Battling suicides in idyllic ski towns of the West

Listen

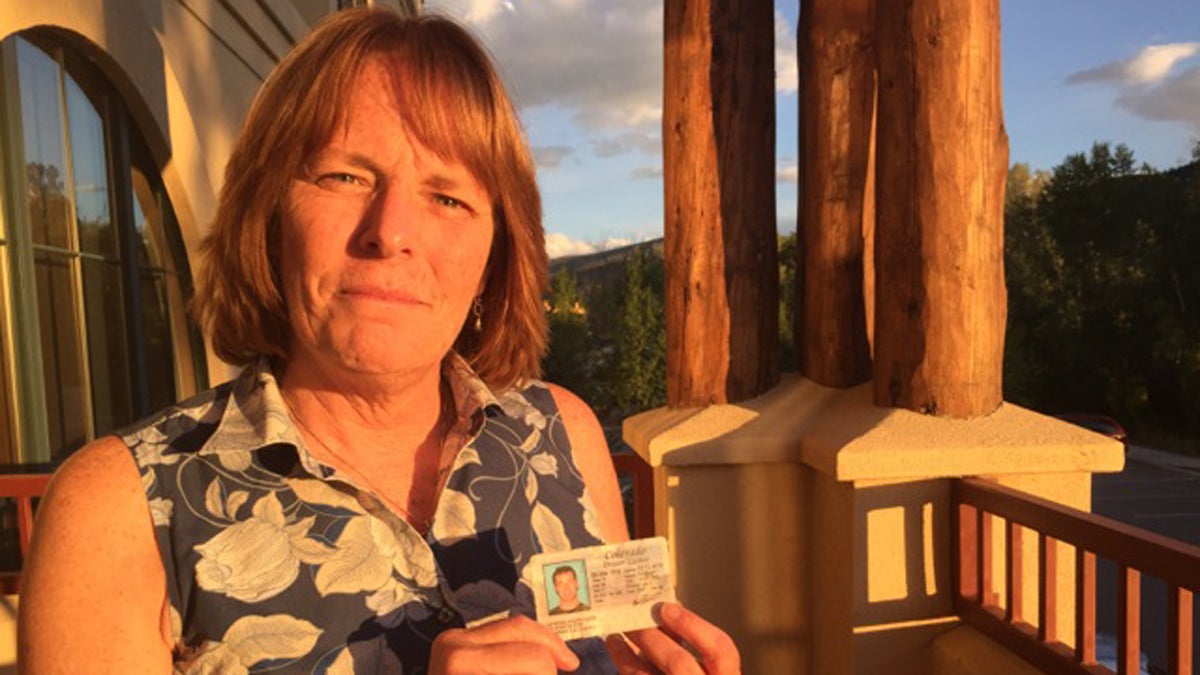

Aspen resident Kim Baillargeon holding her son Raymond Vieira's driver's license. He committed suicide in 2014. (Marci Krivonen/for The Pulse)

Idyllic ski towns like Aspen, Colorado and Jackson Hole, Wyoming may seem like heaven to some, so why do they experience higher than average numbers of suicides each year? And what can be done to reverse the trend?

With its dramatic mountain peaks, crystal clear rivers, and sunny skies, it’s hard to imagine feeling down in a place like Aspen, Colorado. And yet, residents of this opulent ski resort struggle with mental health and suicide.

Taking one’s own life is the seventh leading cause of death in Colorado, but in Pitkin County—home to Aspen—it ranks fourth. And it’s not just Aspen. The fact is, resorts around the Western United States struggle with high suicide rates, but there’s work underway to get a handle on the high numbers and help the people who need it most.

The driver’s license

Kim Baillargeon keeps her son Raymond Vieira close. She digs into her purse and pulls out his well-used driver’s license. It’s bent, and the edges are cracked.

“I keep it because it’s his personality,” Kim says. “He used to use it when he locked himself out of the house. It’s him.”

Two years ago, Raymond committed suicide at age 23.

“When the knock came on the door and I opened it, there was a sheriff and a coroner,” Baillargeon recalls. “They handed me his license and asked if this was my son. He was a 6’1″, 200-pound, green-eyed beautiful boy. His license isn’t even expired yet.”

Baillargeon is now part of a support group for people with loved ones who have taken their lives.Lifeline members meet at coffee shops, in homes and sometimes at difficult scenes where someone has taken their life. They use their personal experience to help families in the Aspen, Colorado area impacted by suicide. Lise Cohen lost her husband to suicide 13 years ago.

“It’s just very helpful to have a group of people who come in, who have walked the path and sort of know what could potentially be coming up,” she says.

The group has been busy. In the last four weeks there have been three suicides. That’s a big number for Aspen and its bedroom communities, where about 25,000 people live. Members talk about who needs help and pass around a program from a recent funeral. There are tears, hugs, and long pauses. Sadly, and surprisingly, suicide is just part of life here.

Beauty doesn’t cure pain

“I think people look at the beauty here and wonder how could anyone ever kill themselves, it’s so beautiful,” says Michelle Muething, director of the Aspen Hope Center.

The Center provides a 24-hour crisis hotline, and its clinicians are often called to the scene of a suicide to provide on-site counseling.

Sure, there’s world class skiing and five wilderness areas; people hike, fish, bike, and ski, but, Muething says, while the natural beauty may initially draw people here, reality eventually sets in. Just like the peaks they climb, the cost of living in Aspen is sky-high, and that puts financial pressure on locals.

“Many people come out here for the beauty,” says Muething. “They’ll say I vacationed here as a child, and I wanted to move back. Their recollection of a vacation is very different from an adult who has a home, works to pay a mortgage or rent, and maybe has several jobs to keep afloat.”

Substance abuse is another problem. Pitkin County has higher rates of binge and chronic drinking than the state and national averages.

“When you’re finished skiing for the day, you sit slopeside,” Muething says, describing a typical winter day in Aspen. “You have a meal and drink, and then you proceed to continue your evening into dinner, recreation, bars, so on and so forth, so it’s very much a party mentality.”

We’re not just talking about drinking. Aspen’s rate of illicit drug use is much higher, according to a state health report. Muething says the partying can lead to addiction and a downward spiral.

Colorado works to bring down suicide rate

The American Foundation for Suicide Prevention reports, on average, someone dies by suicide every eight hours in Colorado. The top eight states for the highest number of suicides are in the Western U.S., and Alaska. Sarah Brummett, Suicide Prevention Commission Coordinator with the Colorado Office of Suicide Prevention, says the cowboy culture and tough-guy mentality in the West can be problematic.

“Pulling yourself up by your bootstraps, not showing weakness—there’s the real stigma about asking someone for help, or letting them know that you might be struggling,” says Brummett. “And that’s a real barrier to people getting help.”

Rural parts of the state, like Aspen, often lack mental health services. Colorado is trying to help, spending half a million dollars in state money each year on programs to get the suicide rate down. One has gun shop owners displaying gun safety messaging in their stores. Posters suggest gun owners consider off-site storage if a loved one is suicidal. The goal of the programs is to lower the suicide rate 20 percent by 2024.

Other ski resorts struggle

Aspen isn’t alone in this challenge. The resort town Jackson Hole, Wyoming and its surrounding communities also face a high suicide rate. It’s home to a world-class ski area and about an hour’s drive from Yellowstone National Park.

“We went through a string of suicides. We had around 12 deaths in 20 months, which is a lot for the small community that we’re in,” says Adam Williamson, a licensed professional counselor who does crisis counseling in this area.

Williamson and other mental health professionals formed the Teton Valley Mental Health Coalition to identify gaps in local services. They launched ad campaigns, started a suicide survivor support group and began offering subsidized counseling. The group is tracking data to see if the number of suicides goes down.

“We’ve got a good group of people who are concerned and working on it,” says Williamson. “But, it’s just an issue everywhere, it’s a problem everywhere.”

Recently, Williamson says there has been a marked increase in the number of middle-aged men taking their lives in the area.

There is hope

Back at the meeting of the Lifeline group near Aspen, Werner Knurr is sharing his personal story of loss.

“I’m still unwilling to go to one-on-one therapy or group therapy, I don’t think it’s for everyone,” Knurr says. “I consider this group therapy,” Knurr says to the small gathering.

Two years ago this month, his son Eric took his life at age 49. Werner Knurr’s story is eerily reminiscent of Kim Baillargeon’s.

“I’ll never forget, the doorbell rang, and there was a sheriff at the door: a tall imposing man with gray hair,” Knurr recalls. “He came in and said, ‘I have some very bad news.'”

Knurr says he still asks himself what he could have done to prevent his son’s death. He has photographs of Eric up in his house.

“I don’t want to forget,” he says. “I know the wound will heal because time’s a big healer. But the scar will never go away.”

Baillargeon agrees. She tattooed her son Raymond’s name on her ankle and a symbolic semicolon on her wrist to remember him.

“When you complete a sentence or a story, you end it with a period,” she explains. “If the story’s going to keep on going, you put a semicolon. And that’s what this is about: my story isn’t going to end, and I’m not going to let Raymond’s story end either.”

She’s working with her church to reach young adults like her only son: ski resort workers mostly in their 20s who arrive in town at the beginning of the season with no friends and family nearby. She wants to connect them to the community—an effort inspired by Raymond’s death, and a way to keep his memory alive.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.