Watching over the land in Canada’s Great Bear Rainforest

First Nations communities in British Columbia are training indigenous people to manage local natural resources.

Listen 8:53

Chantal Pronteau has been a Kitasoo/Xai'xais Coastal Guardian Watchman since 2015. She patrols about 1,500 square miles of inlets on the Canadian coast. (Irina Zhorov/WHYY)

On a beach on Calvert Island, off the central coast of British Columbia, Canada, about a dozen people crouch, digging in the sand, bluffs and evergreen forest at their backs. They’re having a bit of fun now but are learning real crime-scene-investigation type skills that they might use in the future. Earlier — just for practice — they dug molds in the beach in the shape of peace signs and stick figures, then filled them with casting material. Now they lift the shapes out of the sand. One day, they may have to use their new know-how as a detective might, to inspect boot prints and tire marks left behind in the woods.

The exercise is part of a two-year program to teach members of First Nations communities skills to work as stewards of their land. They’ll work on issues ranging from bear poaching to tracking salmon numbers and responding to oil spills.

Last year, after decades of negotiations between the First Nations, forestry companies, environmental groups, and the Canadian government, new logging limits on timber were approved along British Columbia’s coast and the islands just off it. The conservation-minded protections came out of a long campaign to more holistically manage the area, dubbed the Great Bear Rainforest. First Nations communities have lived in the temperate rainforest, using and caring for the natural resources there, for thousands of years. Now, management of those resources is growing more formal.

As part of that, in the 1990s, First Nations started drafting management plans for their territories, outlining strategies to protect biodiversity and local culture. The health of the environment and people here have been inextricably linked. Locals rely on the water for food, and the region’s wildlife dominates the stories that make up nations’ foundational beliefs. One of the first to release a plan was the Kitasoo/Xai’xais. Doug Neasloss, the nation’s chief councilor, said his community made clear to him that the plans don’t mean anything without monitoring and enforcement.

The Great Bear is really remote, much of it accessible only by plane or boat, and resources are limited. Neasloss says they knew they couldn’t rely on the Canadian government to take on monitoring.

“My community said, ‘Don’t let someone else clean up your house,’” Neasloss said. They created a team to patrol their territory, what eventually became known as Coastal Guardian Watchmen. Many of the communities who live in the Great Bear Rainforest now have their own guardian watchmen.

Authority

Chantal Pronteau has been a Kitasoo/Xai’Xais Guardian Watchman since 2015. Her jurisdiction encompasses about 1,500 square miles of inlets, which cut through a folding screen of gunpowder-grey mountains speckled with trees, and which provide habitat for bears, seals, and whales. Pronteau says before guardian watchmen began to regularly patrol these inlets, hunters, fishermen, and tourists came and went as they pleased.

“It was like a big zoo,” she said.

Now she spends her days making sure no illegal hunting happens and that fish catches follow regulations.

At the end of the year, the watchmen map their daily patrol routes. “If you put all those GPS routes onto a big map of our territory you can see that literally everywhere is painted red,” she said. She says regulators from federal agencies may have one or two patrol lines to show for the whole season.

Despite her constant presence on the land, Pronteau says visitors test her. She recently approached a fisherman who initially refused to show her his license.

“He said, ‘Well, you’re not DFO’” — DFO is the Department of Fisheries and Oceans, a federal agency — “‘We’re not going to give you my license. Do you guys have the authority?’ And I said, ‘Well, you can think of it any way you like, but yes I do have the authority, because I work for the local First Nations. We manage this area.’”

But the Guardian Watchmen don’t have the same authority as federal officials. Elodie Button is a training coordinator for the Coastal Stewardship Network, which trains watchmen for participating First Nations. She said “the authority that the Guardian Watchmen have is grounded in indigenous law and the laws of their nations.” The Canadian Supreme Court has acknowledged indigenous law in landmark decisions, but jurisdiction remains complicated. “And so currently the majority of Guardian Watchmen programs work with an observe, record, and report capacity. So they’re monitoring for compliance, but they’re not enforcing compliance,” Button said.

That’s changing. “Guardian Watchmen are working with increased authority and are assuming increased responsibility,” Button said. In 2016, the Canadian government for the first time provided funding for watchmen programs, affirming their importance, though it’s not clear yet how the $25 million will be used.

Documenting to preserve

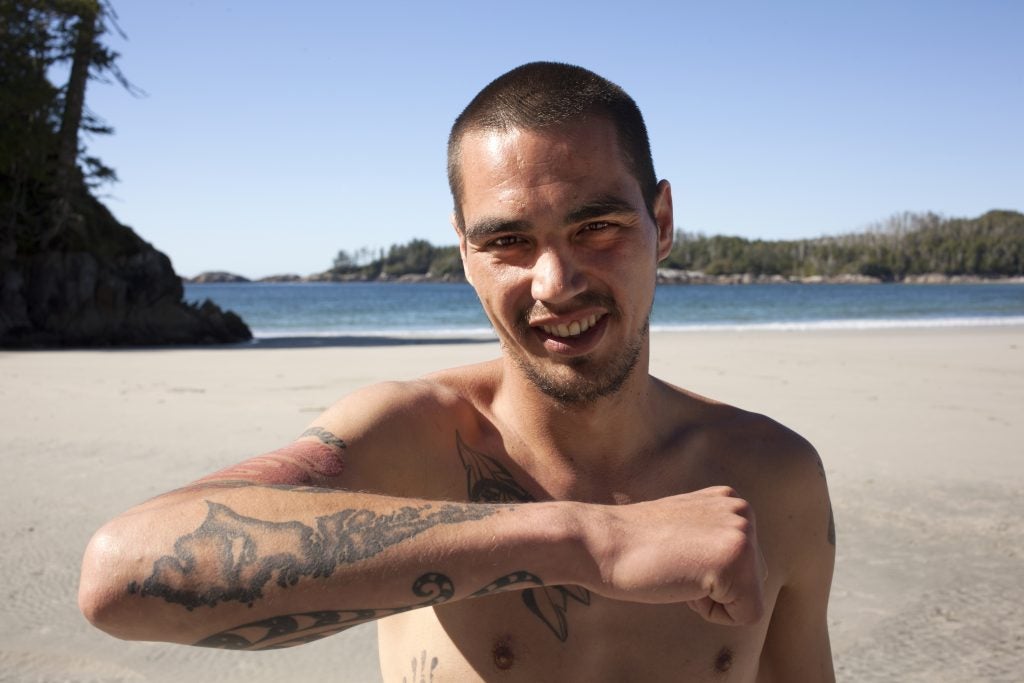

Back at the training for stewards on Calvert Island, Jordan Jones holds up his arm and points. He has the Haida Gwaii archipelago, his home, tattooed on his forearm and he runs his finger along the map to show where he works. Jones is part of the mapping department on Haida Gwaii. His team combs the land documenting biodiversity; rare plants used in Haida medicine; cultural landmarks, like old village sites, canoes abandoned in the forest, or CMTs, culturally modified trees that were cut into by his ancestors some hundred years ago.

The records he creates document the Haida’s culture and history, but he says they could also be used to assist in negotiations with the federal government. “If the government tries to take the land back, we say ‘You can’t do that. We have so much CMTs there.’”

When he found his first canoe, belonging long ago to his Haida ancestors and now disintegrating on the mossy forest floor, he got a tingly feeling down his back.

“It’s our land, and we gotta protect what we have left before anything happens to it. So that’s all I think every time I’m in the bush and out on the land: Just gotta protect what we have left. Because we don’t have much for being a Native person, right?”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.