The redemption of Viking: Did the 50-year-old mission to Mars find life or not?

How NASA’s 1975 mission to Mars led to decades of scientific controversy and confusion over the existence of life on Mars — and why that’s starting to change.

This story is from The Pulse, a weekly health and science podcast. Subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.

Find our full episode on space exploration here.

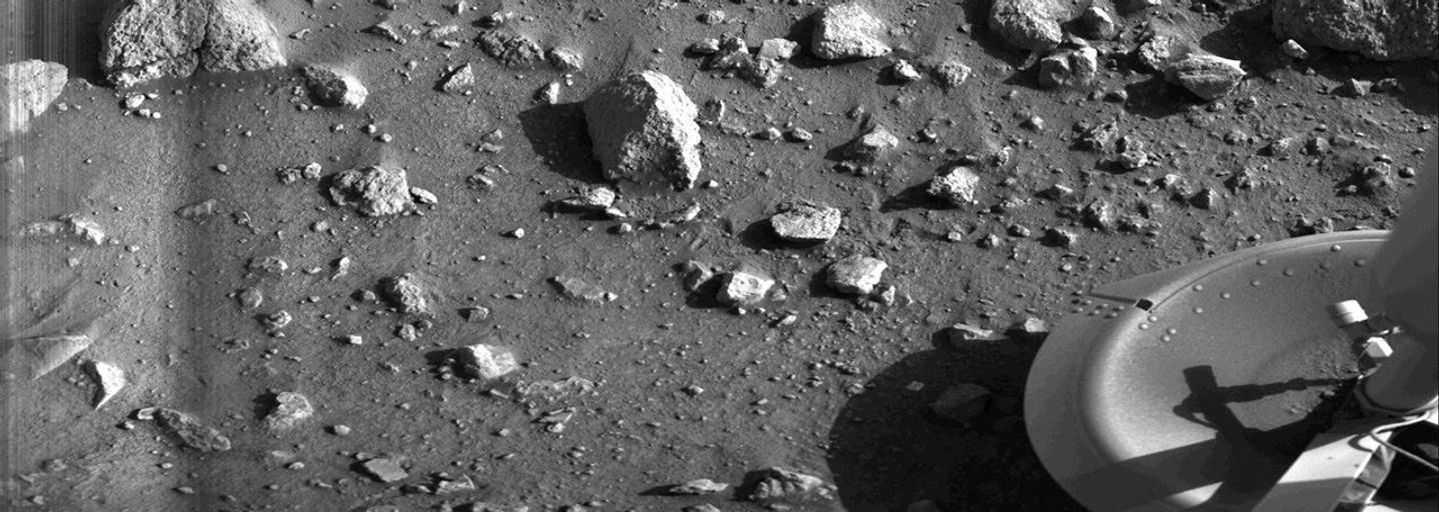

It was the morning of July 20, 1976, when the NASA Viking team received the first photo they — or anyone — had ever seen of the surface of Mars.

“We were sitting there and watching the first picture develop of the surface of another planet — from that surface of the other planet,” said Joel Levine, a research professor at the College of William & Mary, whose 41-year career at NASA began with Viking. “And I remember at one point, one of our scientists named Carl Sagan said something to the effect of, ‘Wouldn’t it be interesting if we see elephants or giraffes walking across the field?’ Of course, he was kidding. And of course, we didn’t see that, but it was very exciting that we were seeing something that no one’s ever seen before.”

The photo was being transmitted by Viking 1 — an autonomous, uncrewed probe that had just become the first-ever craft to land on Mars’ surface. Rachel Tillman, the daughter of another Viking member, James Tillman, who worked on Viking’s Meteorology Science Team, remembers it being a slow process.

“The images themselves took forever to actually come in because it’s one pixel at a time,” she said.

Tillman — now an aerospace historian, and founder of the Viking Mars Missions Education and Preservation Project — was watching from the cafeteria of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California, along with her mom and brother.

“The initial imaging coming in was just incredible tension, because it wasn’t happening fast and nobody knew what we were looking at,” she said. “And so we’re all going, what is that? What does that look like?”

The image, when it finally appeared, was as prosaic as it became iconic: a black-and-white, panoramic photo of the rocky surface of Mars — and, in the bottom right corner, Viking’s own footpad.

Fifty years later, it’s one of the big moments that still stands out to the people who worked on, and those who closely followed, Viking – but it wouldn’t be the last. The Viking mission was momentous in a lot of ways: first successful landing on Mars, first exploration of the Martian surface, and — most significantly at the time — the first NASA mission dedicated to what remains a central question of space exploration: Are we alone? Is there life on other planets?

It’s a question that would prove harder, and more controversial, to answer than anyone expected — leading, in the decades since, to Viking being largely forgotten by the public; relegated to the scrap heap of missions from a bygone era.

But in recent years, some scientists have begun reassessing Viking’s findings — in a way that could not only reshape its legacy, but affect how we approach the search for life, and even future crewed missions to Mars.

The origins and challenges of Viking

If you ask Candy Vallado what the ultimate goal of the Viking mission was, she puts it this way: “Mars or bust.”

That was literally the slogan that she remembers hanging on banners around the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, where she worked as a software engineer, helping to design Viking’s onboard computers — back in the days when mainframes ran on punchcards and could take up most of a room.

“We still had big mainframes, and the different Viking teams would come in and they would need X amount of compute time,” Vallado said. “And so we would have to allocate them CPU slices. All stuff that nobody even thinks about now, but that’s what we had to do.”

It’s just one example of the clash between technological limitations and the audacity of Viking’s mission — audacity that was rooted, at least in part, Joel Levine said, in the success of the moon landing a few years before.

“NASA had just landed two humans on the surface of the moon,” Levine said. “And NASA was looking [at], what do we do next?”

After a series of meetings, Levine said, advisory committees decided that the next big step should be a soft landing on Mars, in order to conduct research on the planet’s surface.

“And the major scientific problem to be searched for, or to be attempted, is, ‘Is there life on Mars today? Or was there life on Mars in the past?’”

The question wasn’t just a means of generating public interest, or satisfying idle curiosity — according to Levine, the answers could have real implications for the eventual fate of Earth.

“We know that 4.6 billion… years ago when the solar system was formed, Mars was very similar to Earth,” Levine said.

It was home to rivers and lakes, a thick atmosphere, and oceans five miles deep — but then, something fundamental shifted.

“Something happened on Mars that we don’t fully understand that transformed Mars from an Earth-like planet with plenty of liquid water and a thick atmosphere to the Mars of today — no liquid water at the surface and a very, very thin atmosphere,” Levine said. “And the question is, what happened? And more important, does it tell us something about the future of the Earth? How the Earth may evolve?”

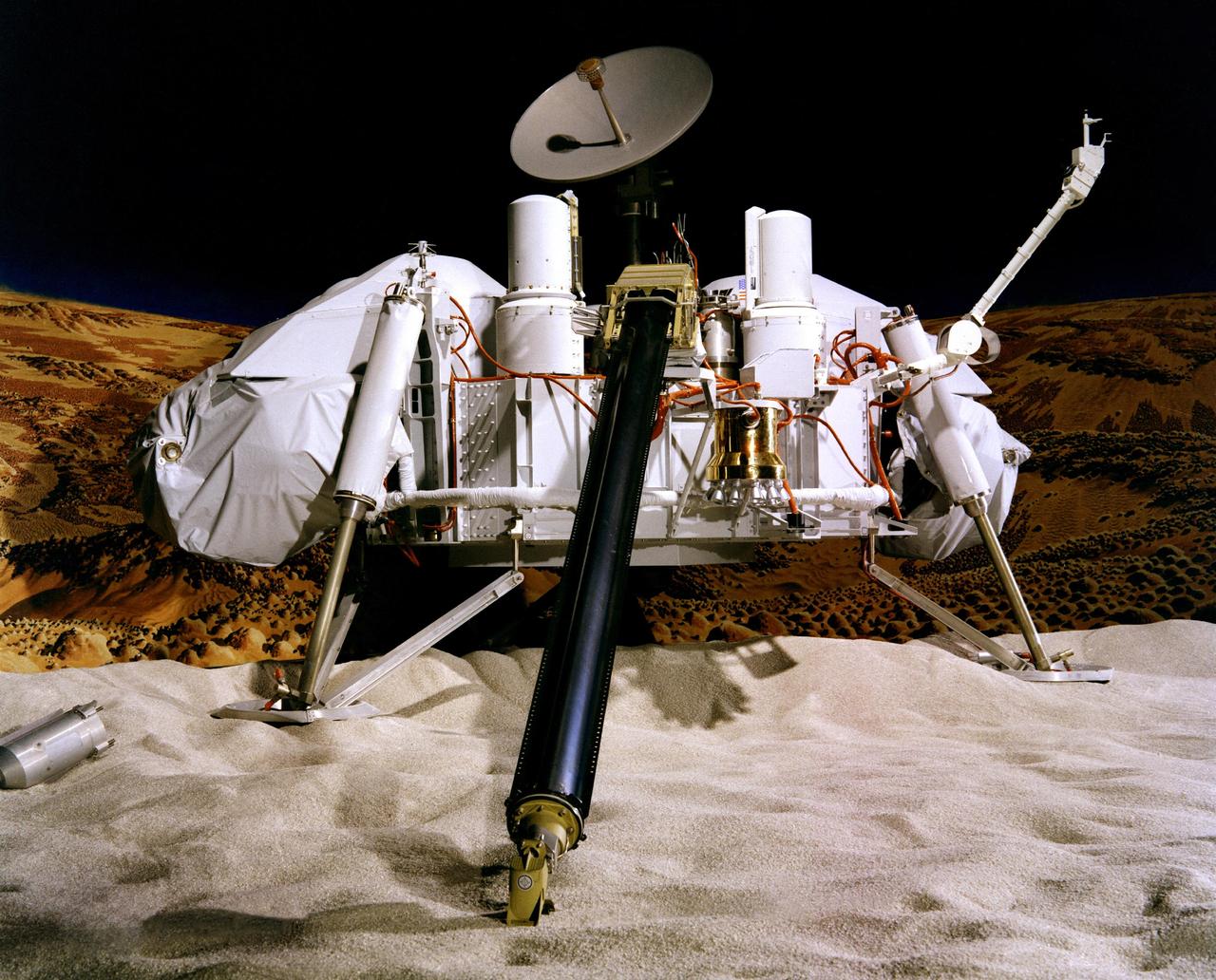

These big questions were supposed to be answered by two robotic probes — Viking 1, which would land first, and Viking 2, which would arrive a couple months later. The probes were identical, each about the size of a small car, and made up of two parts: a squat, hexagonal lander with three legs and a robotic arm for digging soil, and an orbiter with four windmill-like solar panels attached to a boxy satellite.

The plan was to deploy them to Mars, a nearly yearlong trip, send them down to the surface, and have each spend 90 days gathering data and conducting experiments. If it sounds like a simple mission — it wasn’t. Because, despite previous flyby and orbiter missions of the planet, we still knew very little about Mars.

“We did not know what the surface was like physically,” Tillman said. “We didn’t know if it was sandy, or if it was a fine powdery dust surface that you could sink into for 3 or 4 feet. We didn’t know if it was hardpacked. In fact, we didn’t even know how large the rocks were on the surface because we couldn’t get a high enough fidelity image of the surface to know, are we going to hit giant boulders when we land? So we knew very, very little.”

Subscribe to The Pulse

And that presented a lot of problems when it came to planning the mission.

For one thing, astronomers knew almost nothing about the composition of Mars’ atmosphere — which made descent modeling incredibly tricky. What they did know was that its atmosphere was incredibly thin — less than 1% as dense as Earth’s atmosphere. That meant it would be a lot harder to put the brakes on during descent, so that the Vikings didn’t end up crash landing on the surface.

“We’re coming into the atmosphere of Mars at a very high speed, 14 or 15,000 miles an hour,” said Levine, who worked on atmospheric modeling for the mission. “Pretty, pretty, pretty, pretty fast. And six minutes later, you have to be traveling one or two miles an hour to do what we call a soft landing.”

The team eventually figured that one out, by developing a special, supersonic parachute — one that was not only capable of inflating in such thin atmosphere, but also wouldn’t fall apart while traveling at 14,000 miles

But that was just the beginning of the puzzles they needed to solve. Another big challenge was the fact that the Vikings had to be fully automated, since there was no crew. NASA wouldn’t even be able to help pilot the craft remotely because Mars was so far away that there was a 20-minute lag in communication between the landers and Earth.

“As a result of that, they had to land without the assistance of humans, because there was no way that you could do any course correction,” Tillman said. “If you determined that you were going too fast and you were going to hit something, it would be too late, because we’re 20 minutes away. So they had to create the very first autonomous descent vehicle.”

And then, there was the actual building of the probes, which needed to be able to withstand extreme heat — and not only because of the friction of descent.

“In those days, we had a planetary quarantine,” said Nelson Freeman, who helped develop the computer systems that would get the Vikings from orbit down to the surface.

Planetary quarantine was a relatively new idea — essential to the mission’s central goal — that Freeman summarizes this way: “That you don’t bring life with you if you’re going to search for life on another planet.”

That meant that, before launching, the entire craft would have to be “sterilized” in special chambers that could heat up to more than 230 degrees Fahrenheit for a full 40 hours — a requirement that affected not only the outside of the craft, but the computers inside.

“Any normal electronics that were built in those days, 240, 234 degrees would have just cooked everything and we’d have had mush sitting around,” Freeman said. “So the challenge was to be able to design hardware that could withstand that.”

That meant developing special circuits that were capable of withstanding that kind of heat. Freeman also had to work around the computers’ extremely low memory.

“In those days, the onboard computer had only 18,000 words of memory,” Freeman said. “And that’s what we had to come up with the entry and descent landing software, as well as all the software that was going to run the mission.”

And it had to do all of that with very little power — just 70 watts.

“So that’s about two-thirds of an incandescent light bulb,” Freeman said. “And that included being able to communicate, run every subsystem, and be able to send data from our lander up to the orbiter for relay back to the earth.”

Part of what made these challenges extra stressful was Viking project manager James Martin’s notorious “top 10 problems list.”

“If you ended up being on one of the top 10 problems, you got all kinds of extra visibility, not only within the company, but also within NASA, all the way up to NASA headquarters,” Freeman said.

Freeman got direct experience with that kind of visibility when one of his team’s own projects made the list — and stayed on it for 29 months.

“There was just a lot of pressure,” he said. “And we got to the place where it was a real question whether the computer would be [functional]. It didn’t get off the top 10 list until a few months before we were going to launch for Mars.”

Candy Vallado, on the other hand, remembers her time working on Viking as being filled with energy and excitement, despite the challenges.

“We didn’t think of it as tough — it was just like, that’s the job, we’ve got to do it,” she said. “It was like every day was a new challenge, a new obstacle, a new problem to solve — not an obstacle, a problem to solve. And you thought about it 24 hours.”

NASA eventually managed to solve all those problems — but, at the time of Viking 1’s launch, on August 20, 1975, arguably the biggest challenge was still yet to come: successful descent and landing.

Viking’s ‘rocky’ descent and landing

Joel Levine remembers one Viking engineer characterizing the difficulty of Vikings’ descent and landing this way: “There are a thousand different processes that must happen in sequence to within a fraction of a second accuracy.”

“I would say at least 80% of the individuals didn’t think that both landers would land successfully,” Tillman said. “And there was a lot of question if either of them would, because there were so many potential failure points. We’d never been in the atmosphere with a spacecraft. The Soviet Union had sent three spacecraft in advance of us, and they’d all crashed. So, there was a lot of reason to think that it would potentially crash.”

The angle had to be right. It had to slow down fast enough to avoid a crash landing. It had to land softly enough not to disturb the surface, since they’d be performing experiments there looking for biologic materials. And they had to find the right place to land — which the team had already done based on photos from the Mariner missions, only to discover their original site wouldn’t work.

Viking 1 was originally scheduled to land on Mars on July 4, 1976 — America’s bicentennial. But when the orbiter began taking measurements of the site, the Viking team realized it wouldn’t work.

“There were boulders, there were big rocks — it was not a good area to land,” Levine said.

But NASA was facing considerable pressure from the White House to “stick the landing” on July 4, due to its patriotic significance.

“Jim Martin, the project manager, said, ‘We will not land until we’re ready to land. And we’re ready to land when we know that we have a safe landing site,’” Levine recalled.

Finally, after a couple weeks of scouting, the Viking team found the right spot — and, after an agonizing 20-minute wait, discovered that Viking 1 had achieved the soft landing they were looking for on July 20.

Not long after came the transmission of the first photo of and from Mars’ surface, and then, the real purpose of the mission: the experiments.

What Viking’s biological experiments found

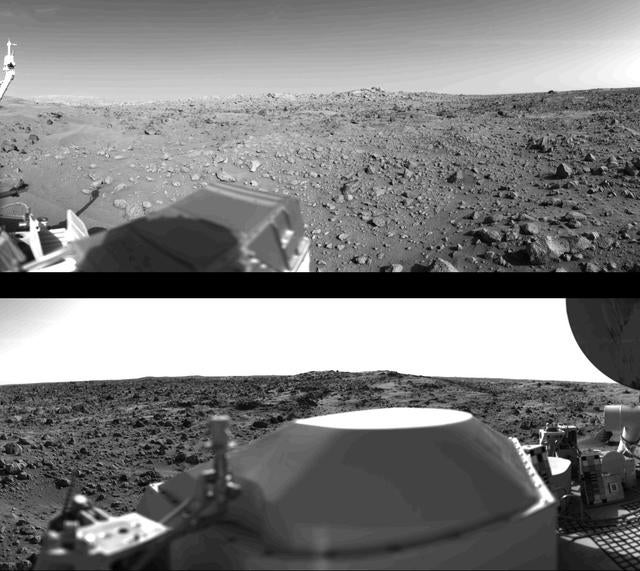

One goal of Viking’s research was simply to learn about Mars. And so, over the following days and weeks, Viking 1 systematically analyzed the atmosphere, studied the soil’s physical and chemical composition, and took pictures of the planet’s surface.

But arguably the most highly anticipated — and, ultimately, controversial — experiment was the first of four designed to test for signs of life: the labeled release experiment.

The way it worked was this: First, Viking 1 scooped up a sample of soil, and transferred it to a sterilized chamber inside the lander. Next, they sealed the chamber and provided the soil sample with “food” — a nutrient solution “tagged” with the radioactive isotope carbon 14. If there were microorganisms in the soil, the idea went, they would eat the food, and produce carbon dioxide as a byproduct. If the lander’s instruments detected carbon dioxide — and it was radioactive — they would know it had been produced by those microorganisms’ metabolic processes.

“And sure enough, that’s what the labeled release experiments measured,” Levine said “They began measuring radioactive carbon dioxide in the chamber.”

It was an absolutely momentous finding — or, at least, it might have been.

But there were other experiments designed to search for life, including one that relied on a gas chromatograph–mass spectrometer (GCMS), an instrument capable of identifying organic molecules. It did that by heating the Martian soil to temperatures high enough to vaporize its component chemicals, separating the resulting gases, breaking the molecules of each gas into fragments, and measuring the masses of those fragments to identify them. Had it found evidence of organic molecules, it would’ve bolstered the findings of the labeled release experiment.

And the experiment did find trace amounts of organic compounds — chloromethane and dichloromethane — but in such small amounts, and in forms so similar to those found on Earth, that the team concluded that they must have been the result of contamination from cleaning solvents.

“The results were not consistent with biological activity,” Levine said. “And the project scientist, Gerald Soffen, used this experiment and its negative results and said, ‘Look, if we can’t find organic material on the surface of Mars, there can’t be life.’ And even though the labeled release experiment gave evidence of what we thought was microbial life, without the presence of organics detected by the gas chromatograph-mass spectrometer, there could be no life on Mars.”

It was a disappointing conclusion – one that Tillman says she believes hurt Viking’s reputation and ultimately its legacy.

“That was very difficult for them and for the mission itself, because with that announcement, a lot of the attention was then off of Viking altogether,” she said. “People stopped paying attention. And that meant that all of the other data that was still being gathered was really not given the limelight, was not given the attention that it deserved.”

It also, Tillman says, created what many people considered a black eye for NASA.

“The Viking mission itself has been badmouthed — The Viking mission has been badmouthed by scientists and engineers all across the globe, including NASA employees since then,” she said. “Because they said it failed to find life, which is not accurate. Nonetheless, professionals continue to use that very simplistic statement to withhold the recognition from Viking that Viking deserves.”

Revived controversy over the labeled release findings

But not everyone agrees with the conclusion that Viking failed to find signs of life. In fact, over the last few years, several researchers have started rethinking the results of the labeled release experiment — including Steve Benner, an astrobiologist who’s been looking into the Viking findings since 1999.

“The story is, as it’s actually reported, that the GCMS, as we abbreviate it, did not find organics in the soil,” he said. “But, in fact, it did.

Benner first got interested in reinvestigating Viking’s findings while participating in peer review sessions that NASA was holding at the Lunar and Planetary Institute in Houston.

“And in the evenings we had free access to the library, and at the bottom of the shelf of the library was many volumes of the NASA Viking mission logs, which I read through,” he said.

Benner had read about the experiments in the past, in textbooks and review articles, all of which said that Viking had failed to find life.

“But if you read the logs, that’s not what it says,” Benner said. “All these life detection results were positive.”

Benner has been investigating and writing about the contradiction ever since — and insists that Viking actually did discover organics on Mars.

So why the conflicting results? Benner argues that the GCMS simply wasn’t sensitive enough to detect the tiny number of microbes that would’ve been present in a resource-starved environment like Mars, as we’ve seen by using it in other, similar environments like deserts.

Benner has been making this argument for years, without much success. He even published a paper in 2000, hypothesizing that there was some substance in the Martian soil that was slowly oxidizing the organic materials, thereby making them undetectable to Viking’s instruments. And in 2008, he appeared to be proven right — after another mission discovered the presence of a chemical compound called perchlorate on Mars.

“So what is in fact going on, and we’ve known this now for 15 years, is they did see organics on the surface — but the problem was that the surface also contained perchlorate,” Benner said, adding that, when heated alongside organics, perchlorate can cause an explosion. “Perchlorate burned the organics before the instrument had a chance to see them.”

So if all this is true, why didn’t more scientists besides Benner and a handful of others make the same connection?

“No one wants to make predictions about life on Mars, which might be proved wrong by later evidence,” Benner said. “Scientific reputations could be too easily damaged in the process.”

In fact, Benner says that happened to one of Viking’s members — Gilbert Levin, the principal investigator of Viking’s Labeled Release experiment, who passed away in 2021.

“Gil was marginalized,” Benner said. “He was actually regarded as a crackpot by the community, even though he’s no crackpot. And at the end of the day, he’s probably going to be proven right. Or at least, at this moment, he is proven right by the preponderance of evidence.”

Levin tried for years to revive investigations into life on Mars — but it felt like the whole question had become tainted.

“That was sort of forbidden because everybody thought that the Viking mission had been a failure,” Benner said, “and therefore you shouldn’t be looking for extant life, but looking for past life.”

Almost 20 years went by after Viking before the next Mars mission, and by that time, attempts to replicate the experiments just weren’t a priority.

But that doesn’t mean progress hasn’t been made. In fact, just a few months ago, it was announced that the Perseverance — a rover that’s been exploring Mars since 2021 — had discovered a potential biosignature in Martian mudstone, which NASA has called “the closest we have ever come to discovering life on Mars.”

And all of this matters, Benner says, not only to setting the record straight, but to how we approach future Mars missions.

“All sorts of people are now talking about putting humans on Mars, and it’s quite clear that once we get humans on Mars, the problem of finding indigenous life on Mars is going to become a lot more complicated,” he said. “So we really do need to have an extant life search mission before we put humans on Mars in order to actually know the astrobiological potential. And that’s relevant for planetary protection as well for the security of the astronauts.”

Rethinking the legacy of Viking

The question of what Viking really found has been an ongoing discussion that’s been breathing new life into the mission’s legacy.

Benner is currently working on a book about the Viking and its findings, and in July, NASA is holding an event to celebrate the 50th anniversary of Viking — and maybe, Levine said, to “announce some new things about life outside the Earth; we’ll have to wait and see.”

But if you ask the people who worked on this mission its legacy extends far beyond the question of discovering evidence of life.

“From an engineering perspective, the legacy of Viking is the ingenuity and expertise of the American engineer [being] able to do a very, very complex mission because of entry, descent and landing where a thousand things have to work to within a fraction of a second,” said Levine. “So from an engineering perspective, it’s an amazing feat.”

Viking also, Levine said, “rewrote the book about planet Mars,” from its atmosphere and surface to its evolution and interior.

“And now,” he added, “we may be writing the book on the search for life outside the earth.

Nelson Freeman emphasized how Viking laid the scientific and technological foundation for future Mars missions, while keeping the public interested in the red planet, while Candy Vallado praised “the camaraderie, the feeling of purpose of collective purpose, and the way everything was executed.”

As for Rachel Tillman, she summarizes Viking’s legacy this way: “Viking was the Apollo of Mars. Viking made discoveries, such as water ice on Mars, such as the first possible indicators of biologic organics, and all of the ‘firsts’ to enable us to land on Mars for future generations, all in one mission. It was foundational and laid the groundwork for both engineering and science that is still being used today for Mars missions.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.