Looking for love deep in the brain

Listen Photo via ShutterStock)" title="mri" width="1" height="1"/>

Photo via ShutterStock)" title="mri" width="1" height="1"/>

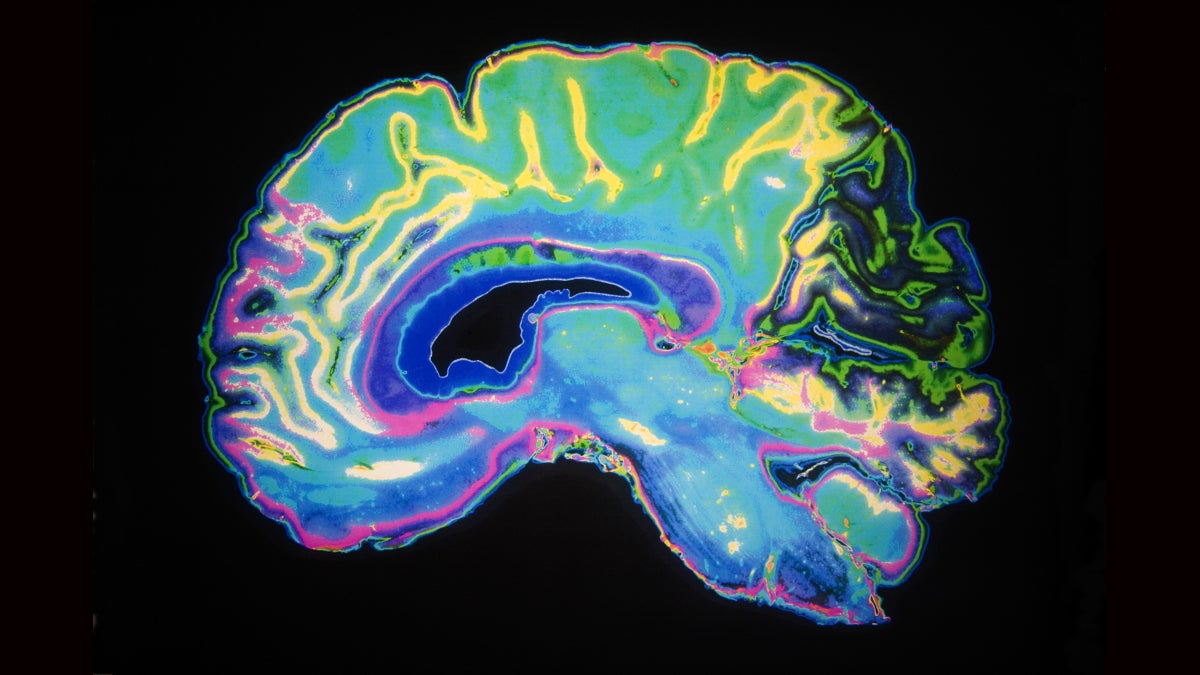

An artificially colored MRI scan of a human brain. (Photo via ShutterStock)

Technology provides proof that some stay madly in love long into a relationship.

Falling in love is a universal experience, well-documented in poems, plays and ballads dating back thousands of years.

In more recent history, researchers have attempted to take a more scientific approach to documenting the impacts of love. In their most famous finding, a research team led by anthropologist Helen Fisher used functional MRI brain scans to show that a primitive part of the brain called the ventral tegmental area is activated when people are newly in love.

“It’s part of what we call the reptilian core of the brain associated with wanting, with motivation, with focus and with craving. In fact, the same brain region where we found activity becomes active also when you feel the rush of cocaine,” Fisher said in a 2008 TED talk.

This finding got international media attention when it was published in 2005, with headlines like “Falling in love is like smoking crack cocaine.”

Since then, Fisher has become the face of the scientific study of love. But it is her research partner, Albert Einstein College of Medicine neurology professor Lucy Brown, who is responsible for the brain science behind these discoveries.

Brown had spent much of her career studying the brain’s reward systems when, in 1996, Helen Fisher asked her to use the relatively new technology of functional MRIs to peer inside the brains of those newly in love.

“To reveal the brain systems of romantic love, even just to find out if there was such a thing,” Brown said. “This is a hugely important part of life… and no one had tried to understand it.”

For their initial study, Brown’s team put 17 college students into functional MRI scanners and showed that this primitive part of the brain, the ventral tegmental area, lit up in scans when the subjects looked at pictures of their partners. That “lighting up” represents increased blood flow and activity in that primitive region. The results made Brown start thinking about love not as an emotion but as a drive.

“It’s like hunger or thirst,” Brown said. “It’s really part of our survival system, which was in a way kind of a surprise.”

The honeymoon phase can last forever

Psychologists have long known that for most people, the fluttery feelings of first love morph into strong attachment a few years into a relationship. Brown’s anecdotal observations show that as that happens, this primitive part of the brain stops being activated and other parts of the brain responsible for deeper attachment light up.

Based on research questionnaires, however, psychologists have also found that a minority of long-married people say they still experience this obsessive love decades into a relationship.

“And they wondered, were these people really in love in the same way?” Brown said. “Or did they have some need to say they were, were they lying on the questionnaires, you know, what’s going on?”

To find out, Brown’s team recruited another 17 people, this time those who had been married decades but said they were still “madly in love.” Their claims turned out to be measurably true: their brain scans showed activation in the primitive VTA, similar to those newly in love.

“I remember when I saw that first result, I said, ‘Wow she says she’s in love with him still just as she was in the beginning, and she is,” Brown said. “I must say that I myself didn’t think it would be possible to be married that long and still have that same kind of obsession feeling.”

Scientist as subject

While Brown was researching this obsessive love, she was falling for someone herself. She was a widow, he a widower, and it was love at first kiss.

“Realizing what was going on in my brain kind of enriched the experience,” Brown said. “I was thinking, I know how this is going to take over my life!”

A few weeks after they got married in 2010, Brown decided to turn the brain-scanning tables and do an fMRI on herself, as a gift to her new husband, Herb.

As she expected, the ventral tegmental area lit up red on her scan. But another result surprised her.

In her brain scan, a big blue patch appeared in the front part of her brain, showing decreased activity in the region responsible for negatively judging other people. A small study from her research group had recently shown decreased activity in that region early on in a relationship was a good predictor that the relationship would last.

“I had felt that it was going to last, but somehow, it’s funny, it is a good feeling when you see that physiological effect that’s totally at an unconscious level that you know is a good predictor,” Brown said. “It does kind of help to solidify the feeling that, ‘This is going to last.'”

Brown repeated the scan two years into her marriage, curious about what would change over time. The VTA activation was gone, as she expected. She was not among the minority of people who stay “madly in love” well into a relationship.

“And I’m sad to say that the deactivation, the suspension of negative judgment isn’t quite as prominent as before, but it’s still there,” Brown said.

Love research has practical applications

Fisher and Brown’s research has spurred other findings that go beyond self-discovery.

Anna Zilverstand is a researcher at Mt. Sinai in New York who has studied the resting brains of those newly in love.

“We were interested in finding out how the brain works when we are feeling positive emotions, in order to learn how we can maybe stimulate these positive emotions in people who have difficulty feeling them,” Zilverstand said.

This approach is called neurofeedback, and Zilverstand said it has had some preliminary success in treating depression by showing people their brain activity while in a scanner.

“It has been shown that people can learn how to modulate these brain regions that are active during a positive state, and then hopefully this is going to lead to them also feeling better,” Zilverstand said.

Lucy Brown has a more philosophical motivation: she believes it is important to understand the power of love so neither it nor heartbreak is brushed away as trivial.

She plans on scanning herself about once a year, so she can become the first case study on how love changes in the brain long-term.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.