Penn doctor releases fictional encyclopedia of imaginary diseases

Listen

The Afflictions explores causes

Imagine a kind of amnesia wherein everybody forgets about you (Amnesia inversa). Imagine a disease that causes you to contract the infirmity of your neighbor, as your neighbor assumes yours (Renascentia). Imagine becoming so comfortable with the sensation of death that ultimately your spirits gently leave your body (Mors inevitabilis).

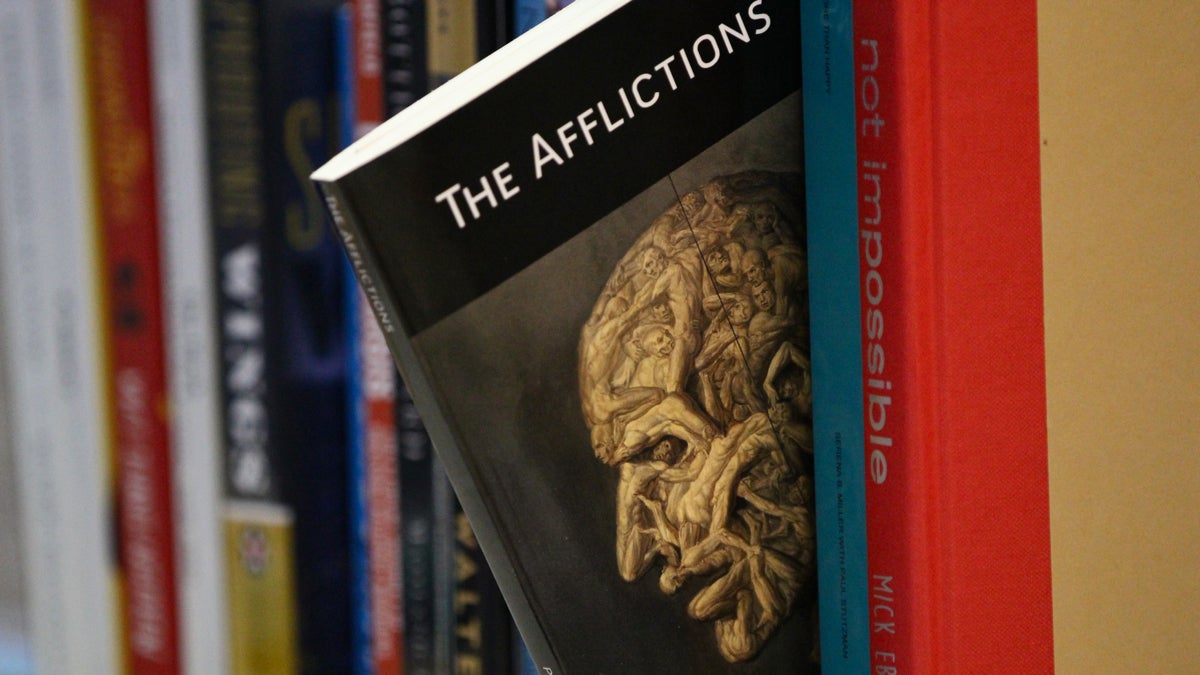

These are imagined diseases compiled in “The Afflictions,” a work of fiction based on a 16th century medical encyclopedia – the 375-volume Encyclopedia Medininae – housed in an medieval library in Portugal.

That, too, is made up.

“The Afflictions” is the first published work by Vikram Paralkar, an oncologist at the University of Pennsylvania specializing in cancer of the blood. In whatever spare time he has when not researching cancer and treating patients, he likes to write fiction.

“I’ve always been passionately interested in reading fiction. I discovered Calvino, Borges, and Gabriel Garcia Marquez at 18,” said Paralkar, referencing his magical realism influences. “I wanted to capture ideas in beautiful language.”

The ideas he is closest to are medical. The 50 diseases described in “The Afflictions” – some complete with cures and case studies – can be read as bizarre, gruesome fables that hint at medical issues.

Take the aforementioned Renascentia, wherein neighbors meet in their village church once a year to find out where the “divine dice” rolls, taking away pre-existing maladies from some and assigning them randomly to others.

Some leave with freshly pockmarked faces, others with new obstructions in their bowels. Some receive dementias or epilepsies of fulminant afflictions that wrack them with agony even as they rise from the pews. And others are cured of consumption, their amputated limbs grow back, or their pustules vanish.

“One of the ideas this disease tries to explore is the arbitrariness by which diseases are given out to people,” said Paralkar. “If this were to happen, on a single day of the year, you were to get a completely new set of diseases, you would consider it an awfully unjust system. But is it any more unjust than what exists now? People are allotted their own random set of diseases.”

The imagined text on which “The Afflictions” is based – the Encyclopedia Medicinae – is written as though it were lifted directly out of the Age of Enlightenment, when science and religion were still easy bedfellows.

The disorder known as Persona fracta, or Fractured Person, is a psychosis wherein the invalid believes every body function is controlled by a separate person. Paralkar created a case study of a suffering seamstress who understands that walking is done by the walking seamstress, breathing by a breathing seamstress. Her body houses the talking self, the eating self, the looking self, an infinite number of persons each of whom step forward when needed.

The seamstress is not actually suffering. She functions perfectly normally, if a bit crowded. The problem is theological: if she believes her body functions are a collection of dissociated pieces, it stands to reason her soul is the same. When the body falls apart, the soul follows. That notion goes against the church’s insistence on the perseverance of the soul in heaven.

“In the 16th century, any explanation you proposed, you had to grapple with ideas of god, heaven and hell,” said Paralkar. “I decided to utilize that to the fullest. Anytime a disease that veered into theological implications, I dived into that area.”

The world that Paralkar created, based in part on the history of medicine and in part by imagination, is one that makes sense. He wrote brief summaries of 50 diseases, all of which describe a single malady. The meta-affliction in “The Afflictions” has something to do with being fractured and displaced, with the center not holding.

In his day job as an oncologist, Paralkar, the scientist, realizes that disease does not make ethical sense, nor theological, nor moral sense.

“Its intrinsic to people that we find a moral purpose to things,” said Paralkar. “Especially with cancer, people ask – why did this happen to me? The answer is because cells divide and sometimes they make mistakes. That answer is immensely unsatisfying. It’s just the way we are programmed, we try to find reasons and patterns.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.