The U.K. economy is growing — but its energy use is shrinking

The London skyline, shown in March 2017, is still shining bright. But the U.K. is using noticeably less energy than it did more than a decade ago. (Dan Kitwood/Getty Images)

Updated at 3:13 p.m. ET on Friday

In the global fight against climate change, the United Kingdom has quietly notched an unusual — and somewhat mystifying — victory.

For well over a decade, the country’s total energy consumption has dropped steadily. All told, there’s been a 10 percent decline since 2002, after accounting for temperature variation.

The trend is widespread, documented in the residential, commercial and industrial sectors (though not, notably, in transportation). It’s not tied to economic decline or supply shortages.

It’s also significant: The reduction in electricity use over the last decade is equivalent to shutting down the country’s largest coal- and biomass-burning power plant twice over, according to the climate policy think tank Sandbag.

And it’s unusual.

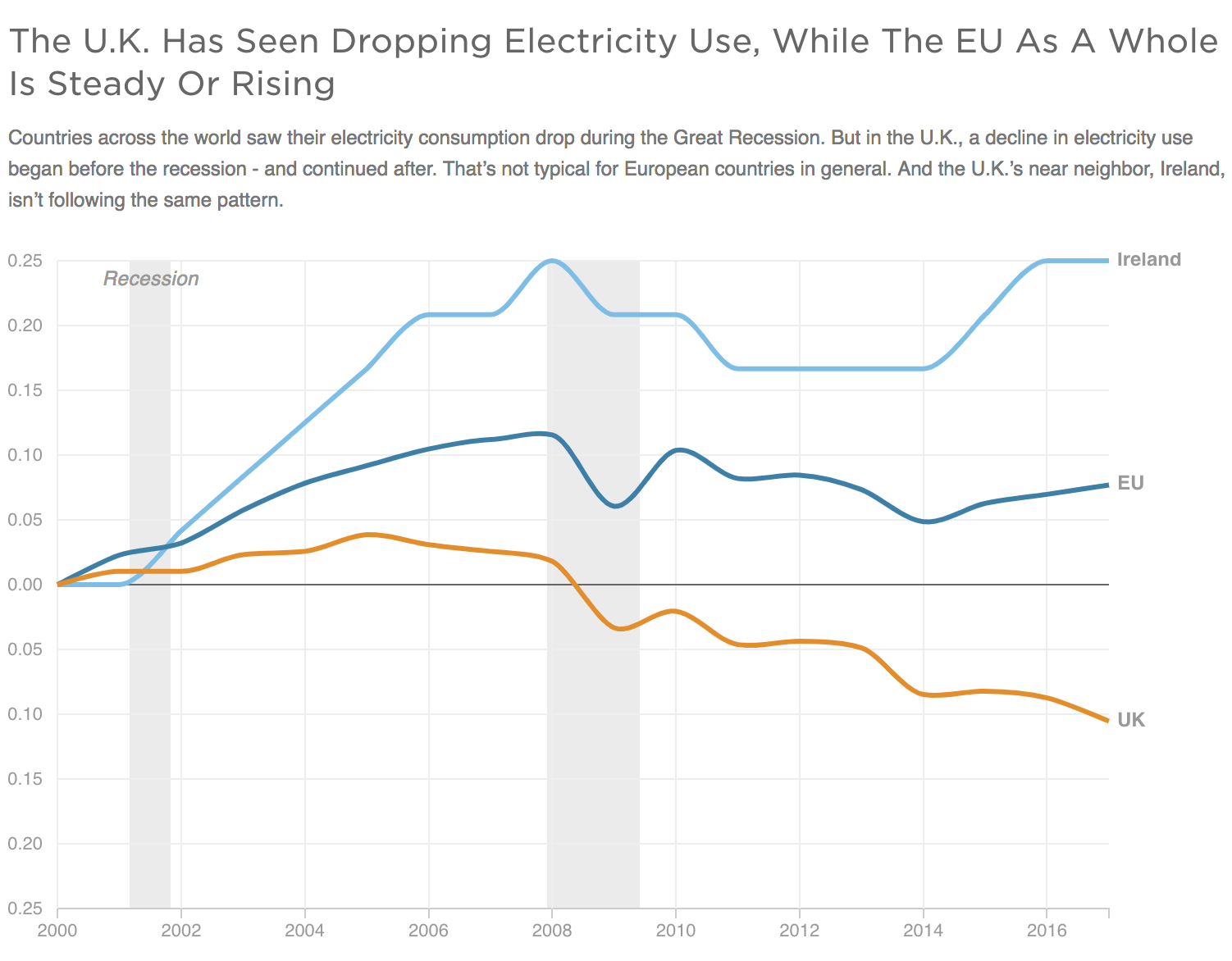

Many countries saw a dip in energy consumption during the Great Recession, but the U.K.’s dropping demand began before the crash, and has continued afterward. Other EU countries have not matched the drop; neither has the U.S., where some sectors have seen reductions in demand, but overall energy use has generally held steady.

“It’s a huge, quiet success story,” says Guy Newey, the director of strategy and performance at Energy Systems Catapult, which promotes innovation in the energy sector. He previously worked in the British government as an energy and climate adviser.

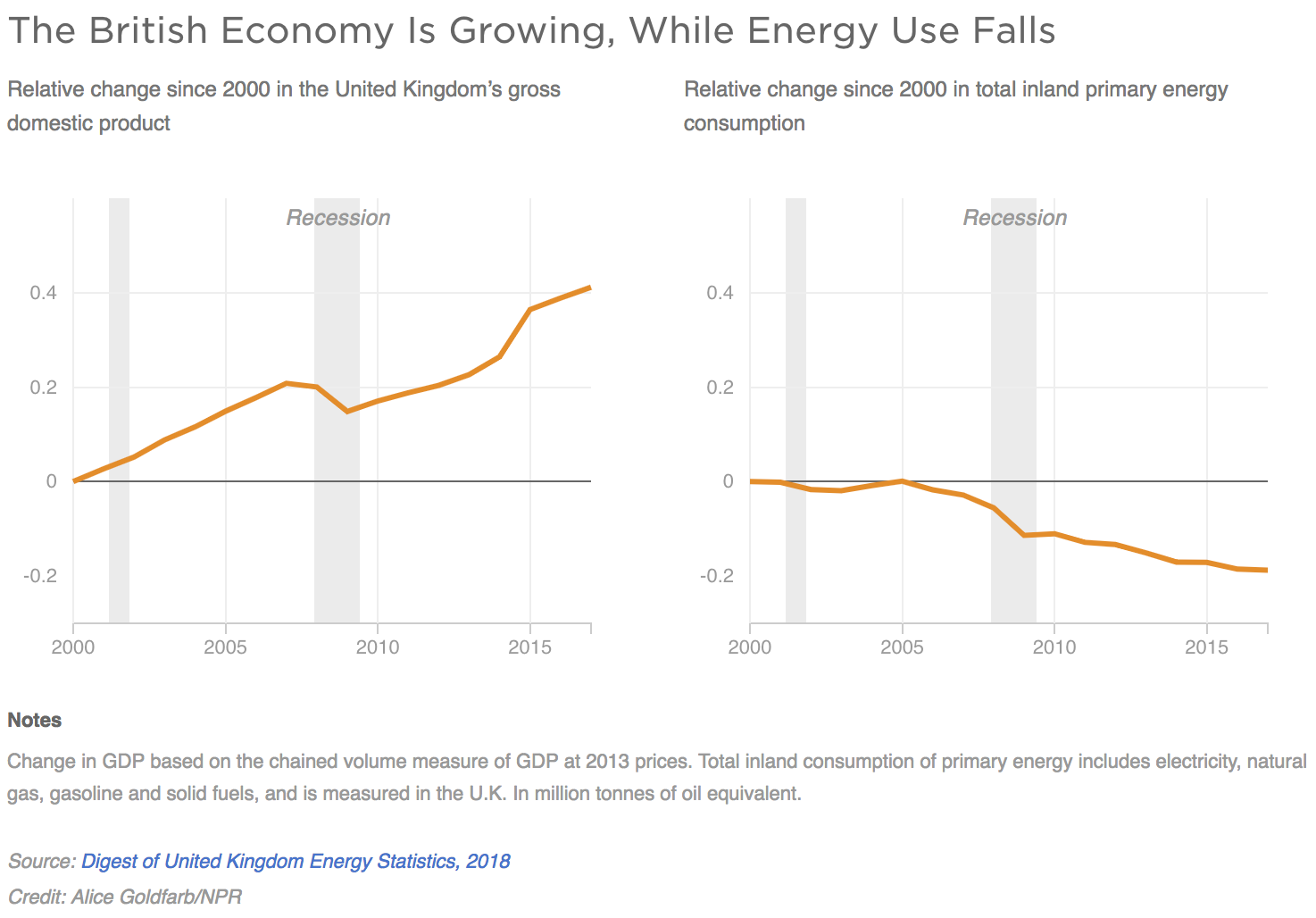

He says it’s particularly promising that the U.K.’s decline in energy consumption has continued even as its gross domestic product has risen.

“You would normally, or traditionally, expect GDP rise to be accompanied by an energy consumption rise,” he says. “That’s what you tend to see on a global level. … As people become richer, they tend to buy more stuff, use more stuff and consume more energy.”

But in the U.K., that link has been broken.

Don’t see the graphic above? Click here.

“The interesting question, for a wider global energy policy, is: ‘Can that example be replicated?’ ” Newey says.

Hypothetically, the U.K. could provide a model for other countries hoping to reduce their energy use — cutting greenhouse gas emissions — while maintaining economic growth, he says.

‘It’s a bit of a mystery’

But it would be easier to replicate if analysts could pinpoint precisely why it’s happening.

“Overall, it’s a bit of a mystery,” says Phil MacDonald, the acting managing director of Sandbag, the climate change think tank. Take the drop in electricity demand.

The U.K.’s electricity use dropped 2 percent last year, while no other country in the EU saw a decline, Sandbag found. And that drop in Britain is part of a decade-long trend.

Why? The British economy isn’t shrinking. The population is not declining. It can’t be the weather: Neighboring countries with similar recent weather patterns aren’t following suit. Ireland, for instance, is using about the same amount of overall energy as it did in 2004 — and its electricity use has risen.

It’s not skyrocketing prices, either. Analysts say British households today have, on average, similar or lower total energy costs than they had 10 years ago.

A shift away from energy-intensive heavy industry — like steel manufacturing — does account for a portion of the change, but not all of it.

LED lightbulbs and more energy efficient appliances are also contributing, but standards for lightbulbs and appliances are generally set across the EU, not just in the U.K.

Don’t see the graphic above? Click here.

But analysts can point to a few specific factors.

For reduced natural gas use, “probably the least sexy but most important change has been a quite dramatic tightening of standards for gas boilers,” Newey says. “That has been probably one of the most successful climate policies of the last 15 to 20 years.”

For electricity, MacDonald points to a push for more efficient lightbulbs in street lamps. And shifts in consumer patterns — turning off lights and dialing back thermostats — might also play a role that’s hard to quantify.

But those elements, taken together, still don’t seem to add up to a full explanation.

“It’s not perfectly understood exactly what’s happening,” Newey says.

An untold story

Efforts to tackle climate change often emphasize new, greener energy sources. But experts have long argued that it’s just as important — if not even more important — to cut down on how much energy we use.

“Reducing demand should be the primary thing you do,” says Jonathan Marshall, the head of analysis at a think tank called Energy and Climate Intelligence Unit. “It should be the lowest-hanging fruit.”

The U.K.’s success in reducing demand has not been broadly boasted about, either by the British government or climate change activists.

There are several possible reasons why. For one thing, it’s not a very sexy achievement.

“It’s a lot easier to get excited about electric vehicles and wind turbines than it is about insulation,” Marshall says.

And not all drops in demand are good, as Newey notes. “If you are really struggling with your energy bills and you sit in a cold, damp house, and it gives you health problems, that will show up as reduced energy demand. That’s not a desirable social outcome.”

That might make politicians wary of highlighting drops in demand — even though the U.K.’s drop is not tied to a recession.

Can it continue?

One key question, analysts agree, is whether the drop can be sustained over time.

In the industrial sphere, researcher Jahedul Islam Chowdhury has surveyed companies and found some aren’t investing in clean tech simply because “they don’t care about climate change,” he says.

“They said that, ‘Frankly, this is not our business,’ ” he says, paraphrasing the companies’ reactions.

But there’s some reason for optimism, as overall energy use is decreasing anyway. Government policies that offered financial incentives could inspire more companies to change course, Chowdhury argues — and he calculates industrial energy use could drop by a further 15 percent without changing output at all.

It’s a similar story in the residential sector. British homes have been using less and less energy without meaningful government intervention.

“There isn’t really a particularly strong energy efficiency policy in the U.K. at the moment,” Marshall says. The most recent push to weatherize homes was widely regarded as a failure. That suggests a renewed initiative could bring fresh reductions in demand.

There are some parallels with trends in the U.S., where per capita electricity use has been dropping. It’s not as dramatic a decline as the British have achieved, but it’s similarly happened quietly, without widespread attention.

Ellen Bell, who works for the Environmental Defense Fund on its clean energy program in the U.S., says to her, this just highlights how much possibility remains in the future.

“Things are happening without people even realizing it,” Bell says. “Imagine what we could do if we just drew the attention we needed.”

9(MDAzMzI1ODY3MDEyMzkzOTE3NjIxNDg3MQ001))