‘You better run’: After Trump’s false attacks, election workers faced threats

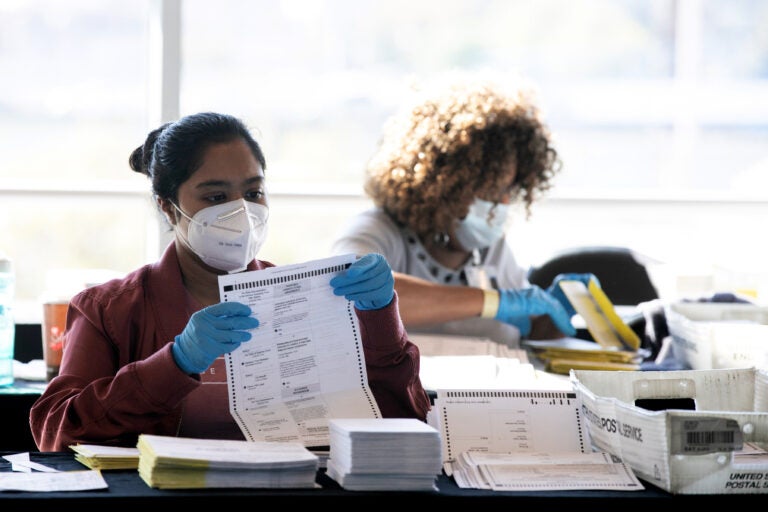

Election workers count Fulton County ballots at State Farm Arena on Nov. 4, 2020 in Atlanta. Falsehoods spread by former President Trump and his allies led to threats against election workers. (Jessica McGowan/Getty Images)

As his time in the White House came to a close, former president Donald Trump became obsessed with one office in downtown Atlanta and the workers there, making the Fulton County elections department a target of conspiracy theories and lies, which led to violent threats and intimidation.

Fulton County employees, as well as election workers around the country, are still grappling with the emotional and psychological trauma they suffered as a result of Trump’s disinformation campaign about the 2020 election, and it may have lasting consequences for recruiting and retention in the vital, but often under-appreciated field.

Online threats led to real world dangers. Law enforcement were posted outside the homes of some election officials. To feel safer, at least one official’s family moved in with in-laws. In more disturbing cases, election workers heard strangers knocking at their front doors, and menacing voices on the other end of the phone who uttered racial slurs and promised hangings.

Before Trump’s disinformation campaign began in earnest, election departments around the country were already battered as they struggled to handle the myriad repercussions of the pandemic.

In the Fulton County office, 62-year-old Beverly Walker died from the virus. Walker had worked at the county for two decades, where she had a reputation as a maternal figure, thanks in part to her goodie drawer filled with tea, coffee, and snacks.

“It was just so unexpected,” said coworker Shaye Moss, “and just so fast, and just so crazy.”

Moss took Walker’s death hard. Walker was a close friend and mentor to Moss, who invited Moss over for Thanksgiving and Christmas.

Things got more challenging for the Fulton County election team in the weeks ahead of the November election. 23 workers in the county’s warehouse tested positive for COVID-19, and the department barely got all the voting equipment delivered before the polls opened.

“We coming for you”

Trump falsely claimed victory in Georgia on election night, even though Fulton County alone had yet to count tens of thousands of mail-in ballots. Reporters and partisan observers flocked to the counting center.

With all the attention came conspiracies. Trump’s sons, Eric and Donald Jr. retweeted a 30-second video of a temp election worker in Fulton named Lawrence Sloan. In the video, a narrator falsely claimed Sloan threw away a mail-in ballot, attracting at least five million views, along with racist comments, and calls for Sloan to be identified and arrested.

Soon after Sloan saw the video and the comments, he stepped outside Fulton County’s mail-in ballot operation for a break but got scared when he saw Trump supporters protesting outside.

“Even if it’s not about me, I’m standing outside, and they know what I look like,” Sloan remembered. “Every second that goes by, more people are going to see this. Me just being here is automatically just not the best.”

He left the scene, and stayed with friends for the night, changing his appearance so he wouldn’t be recognized.

As Georgia’s recount of the presidential votes wound down, Trump and his allies focused their attacks on the Fulton County elections department, where all the staff, except for the director, are Black.

Rudy Giuliani spun a conspiracy that targeted Shaye Moss and her mother Ruby Freeman, who had helped out as a temp worker. He compared them to drug dealers.

“They should have been questioned already. Their places of work, their homes should have been searched,” he said at a virtual hearing organized by Republican state lawmakers in Georgia.

Calls came in to Moss’s old phone, which her son was using.

“He will answer it, and they’ll just call him all kinds of racial slurs, and saying what they’re going to do to him,” Moss said.

A stranger knocked on the door at Moss’s grandmother’s, where Moss used to live, and said they were there to make a citizens’ arrest. Moss’s grandma called her, frantic.

“She was just yelling on the phone, like ‘No! Stop! You cannot come in here! Stop!’ So, I just had to call the police, and this happens all the time,” Moss said.

Strangers also appeared at the home of Ruby Freeman, Moss’s mother. Pizza deliveries showed up that Freeman hadn’t ordered, and she told police she received at least 420 emails and 75 text messages, including one that read: “We know where you live, we coming to get you.”

Moss oversaw the most public part of Fulton County’s mail-in ballot operation, and she blames herself for the threats and harassment targeting her and her family.

“I’m the one that told my mom that we was hiring, we needed help. I shouldn’t have gotten my family involved at all. I should have just stayed in the office like everybody else,” Moss said. “Always just trying to help and do the most, and be available, but I’m always the one getting s****d on in the end, every time.”

Trump mentioned Freeman’s name 18 times on a now infamous call leaked to reporters, during which he pushed Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger to illegally alter the election results. The call is cited in the article of impeachment approved by the U.S. House.

“I’ll take on anybody you want with regard to Ruby Freeman, and her lovely daughter, a very lovely young lady I’m sure. But Ruby Freeman, I will take on anybody you want,” Trump said.

Fulton County’s elections director, Rick Barron, and other employees in the department were also targeted with threats and harassment. When they listened to their phone messages at work, voices called them “scumbags,” “lowlifes,” and “crooks.”

Callers pledged to shoot up the office. “I don’t know what we do these days. Is it firing squad? Is it hanging for treason,” said one anonymous caller in a message to Barron, “Boy, you better run.”

Employees spotted people taking photos of their license plates in the parking lot, and a drone flying nearby. Barron worried about his daughter’s safety.

“The people that are contacting you aren’t the people that you’re worried about, but for everyone that’s contacted you, there’s going to be some of these nuts; you’re never going to hear them coming,” Barron said.

Lasting consequences

Election workers were targeted with harassment and threats in every state won by President Biden, and in some states former President Trump won, according to Jennifer Morrell, a partner at The Elections Group, which consults with state and local election departments.

Morrell said the threats, and a feeling of helplessness in the face of disinformation, are pushing election officials to leave the field.

“People who do this job do it because they believe in it, because they have strong convictions when it comes to exercising democracy and serving,” she said, “but we’re certainly seeing an exodus.”

Morrell is especially worried election departments may struggle to recruit the thousands of low-pay temp workers necessary to pull off elections every two years if those potential workers are worried about being threatened.

“I’m horrified to think that this could be the new norm,” Morrell said. “I think it’s really important that we talk about it, and figure out how do we stamp that out.”

When Morrell talks to local election officials, she hears frustration. They tell her about politicians who are undermining the very system that put them in office, and sometimes even undermining the idea of democracy itself. Thoughts like these have been weighing on Barron especially after pro-Trump extremists stormed the U.S. Capitol.

“I don’t know if you want to call it an existential, internal crisis I’m having,” he said, “I just feel like I have a role in this that doesn’t matter anymore.”

The 2020 general elections were some of the most well run in Fulton County’s history, Barron said, but Trump and his allies made them feel like a disaster.

This story is part of a collaboration between WABE, NPR and Atlanta magazine. You can read a longer version of the story here. It was made possible with support from the Nieman Foundation for Journalism at Harvard University, and the Abrams Foundation (not affiliated with Democrat Stacey Abrams.)

9(MDAzMzI1ODY3MDEyMzkzOTE3NjIxNDg3MQ001))