in the city, nobody ran for election judge, and nobody wrote in his or her name.

That’s also not unusual, Schmidt said. Election board members have to attend training sessions, then work 14 hours on Election Day for $100 — before taxes. So it can be hard to recruit people.

There are two ways to fill empty election board posts. With the signatures of three voters from your precinct, you can get a court order to occupy one of them.

Or, Schmidt says, there’s another way.

“The election code in Pennsylvania provides for something called a curbside election,” Schmidt said. “That means that the people who assemble at that polling place at the time the polling place is opened organize themselves, and have a vote amongst themselves to determine who’s going to do what on Election Day.”

It sounds stranger than it is. What really happens is that people in the community, some recruited by the city commissioner staff, trade phone calls and agree to volunteer to show up for Election Day duty.

Somehow, it mostly works.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.