Massachusetts case probes the role schools play in teen suicide prevention

Shannon Goyette visits her son Jacob's grave in Shirley, Mass. The 16-year-old died by suicide last year. (Meredith Nierman/WGBH)

Christina worried when she found her 16-year-old boyfriend, Jacob Goyette, drunk and crying at school in the spring of 2018.

A sophomore at a suburban Massachusetts high school, Christina already knew too many people who had died by suicide. Her mind immediately went to the worst-case scenario.

So Christina says she left Jacob with a friend and headed to the social worker for help. Christina told her she was worried about Jacob’s mental health and says she was promised that word would get to his family.

But Christina says that’s not what happened. Less than two months later, she received the worst news possible: Jacob killed himself in his backyard treehouse.

“They didn’t do anything,” said Christina, who is using her middle name by request of her family to protect her privacy.

Now Jacob’s mother, Shannon Goyette, says she’s planning to sue the school district for failing to protect her son from harm. Goyette’s attorney, Jeffrey Beeler, sent a letter to the school district in September saying it is “inexcusable” that school officials didn’t notify her about Christina’s concerns.

Goyette says she didn’t know she could be any more devastated after her youngest son’s death. But she was floored to find out later that someone had tried to raise alarms that he was at risk. She believes that if she had been told, she could have saved his life. She knew that Jacob struggled with anxiety and ADHD. But she did not understand how critical the situation was.

“To have someone say to you that there was a chance we could have helped Jacob because somebody came forward on his behalf and that was a possibility we could have changed things,” Goyette said in a recent interview, alongside Christina, in her Shirley, Mass., home. “It was just devastating.”

School officials declined to discuss specifics about Jacob’s death. The social worker could not be reached for comment. But Goyette’s allegations put a focus on the responsibilities and challenges of public schools to respond to the increasing mental health needs of students.

Suicide is the second-leading cause of death for teenagers. And numbers are on the rise. More than 17,000 young people ages 9 to 18 died by suicide across the U.S. between 2008 and 2017, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. More than 17% of high school students said in a recent survey that they seriously considered suicide in the last year.

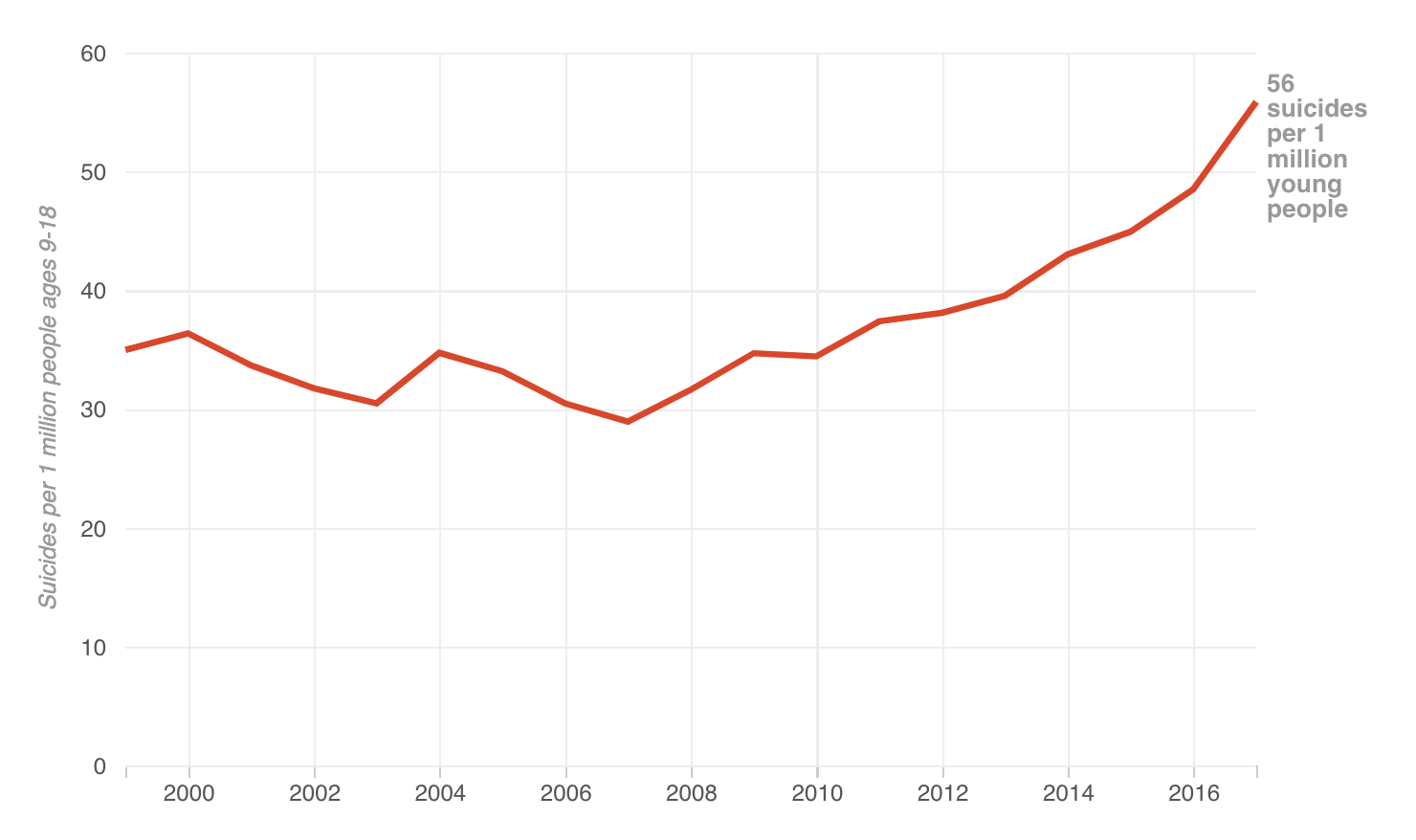

Recent Rise In Suicides Among U.S. Young Children And Teens

The rates of deaths by suicide for young people ages 9 to 18 rose from 35 per 1 million in 1999 to 56 per 1 million in 2017.

Many health experts are cautious about laying blame when tragedies occur. Seth Kleinman, a school social worker in Danvers, Mass., and an adjunct professor at Simmons University says he doesn’t have enough information to know if the social worker did anything wrong by not contacting the family. He said she should have done an assessment to determine if Jacob was in danger.

“It’s really easy in retrospect, after something terrible like this happens, to assess that she did not perform her duties effectively,” he said.

But most health specialists agree that school personnel, in contact with students for a large part of the day, can be a key resource in providing help.

“We need those adults who are around students to know what to do, to know what to hear, to know what to look for and how to adequately respond,” said Larry Berkowitz, director of the Riverside Trauma Center in Massachusetts, which provides resources to schools after a suicide, as well as suicide prevention training.

The American Foundation for Suicide Prevention recommends that states require that all public school personnel receive at least two hours of suicide awareness and prevention training each year.

Yet the foundation says only 13 states require such annual training. Most others require less frequent instruction or simply encourage staff to educate themselves.

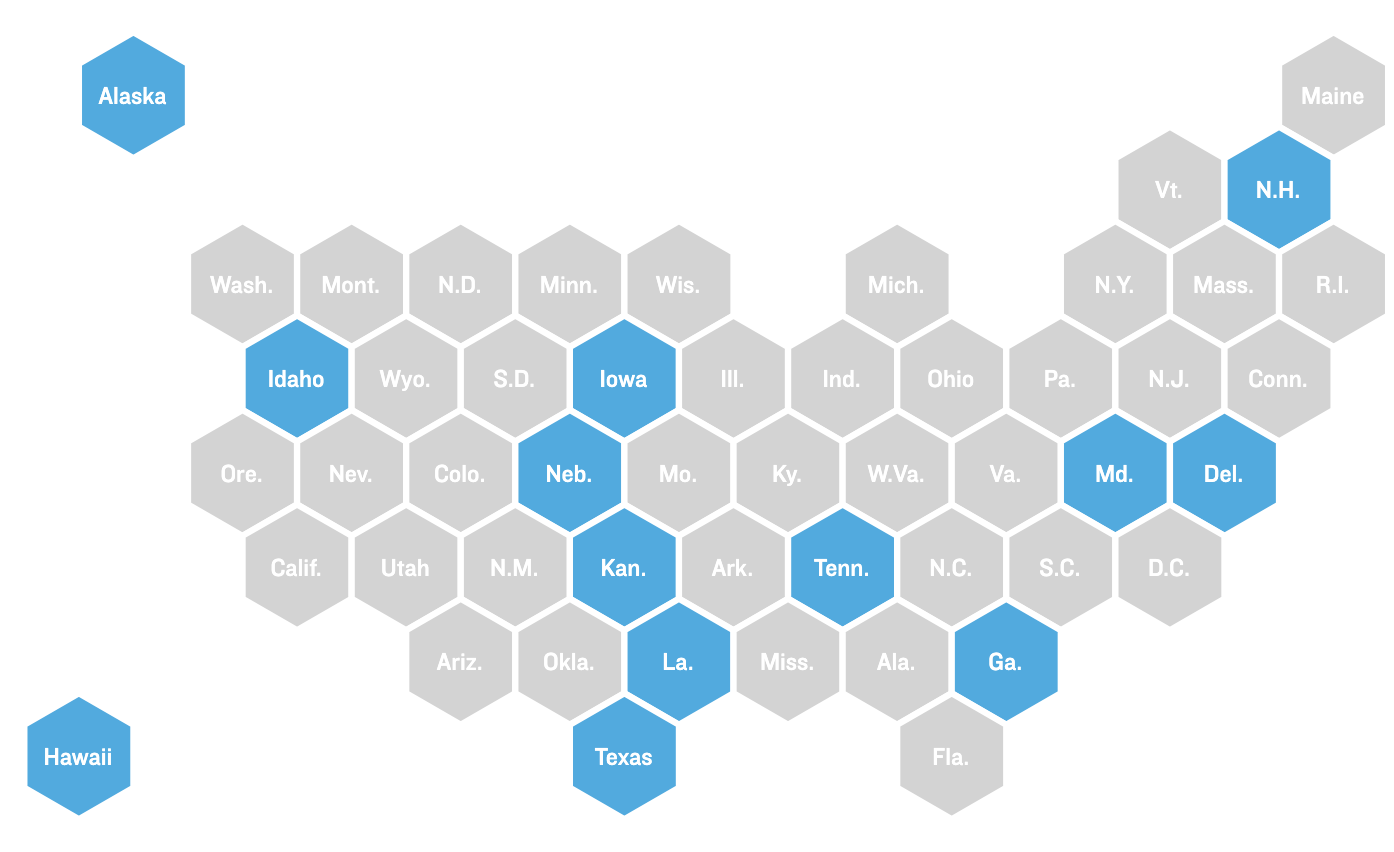

States With Mandated School Suicide Prevention Training

Only 13 states mandate annual suicide prevention training for school personnel: Alaska, Delaware, Georgia, Hawaii, Idaho, Iowa, Kansas, Louisiana, Maryland, Nebraska, New Hampshire, Tennessee and Texas.

Massachusetts passed a law in 2014 to require public schools to train staff about suicide prevention every three years. But the law was never funded, and the requirement was watered down to a guidance document. Instead, middle schools and high schools are providing a patchwork of mental health awareness and suicide prevention classes funded by government resources and private grants, some from families who’ve lost children to suicide.

Many school officials say they need more resources. In Bedford, Mass., students and faculty are still reeling from the loss of a 16-year-old student to suicide this year. Since then, the school has brought in a team from the Riverside Trauma Center to work with students and teachers affected by the loss, including a two-hour training for school personnel. Already Bedford High School Principal Heather Galante is thinking about how to fund the program every year.

“We’re seeing an uptick in concerns around anxiety and mental health,” Galante said. “Our faculty is wanting to be better prepared.”

The Acton-Boxborough Regional School District says it started providing suicide prevention training to all staff last year. A district website provides an array of resources dedicated to student mental health. Among them is information advising students to talk to a trusted adult.

Christina says she did just that, but her action went nowhere. She regrets that she didn’t contact Jacob’s family directly when she found him drinking a mixture of vodka and Gatorade out of a bottle. She says he was sobbing and wouldn’t explain why.

After Jacob’s death, Christina says she was mad at herself, mad at Jacob and mad at the school for not reaching out to the Goyettes. She dropped out of school and is working to complete high school online. She first was afraid to tell Jacob’s mother what happened. Now she wants to tell her story.

“I tried to help Jacob, but it didn’t work out,” she said, “so maybe I can help someone else.”

Jenifer McKim is a senior investigative reporter at the New England Center for Investigative Reporting at WGBH News.

If you or someone you know is having thoughts of suicide, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255) or use the Crisis Text Line by texting “Home” to 741741. More resources are available at SpeakingOfSuicide.com/resources.

9(MDAzMzI1ODY3MDEyMzkzOTE3NjIxNDg3MQ001))