Delaware archaeologists find groundbreaking human remains

Eleven 17th century remains have been found in Rehoboth.

Listen 2:13Eleven individuals, whose stories have been largely unknown for centuries, will soon become a significant part of Delaware’s recorded history.

Their remains, which date back to the late 1600s, were recently discovered in the First State—and thanks to modern-day forensic anthropology, their identities will be unearthed.

The burials were found at Avery’s Rest, a 17th century plantation discovered in West Rehoboth in the 1970s. The site was originally owned by John Avery, who once served as a judge in Lewes after the colony transitioned from Dutch to English rule.

Eight of the remains are believed to be Avery and his extended family, while the other three were likely his slaves.

“It’s a juggernaut for Delaware history,” said Timothy Slavin, director of the Delaware Division of Historical & Cultural Affairs.

“It’s a brand-new chapter that opens up, it’s the potential to welcome back the 11 individuals who have been lost to history, and really, very importantly, are the three African Americans from the Rehoboth area—an area where we need to tell that story more. We’re now able to expand the story of Delaware history, and hopefully connect them to other people and tell the story of their lives.”

Avery’s Rest was discovered by state archeologists in 1976. In 2005, the Delaware Division of Historical and Cultural Affairs raised concerns about a proposed development plan in the area. The following year, the state received landowner permission to survey the site.

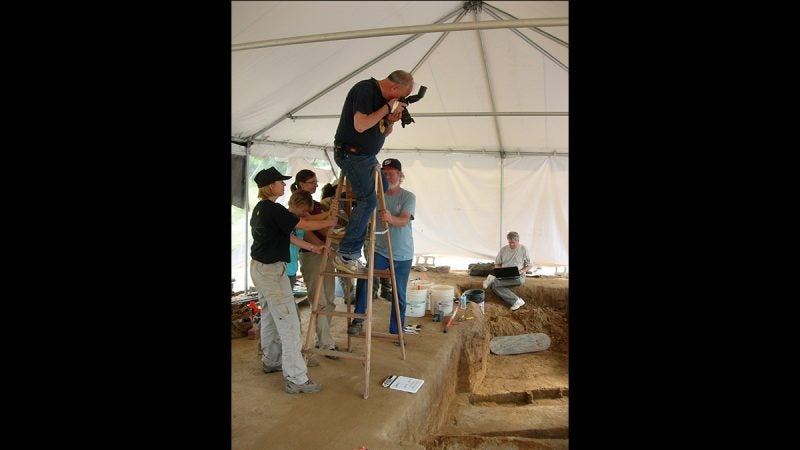

Daniel Griffith and his all-volunteer team from the Archeological Society of Delaware found the first burial in 2012 while trying to learn more about the house the Avery’s occupied between 1674 and 1682.

“It was the first opportunity in Delaware to do extensive work on what households would look like in that time period. (We tried) to find house wells, fence lines, things like that. As it turned out, in the process of doing test excavations we ran into a burial, and we went, ‘Uh oh,’” he said.

“This was totally an accident. And that’s why it’s called an unmarked burial—it’s unmarked and there are no archival records there’s burials on that location.”

After receiving permission from Avery’s descendants to dig the site, the team worked for a year before determining there were 11 burials—and that’s when they contacted the Smithsonian Institute.

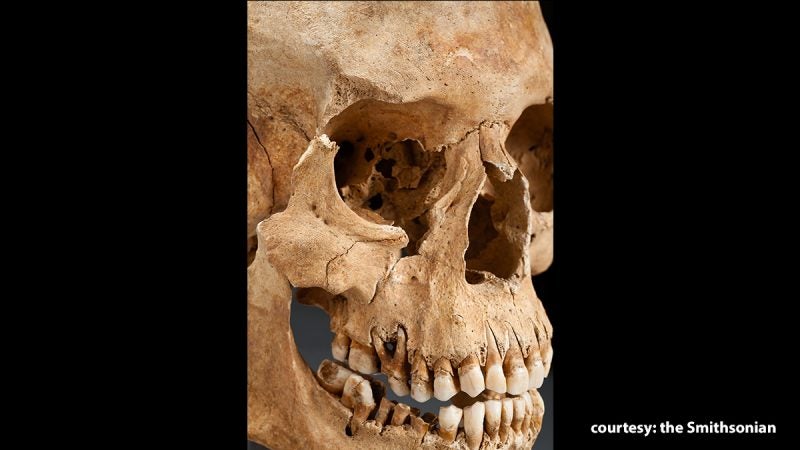

The remains were so well-preserved, forensic anthropologists are able to make conclusions about the colonists’ physical health, diet, family life and their trade.

They determined three of the remains, including a young child, were of African descent, while the others were of European descent and may be Avery, his wife, their daughters, sons-in-law and grandchildren.

The scientists believe one of the remains is Avery’s daughter Jemima’s husband, as his skull injuries indicate an altercation he was involved in that has been documented.

Among the remains were a five-month-old and a five-year-old, and the other nine individuals’ ages range from about 27 to 60.

The individuals are believed to have participated in hard labor, as indicated by arthritic changes and vertebra damage on the bones.

They also had severe tooth pathology, and almost 20 percent of their teeth at the time of death were actively abscessing. The bad teeth were likely due to a corn-based diet, which can lead to tooth decay because of the sticky carbohydrates.

However, historians and scientists also know when Avery returned to England to complete his studies he was trained as a barber surgeon. Archaeologists also found teeth that appear to have been pulled, likely by Avery himself.

Scientists also believe the family were in the business of dealing with tobacco, because all of the males have pipe stem grooves on their teeth.

“It tells us people were living here, they were not villagers, they were global people, they had traveled to the site, they had traveled away from this site, they were involved in trade and agriculture, and we’re starting to learn more about their social habits, and that will lead to a deeper and richer understanding of our Delaware history,” Slavin said.

Dr. Douglas Owsley, division head of physical anthropology at the Smithsonian Institute, has been leading the effort to learn more about the individuals. He said the discovery is the first of its kind in Delaware.

“When you’re talking 17th century sites—there’s going to be Swedish, there’s going to be Dutch—but 17th century sites are very elusive. They were here, but because of development there’s only about a dozen, and only two or three have really been fully investigated to the level we see (at Avery’s Rest),” Owsley said.

“There are no other 17th century burials that have been found in Delaware, with one exception at Bay Vista, but it was found under a road, so the remains, two adult women, are so fragmentary, it’s very hard to get any information from them. To see this kind of preservation, it’s a first for Delaware.”

Owsley, who has done extensive research on early colonial settlements at Jamestown, Va. and St. Mary’s City, Md., said the find is a significant development in the field of anthropology.

“This is so rare of a discovery in terms of preservation, in terms of the background information. You’re really dealing with frontier Delaware. These are the first wave of English settlers coming into Delaware, and on top of that you have, really, among the first Africans being brought in,” he said.

“If you put in perspective, at this time period, and the records are non-existent, at this time period of 1680, at that time there’s probably only about 50 Africans in the entire Delaware area. So, one of the things we look at is, ‘Where are they coming from?’”

Owsley said because the nature of the soil preserved the remains so well, his team is able to uncover significant genetic information.

Based on isotope data, he can conclude the three individuals of African descent were not born in Africa, but somewhere in the mid-Atlantic region, based on their drinking water.

Owsley also can conclude three of the individuals transitioned between Europe and America, based on their diets—wheat-based in Europe and corn-based in the states.

His team also can retrieve DNA, and have discovered four of the individuals have the same type of mitochondrial DNA, which will lead to more genomic information and testing.

This kind of in-depth testing that will uncover these individuals’ names has only been achievable in the last five years, Owsley said.

The remains are currently at the Smithsonian, where they are being tested for DNA and will be used to trace the genetic and anthropological history of early colonial settlers in the Chesapeake region.

“We’re getting a very personal look at the lives of these individuals. Some of these individuals nobody wrote a word about them in their lifetime,” Owsley said. “So, we’re able to get a very personal intimate look into their life, and their death as well. It’s contributing to the overall advancement of science in my field as well.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.