How Chicago is improving HPV vaccination rates

ListenChicago’s three-dose coverage level for teen girls is 53 percent, that’s up from about 37 percent the year before.

Chicago, Washington, D.C., and North Carolina have done what lots of other places haven’t: bumped up the number of teens protected from HPV, a virus that causes cancer.

Last week, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that just 40 percent of teen girls and 22 percent of boys across the nation have finished the three-dose course of shots. Coverage rates for other recommended pre-teen vaccines are much higher, and the government’s goal for HPV is 80 percent coverage by 2020.

The human papillomavirus is the most common sexually transmitted infection. In the vast majority of people, the virus seems to clear the body but causes cancer in a small percentage of others.

“The problem is, we don’t know who will get cancer,” said Rachel Caskey, a pediatrician and vaccine researcher at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

Public health experts say that’s why the vaccine is recommended for everyone.

Doctors first worried about HPV’s connection to cervical cancer in women, now they are documenting many cases of HPV-related head and neck cancers in men.

“This is not about just having a cervix. This is not important to only half the population,” Caskey said.

Caskey is part of an effort in the long list of things the Chicago Department of Public Health is trying to do to boost HPV vaccine rates.

The department tracks individual rates and issues a report card—of sorts–to doctors and nurse practitioners. Then Caskey meets with them to talk about how they’re doing compared to colleagues around the city.

It seems as if she’s a bit of an enforcer for the department’s mission to up vaccine rates, but Caskey says it’s more accurate to say she offers ‘gentle encouragement.”

“There’s no stick. It’s much more of a carrot,” she said.

They talk about in-office systems to remind clinicians to offer the vaccine, and ways to send appointment reminders to patients. Caskey also gives clinicians pointers on how to talk with parents about the vaccine.

When the HPV vaccine was first introduced, Caskey says lots of well-intentioned doctors over explained the benefits, maybe because they were trying to overcome distrust and confusion.

“By doing that for just one vaccine sends a message that it’s different,” Caskey said.

Parents notice when the doctor is anxious, so Caskey encourages clinicians to relax a bit.

She wants providers to recommend the HPV vaccine, the same way—and on the same day–they recommend all the other adolescent vaccines. But in the end, she’s pragmatic about the challenges and sympathetic to all that needs to happen in a busy practice.

“I say look, ‘this is a three-dose series, the sooner you get all three, the quicker you are protected. However, two’s better than one, three’s better than two. If it takes us three years to get ’em done, it takes us three years to get ’em done,'” she said.

Less is more

As part of the strategy to increase coverage rates, Chicago recognizes primary care providers who’ve achieve the results city health officials want. From Chicago’s south side, pediatrician Cesar Menendez got an award in 2014.

For girls, his HPV vaccine rates were 90 percent for the first shot, 70 percent for all three.

“I like to say it’s because of my convincing attitude,” Menendez said.

He is charming—you’ve got to love an old-school physician who still gives out lollipops—but Menendez says top to bottom his practice is designed to make sure kids get their immunizations.

“The doctor sets the mindset for the office and everybody on is involved in this,” he said. “That’s the only way it’s going to work.”

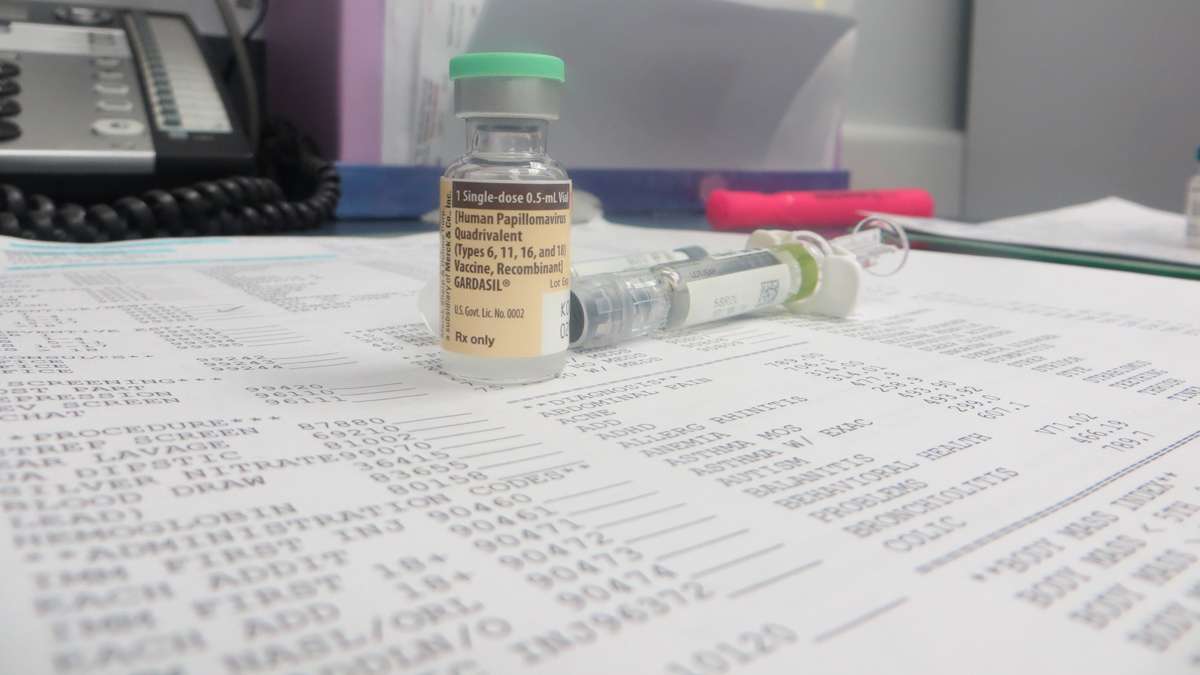

Kids need all three doses of the vaccine to be fully protected from HPV. The recommended schedule means families have to come back to the doctor’s office two more times within a year.

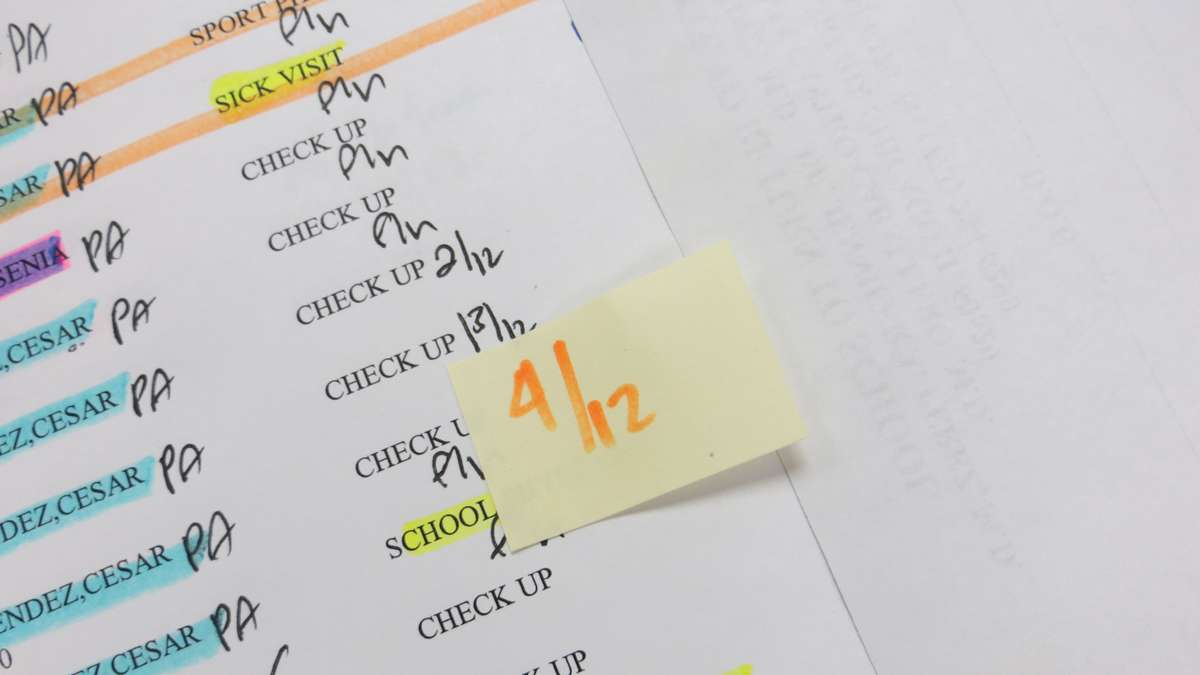

When Menendez sees a patient who’s 11 or 12, his office staffers put a sticky note reminder right on the medical chart to prompt the doctor to offer the immunizations.

“They annoy me, but they do a good job annoying me,” he said.

The office has electronic records and a system that could be set up to send digital alerts, but that hasn’t been needed.

“You don’t need to be spending millions of dollars on a system that doesn’t help you,” Menendez said.

When fifth grader Anthony Rivera comes in with his mom and younger brother—the family hears about the HPV vaccine three times.

Menendez mentions it. The medical assistant who gives Anthony the injection says she’ll see him again in two months. The front desk receptionist mentions it again as the family is leaving. And, Anthony’s mom will get a reminder call the day before he’s due for shot number two.

There’s lots of repetition but the delivery is routine. Menendez talks about the vaccine the same way he talks about seat belts and bicycle helmets.

“If they have questions, we answer the questions,” Menendez said.

But there were no questions about HPV from Anthony’s mom, and no complaints from Anthony—even though the HPV shot does sting a bit more than other injections.

A complicated message

Chicago Health Commissioner Julie Morita says parents seem more confident about accepting the vaccine when clinicians use the “less is more” approach to recommend the vaccine.

Still, many parents have lots of questions and concerns.

The HPV vaccine has a good safety record, but early on, there were bitter, political fights over efforts to mandate the vaccine.

The immunization was cleared for use in the United States in 2006—and initially recommended for girls. Later the federal health official updated their advice: boys are supposed to get the vaccine too.

That added confusion for a vaccine that public health experts admit had a bumpy introduction in the United States.

Caskey says she thinks most pediatrician primary care providers follow the CDC recommendations and offered the HPV vaccine to pre-teens but a few have opted out when parents in their practice strongly oppose the vaccine. No doctor wants to strain the trust she has with parents, she said.

“They just felt a little bit overwhelmed by that and it was very time consuming during the visits to have to have these long dialogues and they then decided, ‘I’m not going to vaccinate against HPV; it’s just too much work,'” Caskey said.

Plus, the sex thing complicates health-communication efforts: HPV spreads through intimate contact.

People don’t want to think about their 11-year-old having sex—even if that sex is way off in the future. So, some families say ‘no’ to the vaccine, or put it off for a few years.

Morita says HPV vaccine is recommended for adolescents because the goal is to get protection onboard before they become sexually active.

“We don’t wait to vaccinate children until after they’re exposed to diseases,” she said.

Last year, Chicago won an $800,000 CDC grant to test new vaccine strategies. The city spent part of the money on an awareness campaign including public-service announcements on radio and TV.

Philadelphia received a similar CDC grant and in the latest survey, it leads the nation in HPV vaccine coverage rates.

“If there were a vaccine to prevent cancer, wouldn’t you want your child to get it? HPV vaccine is a cancer prevention vaccine,” Morita said.

Chicago’s three-dose coverage level for teen girls is 53 percent, that’s up from about 37 percent the year before. Morita says it’s a big win.

“I have to admit, my 12-year old didn’t get his vaccines on time because it was hard to get him back into the office cause he’s playing basketball, baseball, he’s got science club–we couldn’t get him back in on time. And I forgot. And I’m highly motivated,” Morita said.

She’s the health commissioner now but for most of her 15 years with the health department, Morita lead the city’s immunization program.

The health department is still analyzing its efforts and can’t say yet which tactics have been most effective.

Between the ages of 9 and 26

The government wants children vaccinated at age 11 or 12, but the reality is, lots of kids don’t get the vaccine until high school.

That’s late, but not too late. The CDC says the shots can be given to anyone age 9 to age 26.

At Proviso East High School in Maywood, Illinois just west of Chicago, lots of students get their first HPV vaccine during their back-to-school freshman physical, or at a sports check-up for cheerleading or football.

“It is an uphill battle, number one – parents will go along with anything that is mandated to keep their child in school. Your measles, your mumps, your chicken pox, tetanus, all of those things. No brainer, parents sign the consent, but something that is not mandatory, that has not been around for years and years that the parents themselves are unfamiliar with—they’re cautious about because these are their kids,” nurse practitioner Colleen Andreoni said.

She said she wishes there were more community conversations to help her explain the connection between HPV and cancer to parents and kids.

“So they are aware of that before they come in to see me,” she said.

Andreoni cares for kids at Proviso’s school-based health center, which is operated by the Loyola University Chicago School of Nursing.

About two-thirds of the school’s 1,800 students are registered to get primary care at the health center, which is on school grounds but separate from the traditional nurses office, Andreoni said.

When a student is due for his or her follow-up vaccines, Andreoni’s patients are just down the hall, but there’s a better way to reach them.

“Texting is really the way to go with students, don’t even bother making a phone call,” she said.

Andreoni guesses that 30 to 40 percent of the health center’s female patients have had the HPV vaccine.

Often the acceptance and diffusion of a new medical innovation into society takes time.

Health center project director Diana Hackbarth says in her opinion, the HPV vaccine probably needs to be mandatory for school.

Hackbarth, who’s a public-health nurse at heart, wears stylish glasses and her all-white hair is cut into a chin-length bob. She was a nurse before seatbelts were required and a part of the fight to make child-safety seats mandatory. It took 30 years to get Chicago to ban smoking in public spaces, she said.

Asked what it will take to protect more people from HPV-related cancers: Hackbarth said: “I don’t have 30 more years here.”

“As more people are informed about it, then that’s going to make the difference,” Hackbarth said. “Most people most of the time recognize the value of vaccines and protecting their children and their loved ones, I think this just needs to be put in that context.”

This story was produced with support from the Solutions Journalism Network, a nonprofit dedicated to reporting on responses to social problems.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.